Genesis Of A Holy Book

April 21, 2020 Category: Religion

The SECOND Book-burning:

Enter the chief advisor to caliph Abd al-Malik [ibn Marwan]: Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf.

Al-Hajjaj was notorious for his aggressive persecution–and mass executions–of subversives. {2} In his campaign to establish uniformity throughout the Ummah, he decided to issue his own (redacted) version of the “Recitations”: the first to include the canonical chapter / verse designations. {15} This latest revamping occurred in the first decade of the 8th century: half a century after Uthman commissioned Zayd to compile a definitive edition of the “Recitations”.

This is probably what Abd al-Malik (the caliph) was referring to when he mentioned that it was during the month of Ramadan that he had the Recitations collected. Clearly, so far as he was concerned, an acceptable version of the Koran was not established until HE commissioned it (that is: until Al-Hajjaj’s project).

And that’s not all. As the story goes, it was Al-Hajjaj who first introduced diacritical marks into the emerging Arabic script. (This claim is dubious; for at that point, the “Recitations” would have still existed in its Kufic incarnation.) Pursuant to his commissioning of this new edition, passages about which there was any disagreement were redacted. This would yield YET ANOTHER (newly approved) version.

Once again, lingering disputation was ameliorated, and any problematic passages summarily expurgated from the official record (ref. the testimony of Abd al-Masih al-Kindi, mentioned earlier).

Al-Hajjaj was especially contemptuous of any “mushaf” attributable to the oral transmission of Ibn Masoud…which would have been preserved in Kufic…and which, despite the book-burning ordered by Uthman, apparently still existed. Ibn Masoud’s influence had been severely attenuated due to the commissioning of the fabled Uthmanic Koran. So are we to believe that Ibn Masoud’s “ta’lif” had somehow survived Uthman’s manuscript purge? This may have been possible, as the “Recitations” were primarily orally transmitted (and so likely existed in memories as much as on parchments).

To recapitulate: This antipathy toward Ibn Masoud was in spite of the fact that MoM himself had proclaimed that the “Recitations” should be learned from Ibn Masoud…along with Ubay ibn Ka’ab, Mu’adh ibn Jabal, and the “freed slave of Abu Hudayfa” named “Salim” (Bukhari no. 3758 and 3806).

Clearly, the Kufic genealogy was still at issue. Al-Hajjaj decried the legacy of Ibn Masoud. “He claimed to have read the original Recitations [of god]. I swear [by god] that it is just a piece of ‘rajaz’ poetry of the Bedouins!” Al-Hajjaj considered Ibn Masoud a “takfir”; and made no secret of his disdain for this particular “qurra”–declaring that he would have “soaked the ground with his blood” had he ever met him.

Why such animosity? For reasons about which we can only speculate, Al-Hajjaj vociferously rebuked the entire Kufic legacy (of which Ibn Masoud was the preeminent figure). In doing so, it is likely he eradicated what may have remained of any record of the Final Revelation (that is: the “Recitations” as they would have existed in their original incarnation, assuming such a record existed at all).

We can be quite sure that, thereafter, no traces were left of the MoM’s preachments in their earliest form…whatever that might have been. But, of course, that’s not what the (REVISED) official record would stipulate.

Once more, the aim would have been to gloss over the shenanigans that led to the end product; not to disclose those shenanigans. (When repackaging something that is of dubious provenance, the point is to NOT show how the sausage is made.) Al-Hajjaj was no more going to announce the details of his agenda than was Uthman before him. After all, the point of obfuscation is to not keep a record of it.

Here, it helps to keep in mind that history is written by the victors. So when it came to what he did, Al-Hajjaj likely ensured that the record showed only what he wanted the record to show. After all, those who chronicled what Al-Hajjaj did WORKED FOR HIM (and the caliph). There was no independent journalism–let alone investigative journalism speaking truth to power–in the Middle Ages.

As we might expect, many were not pleased with Al-Hajjaj’s draconian project–most notably: the family of Uthman (who’s favored version was thereby rendered obsolete!) For more on this matter, refer to the testimony of Muhriz ibn Thabit (via Ibn Shabba).

In THIS edition of the “Recitations”, any passages that were inimical to Umayyad legitimacy were expunged. Al-Hajjaj’s customized “mushaf” was then declared to be the only valid Koran…and, of course, the only version that had ever existed. (Yet another reprise of: “It’s been this way all along!”)

And as with Uthman before him, Al-Hajjaj ordered the destruction of all manuscripts other than his own…which meant that by that time, there had AGAIN emerged several versions. Of course, a single version needed to be designated as definitive…lest the thread of un-impeachability be lost.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Al-Hajjaj employed the same strategy as had Uthman a generation earlier: commission a manuscript that suited those in power, and then burn everything else.

Note that the concern here was not with (IN)ACCURACY; it was with VARIATION (i.e. the existence of discrepancies). What posed problems for the community was the fact that there had AGAIN emerged numerous inconsistencies–a fact that undermined claims of inerrancy. The solution was not to investigate how this came to pass; rather it was to simply establish ONE VERSION [“ta’lif”]; and then destroy all available source material…to cover one’s tracks, as it were.

(As I discuss in my essays on the Syriac origins of the Koran: At this time, all of this material would have STILL been in Syriac.)

All this raises an interesting question: If, in those early days, the strength of the transmission of the “Recitations” lay in MEMORIZATION, then the focus on destroying MANUSCRIPTS would not have made much sense. Put another way: If extant versions existed primarily due to oral transmission, then eliminating hard copies–while undercutting an unwanted textual record–would not have solved the underlying problem. In the midst of oral tradition, folklore persists–hard copies or not.

(Don’t forget: There were well-known “qurra” who had memorized the “Recitations” during that first generation–a cadre that included men like Mu’awiya ibn Abu Sufyan and Abu Musa al-Ashari. Perhaps such oral transmission was able to circumvent even these book burnings!)

It’s actually even more complicated. Recall that Ibn Masoud and Ibn Ka’ab were not the only two men that–according to Bukhari–MoM instructed followers to treat as unimpeachable sources (re: the transmission of the “Recitations”). As mentioned earlier, this “sahih” Hadith specifies that a “freed slave of Abu Hudayfa” named “Salim” as well as a man named “Mu’adh ibn Jabal” were also approved amanuenses: designated by MoM HIMSELF (no. 3758 and 3806).

Of course, now we’re in the 8th century…long after MoM’s instructions would have been known first hand. Here, it’s worth noting that the first DOCUMENTED recounting of what MoM actually did / said was proffered by Ibn Ishaq–roughly 120 years after Mohammed’s death. However, any documents that may have been composed by Ibn Ishaq have long since been lost…and can only be referenced indirectly via redacted (read: extensively re-worked) hagiographies…the earliest of which were authored by Ibn Hisham, who died over TWO CENTURIES after MoM’s death.

Suffice to say, such a significant time-span afforded prodigious time for not insignificant modification (both witting and un-).

Moreover, Classical Arabic script was not even standardized until the early 9th century–a successor to Kufic that was fashioned as the new Faith’s liturgical language. This afforded plenty of time for extensive textual transformation (read: a slew of “honest mistakes” and deliberate alterations) to occur.

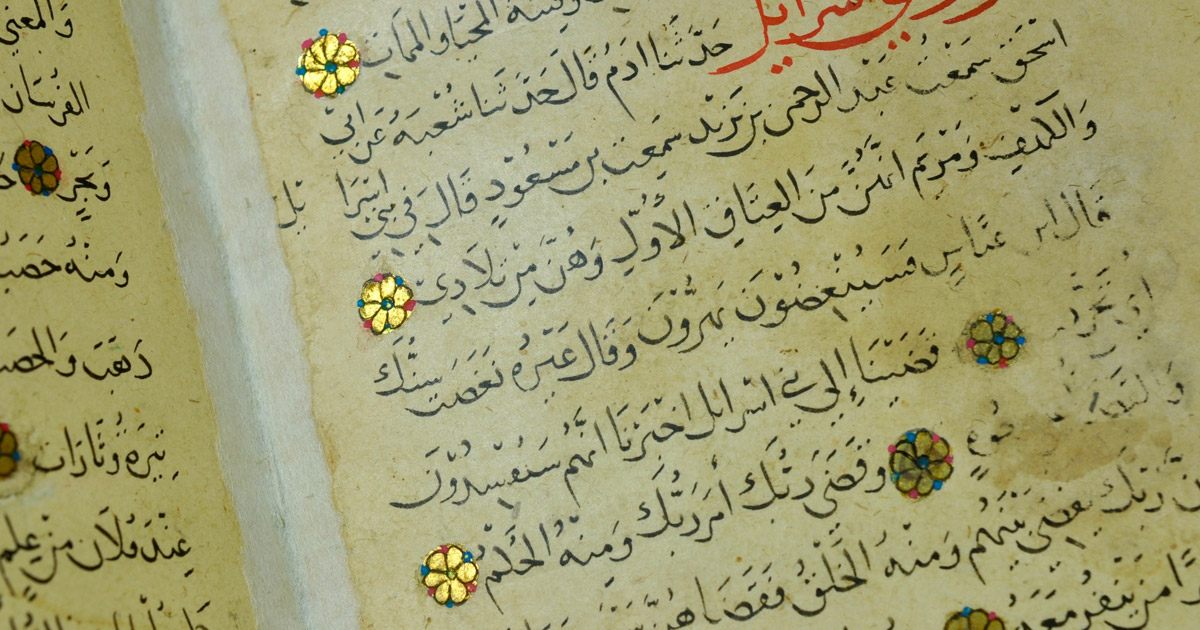

The variegation in the oldest available Koranic manuscripts indicate that there existed BOTH orthographic variants AND substantive variants–as would be expected.

Apart from some fragments that cannot be reliably dated, none of the earliest manuscripts that survived–whether in whole codices or in portions–can be dated earlier than the 8th century. This makes sense, as Uthman (in the 650’s) and then Al-Hajjaj (shortly after c. 700) had all un-approved manuscripts systematically destroyed.

And now, we don’t even have the version that Al-Hajjaj would have commissioned.