Genesis Of A Holy Book

April 21, 2020 Category: Religion

A Brief Account Of Textual Clues:

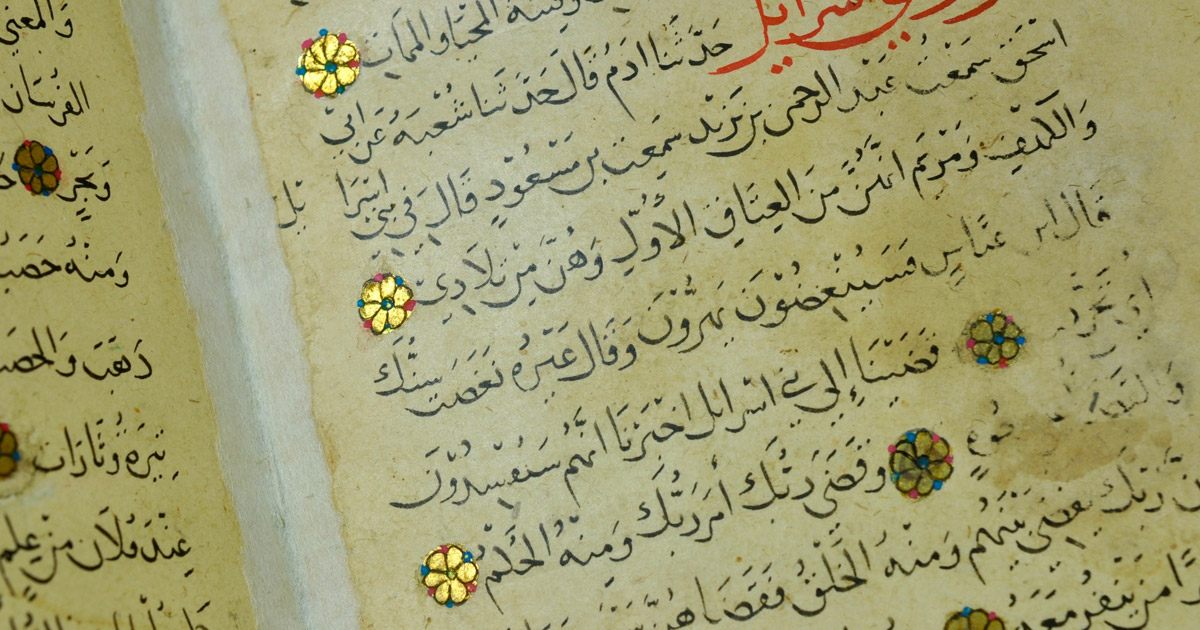

As we have seen, it was Al-Hajjaj (likely at the behest of the Umayyad Caliph, Abd al-Malik) who was responsible for much of the crafting of Koranic manuscripts–beginning in the last years of the 7th century (when the inscription on the Dome of the Rock was made)…and into the first decade of the 8th century. But the metamorphosis certainly continued long after that.

More than another century elapsed before the earliest Korans start to appear in the archeological record; affording prodigious time for extensive modifications to be made. There is no record of what might have happened in the intervening time. (For an enumeration of the first Koranic manuscripts, see my essay: “The Syriac Origins of Koranic Text”.)

It is dismaying the extent to which Islamic apologists will engage in comically outlandish rationalizations in order to square this problem with an insistence that the Koran is some kind of eternal document–the transcript of which has been unaltered since June of 632. The claim is entirely spurious. Nevertheless, it remains ubiquitous throughout the Ummah. Everyone is expected to pretend it is true.

Delusion on this matter is breathtaking to behold. Shall we simply presume that a billion people have not done their homework? {9}

The short answer is: Yes.

Such widespread ignorance–both within and outside of Dar al-Islam–can be attributed to a combination of systematic indoctrination by perfidious ulama and willful blindness on the part of sycophantic votaries. Many (ostensibly Progressive) imams are innocently oblivious; but many are most likely just lying to their congregations. {10} How, pray tell, do they manage pull this off? Programatic dissimulation.

The mendacity of fundamentalists, on the other hand, can be explained by a pathologically obstinate ideological commitment.

It is no surprise that Islamic apologists respond to critiques with by dissembling; as the alternative is to admit the preferred account of the Koran’s origins is entirely illusory. Yet there is no rejoinder the present essay; as it is merely reporting what is recounted in “sahih” Hadith collections, which are THEMSELVES centuries removed from their subject. Meanwhile, the earliest commentaries (“tafsir”) on the Koran didn’t come until the beginning of the 10th century (with Al-Tabari).

Thus far, we have been reviewing the most esteemed accounts–taken from Islam’s most trusted sources. Rather than being based on material that was written to denigrate the Koran’s legacy, the summary I have provided here is entirely based on material that would have (invariably) WHITE-WASHED the historiography.

What we have here, then, is far from a libelous historiography; it is almost certainly a romanticized version of events. For those who preserved such accounts would have REVERED both Islam’s prophet AND its holy book. Such people would have had no incentive to impugn what was their own Faith’s hallowed legacy (manuscript-eating sheep notwithstanding).

Okay, then. Enough of the historiographical record provided in the “sahih” Hadith. Let’s now explore the TEXTUAL evidence for the Koran’s dubitable history.

As we have seen, the compendium of verses that was eventually rendered Islam’s holy book came from disparate sources–originally: from “palm stalks, thin white stones, and from amongst the various reciters.” This ineluctable fact is illustrated by the disjointed nature of the text’s phraseology.

Let’s review one of the most risible examples: The case in which the putative author of the Koran (that is: the book’s protagonist; i.e. the Abrahamic deity himself) cannot even accurately quote HIMSELF. This is especially problematic considering the speaker is supposed to be omniscient (and so have a perfect memory); and his wording is supposed to always be perfect.

In the scene wherein the Abrahamic deity banishes Iblis (the fallen angel who becomes Satan) from heaven for refusing to bow to Adam, he cites himself. In 7:13, he claims to have declared: “Get down from here! It is not for you to be arrogant here. Get out; for you are the worst of creatures…You are granted respite [until Judgement Day].” However, in 15:34 and 38:77, he claims to have declared: “Be gone! You are rejected and cursed. My curse will remain upon you until the Judgement Day.”

Thus we have conflicting statements. This pertains to a statement MADE BY GOD about WHAT HE HIMSELF said. Bear in mind that this is something he would have said at a distinct point in time, so it could only have been a singular declaration.

Was god paraphrasing himself in one or both places? (This wouldn’t make sense, as the book is purportedly eternal.) The only explanation for this discrepancy is that each re-telling of the tale came from a different amanuensis–each of whom added his own special touch to the anecdote (before passing it on to the next amanuensis in the chain of narration).

To make the retellings even more problematic, Satan’s key line in this scene is ALSO quoted inconsistently. He responds in one way in 7:12 and 38:76, and in another way in 15:33. The inconsistency becomes yet more pronounced once we notice that the discrepant phrasings of the interlocutors don’t even correlate with each version of the dialogue. An indication that the Koran did not come from a single source–let alone from an infallible source–is the disparity in phrasing of statements that purport to say exactly the same thing.

Considering the “Recitations” were cobbled together in an ad hoc manner, it should come as little surprise that the final product is riddled with glaring inconsistencies. Let’s look at a few other tell-tale signs.

Note that the issue with (what eventually became) Surahs 1, 113, and 114 (along with Surahs 109 and 112) is that they were PRAYERS. In other words: They were a prescription for supplicants speaking to god; not a transcript of god speaking to supplicants. (Oops.)

When might also note the slew of mixed messages.

Those who claimed that MoM was the first prophet sent to the Arabians (28:46) seem to have forgotten that Abraham and Ishmael were supposed to have erected the Meccan cube at some point during the Bronze Age (per 2:125-129)…IN ARABIA. Those who touted 28:46 were also unaware of the verse stating that prophets had already been sent to all nations (10:47), and that Arabians had already experienced a prophet (3:183).

This is not a case of a single author who can’t seem to get his story straight. It’s what a concatenation of different narratives looks like when they are stitched together in an ad hoc manner.

Sometimes, when they were met with various accounts of a tale, amanuenses openly admitted that there were different versions…and that only god knows which is the correct one; so “don’t ask” (18:22). Recall that it was god himself that is allegedly providing the account; so this discursive shrug-of-the-shoulders is rather peculiar.

Wasn’t this meant to be a “mubeen” [clear] message? If so, mission NOT accomplished.

There also exists a conflicting message regarding the substance from which people are created. Man is formed from a blood-clot [“alaq”] (22:5, 23:14, 75:38, and 96:2), dust (3:59, 22:5, 35:11, and 40:67), the earth (11:61), clay and/or mud (6:2, 7:12, 15:26-28/33, 17:61, 23:12, 32:7, 37:11, 38:71, and 55:14), a seed (16:4), nothing (19:67 and 52:35), water (21:30), and a small amount of liquid [“nutfa”] (16:4, 22:5, 23:13, 32:8, and 76:2). This is–to put it mildly–somewhat less than perfectly clear.

Some of these pithy asseverations may have referred to the origins of HOMO SAPIENS per se, while others may have pertained to embryology. Fair enough. Yet the authors clearly hadn’t the faintest idea about biological evolution…let alone any understanding of gametes joining to produce a zygote. And they were certainly not cogent about what, exactly, they were trying to explain in each of the above verses.

Even if we discount mention of blood-clots (which can be chalked up to a comically erroneous explanation of embryo-genesis) and DESPISED FLUIDS (as in 32:8), we are treated to one or another version of biological alchemy to explain the genesis of homo sapiens. This flies in the face of the claim–repeated throughout the Koran–that god need only say “be” and it is. (Never mind any of that. Are we really supposed to DESPISE semen?)

Here are eight more contradictions that indicate disparate sources:

- The length of time it took for god to create the universe was both six days (7:54, 10:3, and 11:7) and 2+4+2 = eight days (41:9-12).

- One day for god is a thousand years (22:47) and FIFTY thousand years (70:4).

- The Earth was created before the heavens (2:29 and 41:10-12), yet the heavens were created before the Earth (79:27-30).

- Who was the first Muslim? According to the standard Islamic theology, Abraham was the first Muslim (as specified in 2:132)…though one could take Abrahamic monotheism back to Noah (or even to Adam and his son, Abel). Yet 7:143 states that Moses was the first Muslim. And 39:12 states that MoM was the first Muslim.

- Can one be forgiven for worshipping false gods? For the answer we might look to Surah 4. According to verse 153, the answer is yes. Yet according to verses 48 and 116, the answer is no.

- God pre-determines our fate in the hereafter, yet leaves it in our hands whether or not we are condemned to hellfire (see Appendix 1 of my essay on “The History Of Heaven And Hell”).

- The Final Revelation both refutes and confirms previous Abrahamic scripture (see Appendix 3 of the present essay).

- Did the Pharaoh drown or survive when attempting to traverse the parted sea? The authors seem to have been confused on this matter. (They also didn’t seem to know his name.) Only in the Koran can someone be both saved by god (10:92) and perish (72:10).

When it comes to any one of the ten cases enumerated above, one is obliged to ask: So which is it?

At best, the Koran is unclear on each of these points. Taken literally, the book contradicts itself when addressing such matters.

Upon reflection, though, there is no great mystery here. When different bits were being cobbled together, discordance was inevitable. And it isn’t very surprising that such discrepancies were not noticed; as no single “qurra” was apt to have the entire collection of “Recitations” at his disposal (to assess all the material in toto). Thus inconsistencies may not have immediately presented themselves.

And by the time people were able to perform such an assessment, the well-known verses were already thoroughly instantiated. Consequently it was too late to retract those that contradicted each another.

Such inconsistency was nothing new in scripture. The Book of Kohelet[h] ben David (a.k.a. “Ecclesiastes”) tells us that money is the answer for everything in 10:19 just after it condemns money in 5:10. Meanwhile, the 6th chapter in the first Pauline letter to Timothy of Lystra famously noted that the love of money is the root of all evil. Had Saul of Tarsus not read the 10th chapter of Ecclesiastes?

The most charitable interpretation of the text is simply that the book equivocates on such matters. We find this with, say, the admonition for either tempering one’s consumption of alcohol or forbidding it altogether. The problem even arises when it comes to the number of obligatory daily prayers (it seems to be TWO; though the relevant passages articulate it differently).

In assaying the text, it’s hard not to notice: The Koran is not a resplendent pastiche, it’s more like a hodgepodge. So over the course of a book that is supposed to be perfectly clear, we are given the impression that the identity of the first Muslim was Abraham…or Moses…or MoM. And that “shirk” is a redeemable offense…yet is also irredeemable. And that maybe wine is a good thing (but only as a deferred reward, in the afterlife). And that one should pray at the beginning and at the end of the day…but perhaps maybe more.

Again, we must ask: Is this the disquisition of a single author who can’t get his story straight? OR…is it the result of disparate sources being stitched together in a crude textual patch-work?

Things are just as problematic when it comes to questions of grave import–like whether or not there should be slavery. When it comes to clarifying such important issues, the book is delinquent. Sadly, such a stunning lack of clarity–and utter dereliction of moral intrepidity–exists for everything from freedom of speech to freedom of religion (to speak nothing of basic human rights).

The format of Islam’s holy book also reveals its worldly origins. The exposition haphazardly hops from one topic to another in what can only be described as a discursive cluster-fuck. The result is not a splendidly-woven tapestry of vignettes, it is a tohuwabohu of non-sequiturs.

Meanwhile, the book is festooned with syntactical incongruities. Once we consider the long, meandering process that eventually yielded the final product, the existence of such disjunctures makes sense.

There are various other signs of the book’s terrestrial authorship. Bizarrely, the authors instruct the audience to include the mention of certain people IN THE BOOK. (In such passages, it is often assumed the Abrahamic deity is addressing MoM personally; but this doesn’t solve the problem.) In Surah 19, we find the following instructions:

- verse 16: Also mention in the book Mary when she withdrew from her family to a place in the East.

- verse 41: Also mention in the book Abraham.

- verse 51: Also mention in the book Moses.

- verse 54: Also mention in the book Ishmael.

- verse 56: Also mention in the book Idris. {11}

And in 46:21, we read: Also mention the brother of A[a]d, when he warned his people in Al-Ahqaf [“place of the sand-dunes”]. {12}

In other words, the Koran provides advice for what to include in the Koran. Such self-referentiality would be un-necessary if we were to assume the book to be timeless. If you do not immediately recognize that this is a fatal problem, you’re not paying attention.

What is peculiar is that the Koran ITSELF refers to the Koran having been rendered piecemeal (in shreds) by those sewing dissent (15:89-91)…meaning that WITHIN the Koran is a retrospective of its own compilation (and the problems thereby encountered).

In any case, the book ITSELF is comprised of instructions to include certain things in the book; yet it never stipulates to include the INSTRUCTIONS THEMSELVES in the book. Of course, that would lead to a problem of infinite nesting; as instructions to include THOSE instructions would need to be included as well. (This amounts to the discursive equivalent of Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem, which dealt with logical systems. No system can “get outside” itself to assess itself.)

It’s not that such passages merely make it SEEM as though the Koran might be man-made; they are CONCLUSIVE EVIDENCE that the Koran is man-made. The book’s fallibility is incontrovertible. When memos to include material in a book are PART OF the book that is reputed to have been authored by god beforehand, we know we’re being taken for a ride.

An indication that some of the “Recitations” were composed long after they were mere RECITATIONS can be found in 56:77-79, which concedes that the Koran is a PHYSICAL BOOK (which, we are notified, none but the purified shall be permitted to touch). Obviously, this is not a revelation that would have been delivered so long as the Koran was a merely series of orally-transmitted verses (i.e. recitations). It is plain to see that this passage could not have been written until after the “Recitations” had been rendered as a bound volume (i.e. an actual book).

One can engage in exegetical backflips, interpreting “touch” as either “tamper with” or “apprehend” to get this directive to kinda-sorta make sense. But clearly, passages referring to the Koran as a BOOK are referring to it as a corporeal object. For 2:79 refers to “WRITING the kitab WITH THEIR OWN HANDS.” 33:6 speaks of that which is “inscribed in” the book.

Moreover, “book” (“kitab”) is distinct from “recitation” (“qur’an”), as illustrated by the opening statement of Surah 15 (which refers to Islam’s holy book as BOTH a book AND a recitation that is clear). Passages like 45:2 designate the Final Revelation as a book rather than simply a set of “recitations”. Clearly, the Koran was thought of AS A PHYSICAL BOOK…which may be recited. Also ref. 43:21 and 46:4, which inquire about other BOOKS before Islam’s holy book. Such passages were clearly not referring to mere recitations.

Indeed, the term for book (“kitab”) is the same term used for OTHER Abrahamic scripture, like the Torah. {5} Such passages were obviously not referring to material that was merely recited; they were referring to AN ACTUAL BOOK, which the audience was notified they could hold BETWEEN THEIR HANDS.

But how were the “Recitations” conceptualized by the authors? While they were (purportedly) the FINAL “revelation” [“tanzilu(n)”] from the Abrahamic deity, they were variously characterized as a “warning” [“nudhir”] and as a “reminder” [“dhikr(a)”]–as in 15:9 and 57:16. (Note that another word for “warning” / “reminder” is “threat”.)

But wait. Weren’t antecedent scriptures considered “reminders” as well? As it turns out: yes. In verses 7, 48, and 105 in Surah 21, the audience is instructed to REFER BACK to extant Abrahamic texts–which were likewise characterized as “dhikr”. In other words: The Mohammedan “Recitations” were categorized in the same way as antecedent Abrahamic revelations. The Koran, then, is yet another iteration of “dhikr”. (We promise, this is the last time!) This parity in categorization entails somewhat of a quandary. Was the Final Revelation something that re-iterated or something that transplanted?

Verses like 10:94 actually direct the audience to consult the other “people of the book” (Jews and Christians) to dispel any doubts about the verity of the “Recitations”. In other words: This Last Revelation can be validated by what was CURRENTLY AVAILABLE to the “Sahabah”: antecedent scripture that, at that point, still existed.

This brings us to another important point regarding the timeline. It is clear that all the passages that refer to Islam’s holy book as, well, a “BOOK” [“kitab”] were composed AFTER it had become a physical book (as opposed to JUST a series of orally-transmitted “recitations”, as it originally existed). Therefore, it makes no sense that these verses came from MoM’s ministry, which was exclusively oral.

In sum: The Koran is about as co-eternal with the divine as is yesterday’s gossip column. It is a historical artifact like any other ancient tract: the product of a long process of different people cobbling together choice tid-bits under different circumstances; each for his own reasons. It should not be controversial to point this out.

Islam’s holy book is the embodiment of the divine in the same way as is, say, “The Book Of Revelation” by John of Patmos. In other words: Not at all. It is eminently possible to be a Muslim and acknowledge this fact. In fact, it is the only way to be a Muslim with integrity.