Syriac Source-Material For Islam’s Holy Book

October 18, 2019 Category: Religion

AN EXPLORATION OF EXTA-KORANIC EVIDENCE:

Evidence for the appropriation of Syriac material is not limited to Islam’s holy book. Indeed, evidence for the Syriac origins of Islamic tenets is also rife in non-Koranic material. This is exactly what we would expect if the “Recitations” were being compiled concomitantly with the rest of Islam’s scriptures. As it turns out, meta-Koranic lore is suffused with reified dogmas from antecedent Syriac lore. There are numerable examples of this. If I had to make a TOP TEN list of the most glaring, it would be as follows:

Exhibit A: The tale of the noble Assyrian vizier, Ahikar (later rendered in Arabic, “Haykar”) and his nemesis, Nadan / Nadab, was first introduced to Arabia via the (Syriac) “Me-Arath Gazze” [the aforementioned “Cave of Treasures”] by Ephrem of Nisibis in the 4th century. The apocryphal tale is a spin-off of material found in the (Judaic) “Book of Tobit”. The “Cave of Treasures” proved to be quite momentous; as its stories made their way into post-Islamic Arabian folklore. This is in large part due to the fact that it was THE ONLY work that attended to the Abrahamic genealogy from Ishmael: a key feature that made it not just appealing, but profoundly useful to the Mohammedan cause. Subsequently, the title was rendered “Ma’arah al-Kanuz” in Garshuni texts (manuscripts composed in a precursor to CA using Syriac script). Eventually, some of the material even appeared in the famed medieval anthology, “Arabian Nights” (which was not of Arabian origin, as it lifted most of its material from Persian sources). Ephrem’s work also spawned the “Conflict Of Adam And Eve With Satan”, which would later be rendered in CA; and would likewise prove to be influential in the development of Islamic lore. {24} Alas, the earliest Mohammedans assumed, wrongly, that the farcical tale of “Haykar” was an authentic part of the Abrahamic record. It wasn’t. It was a flight-of-fancy the origins of which lay with either Ephrem himself or his immediate community.

Exhibit B: The version of the parable of the “Workers In The Vineyard” found in Bukhari’s Hadith (vol. 1, no. 533; vol. 3, no. 468-471; vol. 4, no. 665) seems to have been lifted from the “memre” [homilies] of the famed Syriac writer, Narsai of Ma’alta (d. 502 A.D.) rather than from the Gospel of Matthew. The canonical (Koine Greek) version is about laborers negotiating with an employer–whereby the employer’s obligation to uphold an agreement trumps the obligation to treat people equitably. The Mohammedan version, however, is about god’s prerogative to favor those of the in-group (i.e. the pious), who are shown to be more blessed. Sure enough, that was the message conveyed by Narsai in his (Syriac) homilies.

Exhibit C: The Ishmaelite variation on the Abrahamic Faith coalesced in a memetic habitat where strident millenarianism abounded. Hence the Mohammedan creed was formulated in a climate of roiling messianic fervor. {20} Koranic eschatology is testament to this fact. The book’s emphasis on a cataclysmic End Times (replete with the literal resurrection of the dead on the Day of Judgement) was nothing new. The sensational blood-and-thunder eschaton propounded in the Koran and Hadith is attributable to the popularity of a tract known as “The Demonstrations” composed c. 337-345 by Aphrahat of Adiabene [Ashuristan]. Aphrahat was especially preoccupied with the apocalyptic “Book of Daniel”, replete with overwrought depictions of the Last Day. {21} This morbid preoccupation with cataclysmic spectacles came to undergird Mohammedan eschatology.

While the Aramaic version of the Bible (i.e. the “Harklean” redaction) included the Book of Revelation, it is important to note that the Syriac versions (the “Diatessaron” and “Peshitta”) did NOT. So the apocalyptic mayhem of the anti-Roman screed by John of Patmos (exclusively rendered in Koine Greek) would likely NOT have been the source of the Koran’s ominous depiction of the End Days. Unsurprisingly, Aphrahat’s primary source for Biblical quotations was the (Syriac) “Diatessaron”. {22} Lo and behold, the Islamic depiction of the End Times is shorn of the anti-Roman propaganda that characterized the phantasmagoric ramblings of John of Patmos; and exhibits many of the signature features of the apocalyptic-ism found in Syriac sources.

Exhibit D: The tale of Sarah being brought before a king…who is then foiled by her…and who subsequently opts to give her Hagar in her place. It seems that the Islamic version of this tale (with a few added touches, like Abraham’s three lies and the anointing of Hagar as the mother of the Ishmaelites) was likely adapted from the “Pirke” of Rabbi Eliezer (from between the 1st and 3rd century) and/or the “Book of Jasher” (from between the 3rd and 5th century) and/or the “Genesis Rabbah” (from the 4th or 5th century). To ensure that the tale had the proper Mohammedan pedigree, it was retroactively attributed to Abu Hurayrah, thereby eliding its Syriac origins.

Exhibit E: Various discrepancies occur in Mohammedan lore that ALSO occur in the Syriac Bible: the “Peshitta”. For example, the Ark of the Covenant was returned to Israel after (rather than before) Saul was anointed king. Also: Saul rather than Gideon tested his followers by having them drink from the Jordan river.

Exhibit F: The famed Syriac evangelist, Simeon Stylites, exercised profound influence on the Arabs (read: the Nabataeans) during the 5th century. Among other things, he was known for persuading Bedouins–who came to see him in large crowds–to smash their idols. This should sound familiar.

Exhibit G: The legend of “Sargis Bahira” (which was later rendered in Arabic) incorporated many of the apocalyptic themes of the aforementioned Syriac “Pseudo-Methodius” into the story of MoM’s encounter with a Syriac monk (“Bahira”) during his formative years. Most notable is the claim that this monk noticed a large birthmark on the prophet’s back; and saw it as a harbinger of prophecy-fulfillment. This anecdote was recounted in Muslim’s Hadith (no. 2344 and 2346).

Exhibit H: As mentioned earlier, the Syriac “Mor Gabriel” monastery of Tur Abdin in Nineveh (at the time, known as Oshroene) was built c. 397 at the behest of Mor Samuel. The (Syriac) legend surrounding the monastery should sound very familiar. One night, Samuel was visited by the arch-angel, Gabriel…who delivered a message from god: He was to conduct a ministry from that location.

Exhibit I: From whence did the designated year of the first revelation come? As it turned out, there was a major astronomical event that occurred in 610, tales of which made their way into Syriac and Persian folklore during the ensuing generations. The event involved what appeared to be the splitting of the crescent moon (what was, in reality, Mars appearing to break away from one end of the crescent). This was taken as an omen by the Persians, prompting a Sassanian attack on the Byzantines in Palestine.

In Islamic lore, the year occasioned an attack by those in Yemen on the Meccans…with elephants. The fabled “Battle of the Elephant” (retold as an Aksumite incursion on Mecca that occurred around the year MoM was said to have been born) was lifted from the Second Book of Maccabees, which recounted the Seleucid attack on the Levant. The Seleucids used elephants, just like their Persian forebears. Two things to note about this fabled battle, as recounted in Islamic lore:

First: There were no elephants used in the deserts of the Hijaz (for obvious reasons). The mis-casting of elephants in southern Arabia is reflected by the title of Surah 105 in the Koran—a flub that reminds us of the farce on which much of Mohammedan lore is built.

Second: The leader of the (farcical) incursion was referred to as—no kidding—“Ma-H-M-D”. (Tellingly, there was a “w” inserted between the “M” and “D”.) Note that the prefix “Ma-” (one who is) was the Semitic precursor to the Arabic “Mu-”. In the Islamic re-telling of this battle, the leader designated as “Mahamwd” was re-cast as the Sabaean leader [“negus”], Abraha. After all, he could not be referred to by the ancient Semitic moniker due to the fact that it was being re-purposed to serve as the PROPER name for the Seal of the Abrahamic prophets.

Exhibit J: Other hints of Islamic lore’s Syriac provenance include the story of “Ab-i M-L-K” and the basket of figs, which was recounted in the (Syriac) “Last Words Of Baruch” as well as in the (Syriac) “Cave Of Treasures”. (Ab-i M-L-K can mean either “father of the king” or “father is the king”; and is typically rendered “Abimelek” / “Abimelech”. It was a generic moniker for cynosures in Canaan–whether Philistine, Egyptian, Jebusite, Amorite, or Hebrew. The CA rendering would be “Abu Malek”.)

There are myriad other examples. Manuscripts of the (Syriac) “Book of Protection” include illustrations of the angel, Gabriel, on a flying white horse. In the tale of the Mi’raj (the “Night Journey” of MoM to heaven), it was MoM himself who rode the winged steed (“Buraq”); and was accompanied by “Jabril”.

All this cribbing is hard not to notice.

In addition to all this, there are various lexical clues from which we can infer Syriac origins. For example, in the Koran, Christians are referred to as “Nasara”: a variation on the Syriac “Nasraye”. There was no other language in which “Christians” were labeled in this way (i.e. as “Nazarenes”). Meanwhile, Islamic tales of spirits lurking about (“djinn”) comes from the Nabataean Syriac “ginnaye”. (I provide an extensive enumeration of the Syriac lexicon found within Islamic scripture in my essay on “The Syriac Origins Of Koranic Verse”.)

Recall that MoM (who, it cannot be reiterated enough, would have spoken a Hijazi dialect of Syriac) would not have read any of the extant source-material himself, as both he and his target audience were illiterate (a fact to which 62:2 attests). The material enumerated above would have been conveyed to him orally…IN SYRIAC. But HOW, exactly? Let’s look at the record.

Ibn Hisham’s recension of Ibn Ishaq’s biography relays the fact that MoM used to regularly go to “Marwa” (a hill on the outskirts of Mecca) and sit with a young Christian slave-boy named “Jabr”, who hailed from the Banu Hadrami (that is: from Hadhramaut in southern Arabia–a people referred to as Qahtanites in the Hebrew Bible, where both Judaism and Christianity were prevalent). {1} Ibn Ishaq himself noted that those conversations served as a primary source of MoM’s knowledge of Abrahamic lore. This fact is obliquely alluded to in the Koran (16:103).

Indeed, Islam’s holy book attests to the fact that MoM gained knowledge of Abrahamic lore from OTHER PEOPLE–namely other “People of the Book” who were relaying the tales to him orally, IN PERSON. 25:5 tells us: They say “It is just fables of the ancients, which he has had written down. They are dictated to him morning and evening.” The next verse exhorts the audience to reject this explanation, insisting instead that MoM got his information exclusively via revelation. This entreaty comes off as special pleading. We then encounter even MORE special pleading in 87:18-19. The “don’t believe the rumors; there’s nothing to see here” protestation is, to put it mildly, suspect…if not downright incriminating. As Queen Gertrude would have said, “Thou doth protest too much” (ref. Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”).

It is quite telling that the Koran pleads that it is not a rehashing of fables told by the authors’ Bedouin forebears. Moreover, the book is suspiciously adamant that its contents were not lifted from extant poetry. (The pleading is incessant. See for yourself. Refer to 6:25, 8:31, 25:4-6, 36:69, 46:17, 52:30, 68:15, 69:41, and 83:13.)

We shouldn’t be surprise, then, that it eventually came to light that some of the material was taken from the 6th-century poet, Imru al-Qays [Junduh] ibn Hujr of the Banu Kindah. Imru al-Qays was an Arab Christian who served in the court of Ghassanid prince Al-Harish ibn Jabalah; and–as it turns out–was fond of writing about the Day of Judgement. His verses were ripe for the picking; and so it went.

We might also note that the impresarios of Mohammedan lore were fans of the writings of Umaiya [alt. Umayya] ibn Abi as-Salt of Ta’if–a contemporary Qurayshi who composed poetry about Biblical legends, as recounted by Ibn Kathir. His background seems to have been of the Banu Khuza’a, who were descendants of the Azd of Ma’rib…who worshipped a Sabaean moon-god named “Al-Maqah” and made pilgrimages to his temple. As it so happened, Ta’if was a place where people worshipped “Allat”…who was considered by many to be the feminine counterpart of the Semitic god, “El” (as attested in Hismaic / Safaitic and Palmyrene / Nabataean inscriptions).

Most tellingly of all are accounts of “Bahira” (mentioned above), a Christian monk who is said to have met with the adolescent MoM; and–so the story goes–foretold of the young Qurayshi’s role in championing the Abrahamic Faith. The account of this propitious encounter is most well-known from the writings of Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari. However, it was also attested in the (Syriac) writings of John of Damascus–who, in his “Peri Ereseon” / “De Haeresibus” from the early 8th century, stated that MoM “having chanced upon the Old and New Testaments, and…having conversed with an Arian monk, devised his own heresy” (ch. 101).

Recall that Arianism was the most prominent of ANTI-Trinitarian sects; so it surely would have resonated with anyone suspicious of Nicene Christianity’s ostensive flouting of monotheism. Scholars now concur that the monk (“Bahira”) was most likely the Arian / Nestorian (read: Syriac-speaking) cleric, Sergius (who would have ALSO downplayed the divinity of Jesus of Nazareth). It is no surprise, then, that John of Damascus considered the material as heretical…even as such material would have been embraced by the nascent “Last Prophet”. The “catch”, of course, is that MoM would have had to have heard all of Sergius’ discourse IN SYRIAC; because THAT is the language that Sergius spoke. (!) For more on this, see B. Roggema’s “The legend of Sergius ‘Bahira’: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptics In Response to Islam” (2009).

Even according to the most vaunted Hadith collections (those of Bukhari and of Muslim), it is clear that Syriac Christianity–and thus the Syriac language–was not uncommon in MoM’s own tribe. The cousin of MoM’s first wife (Khadijah) was an esteemed (Syriac) Ebionite / Nestorian preacher: Waraka ibn Nawfal (ref. Ibn Ishaq’s “Sirat Rasul Allah”). Both Kadijah and MoM held Waraka in very high regard, and surely had many conversations with him. It is an odd irony, then, that–according to Mohammedan lore–it was Waraka who first persuaded MoM to embrace his role as messenger of the Abrahamic deity. (See Bukhari’s Hadith 1/1/3, 4/55/605, and 9/87/111; as well as Muslim’s Hadith vol. 1, no. 301.)

It is quite likely that Waraka exercised significant influence over MoM’s understanding of Abrahamic lore. For the aforementioned Ebionites repudiated the Trinitarian conception of the Abrahamic deity. Consequently, of all Christian accounts, the Quraysh would have likely been most familiar with polemic that inveighed against the Nicene treatment of Jesus of Nazareth: the Christology propounded by the Romans pursuant to the Council of Nicaea (and the perfidious influence of Athanasius of Alexandria). The Ebionites’ opposition to Nicene Christiantiy is attested in the “Panarion” by Epiphanius of Salamis. In fact, MoM likely would have heard NOTHING BUT denunciations of–and compelling arguments against–Trinitarian theology, and how the Roman Church’s take on Abrahamic lore was a downright scandal (to wit: patently antithetical to monotheism). Nestorianism would have therefore held some appeal—as the creed was in Syriac, and it was monophysite—a departure from the dyophysitism of the Orthodox Church (the Christianity of the Byzantines).

To reiterate: By MoM’s lifetime, Syriac proselytes had become especially disillusioned with Roman orthodoxy (esp. after the Council of Chalcedon c. 451); and likely ROUTINELY assailed it in their perorations across the Middle East, pointing out all its errancies in their liturgy. The early Mohammedans would have understood Trinitarianism to be a betrayal of the original Abrahamic theology (and, thus, antithetical to monotheism).

This is not to say that Mohammedan lore lifted ALL of its material from Syriac sources. Indeed, some tidbits came from Persian literature–as the Sassanid Empire was directly to the northeast of Arabia (and influenced Arab culture, especially via the Lakhmids of Hir[t]a). One of the most obvious examples of this is the fabled “Night Journey” of Mohammed. As mentioned earlier (but it’s worth repeating here): The “Mi’raj” was an adaptation of a fantastical tale found in the “Arda Wiraz Namag” [Book of Viraf the Just / Righteous], in which a Zoroastrian prophet (Viraf) is whisked away on a Dream Journey into the Next World, where he meets angels (e.g. Atar) and past prophets (e.g. Sraosha); and is then taken to hell to witness the torment of the damned. Finally, the prophet is notified by the godhead (Ahura Mazda) that Zoroastrianism is the one true Faith; and so the only way to salvation. The Mohammedan version of the tale is, of course, almost an exact replica of this plot-line.

It is reasonable to assume that the Sassanians promulgated the fantastical tale of Viraf, which would have been rendered in Pahlavi at the time. Several Syriac writers composed texts in both Pahlavi and Syriac; so we know there was translation between the two literatures; and thus a regular exchange of folklore. The most notable of such writers was “Mar” Aba of Asorestan (a.k.a. “Abba The Great”), who converted from Zoroastrianism to Nestorian Christianity, and traveled widely in the 6th century. (He died 28 years before MoM was said to have been born.)

Bedouin pagans of the Dark Ages appropriated antecedent deities. For example, “Azizan” / “Azizos” was the Arabian equivalent of Mars. The goddess “Dhat-Zuhran” was associated with Aphrodite (alt. the Roman goddess, Venus). Nabataean equivalents proliferated (especially in Petra): “Allat” was equated with Athena; while “Al-Uzza” was equated with Aphrodite / Venus (and was likely an analogue of the Egyptian goddess, Isis). Al-Uzza had a cubic shrine (“kaaba”) dedicated to her at Nakhla.

Either of these Arab goddesses may have been inspired by the Semitic goddess, “Elat” (consort of the Semitic godhead, “El”), who was equivalent to the Ugaritic goddess, “Atirat”. Atirat was a variation on the Akkadian goddess “Ashratu[m]”, who was herself based on the Sumerian goddess “Asherah” (consort of Anu). The Hittites called her “Asherdu[s]”. (She seems to have been conflated with the Phoenician goddess, “Ashtarte”, based on the Assyrian / Akkadian “Ishtar”, whom the Greeks called “Astarte”.) It is interesting that the authors of the “Recitations” were preoccupied with this particular goddess; as she held sway in Nabataea, and possibly as far south as the mountain village of Ta’if.

Meanwhile, “Dushara” (Romanized as “Dusares”) was seen as the equivalent of the Roman god, Zeus; and might also be understood as a Nabataean instantiation of the Sumerian god, Ninhursag. As it turns out, Dushara was the son of a (virgin) mother-goddess, who’s name was “Kaabu”. (!)

The THEME of certain deities was also recycled. The godhead of the pre-Islamic Hijazis was the moon-god, “Hubal”–probably a correlate of the Palmyrene (Syriac) moon-god, Aglibol; counterpart of the sun-god, Malak-bel. This continued a long genealogy that began with the Sumerian moon-god, Nanna…who inspired the Semitic moon-god, “Sin” (associated with the Lord of Wisdom, “En-zu”), who–it turns out–was worshipped in southern Arabia by the Qahtanites, Hadhramites / Himyarites, and Minaeans. Hence the earlier Kaaba in Yemen (see my essay: “Mecca And Its Cube”).

Hubal’s consort was the goddess “Man[aw]at”, who was worshipped by the Khazraj and the Quraysh. She was likely inspired by the Canaanite / Phoenician goddess, Asherah / Athirat / As[h]tart / Ishtar (Greek: “Astarte”); who was an analogue of the Greek goddess, Nemesis / Adrasteia. (She was alternately referred to as “Menitu” by pre-Islamic Arabians.) Allat, Al-Uzza, and Manat were considered the three “gharaniq”—as stipulated in the (rescinded) verses in chapter 53 of the Koran (since derided as the “Satanic verses”; see Appendix 5 of my essay, “Genesis Of A Holy Book”).

The preponderance of memes that the Mohammedans adopted were from Syriac Christianity; but what of Judaism’s influence? Already mentioned was material from the Targums; but there were several other instances of cultural appropriation. For example, in Islamic tradition, auspicious occasions seem to have been variations on Judaic holidays:

- Ras as-Sana (the lunar new year): from Rosh Hashanah

- Yawm Ashura (a Shiite day of remembrance): from Yom Kippur (a day of atonement)

- Laylat al-Bara’at (Night of Salvation): from Pesa[c]h (Passover)

- Eid al-Fitr (the breaking of the fast): from Serfirat ha-Omer (a harvest celebration)

Parallel practices also exist—notably: circumcision and the proscription of consuming pork. There are even some Islamic dogmas that parallel Judaic dogmas—as with the peculiar belief that the coccyx (“luz” in Hebrew; “ajbu al-thanab” in Arabic) is the anatomical origin of homo sapiens.

The appropriation of Judaica can be found in some legends about Jewish prophets that would have circulated throughout Muslim world. In “The Formation of Islam” (p. 95), Jonathan Berkey notes that “the Jewish convert, Ka’b al-Ahbar is routinely cited as [someone who is] responsible for the introduction of pious lore about the Hebrew prophets–legends that the Muslim tradition came to know as the [oft-derided] ‘Isra’iliyyat’.”

The resulting creed, then, can be accounted for by syncretism–culling material from BOTH Pahlavi sources AND Syriac sources. But wait. Would it have been possible to incorporate elements of Persian myth (Zoroastrianism) and Syriac myth (Christianity) in tandem? To answer this, we might ask: Would these cultures have intermingled in a way that may have provided readily-available source-material for the (Syriac-speaking) Mohammedans?

As it turns out: yes. For evidence of the influence of Persian lore, note the Zoroastrian apocalyptic literature that was circulating at the time–most notably the “Zand-i Wahman Yasm” (a.k.a. “Bahman Yasht”). This is further evidenced by the PAHLAVI Psalter, a book of Psalms from the 7th century that was based on the SYRIAC writings of “Mar” Aba “the Great” from the 6th century. It makes sense that Syriac-speakers of northern Arabia would have been familiar with Pahlavi, as the (Arab) Lakhmids were (Persian) Sassanid vassals…who were CHRISTIAN and who’s native language was Syriac. Indeed, the history of Syriac (i.e. Nestorian) Christianity in Persia dated back to the late 5th century, when the Sassanians permitted Babai of Seleucia [Ctesiphon] to proselytize in the the region.

Also in the 7th century (around MoM’s lifetime), the Nestorian Psalter [Book of Psalms] was composed in Syriac; and then translated by those in the region NOT into CA, but into…PAHLAVI. How long did this linguistic / memetic nexus endure? Behold the “Frahang-i Pahlavig”: a 9th-century manuscript that exhibits the intermingling of Syriac and Pahlavi. The book is effectively a Persian glossary of Syrio-Aramaic ideograms. Funny how, by that time, nobody in the region saw fit to produce such a glossary for CA!

This only makes sense if CA was not yet the lingua franca of the region. (If CA had been seen as a liturgical language, it surely would have been THE FIRST language in which important tracts would have been composed.) It seems that, at that point, there was not yet a reason to make a glossary for what would become Islam’s liturgical language. This can only be explained by the fact that it had not yet developed into a full-fledged language.

What does all this tell us? First and foremost: The literary (read: memetic) confluence of (Nestorian) Christian and (Zoroastrian) Persian lore demonstrates that memes were being transmitted (and thus translated) between Syriac and Pahlavi material during the time that the Koran–and later, Hadith–were being collated; which means that lore was also being commuted across cultures. This memetic transference also demonstrates that even as late as the 9th century, post-Islamic Persians were STILL primarily concerned with Syriac (if not Pahlavi), NOT with the newly-developed CA. Indeed, at that time, there were no equivalent glossaries for CA terms by Persians. (!) I explore the hybridization of Syriac and Persian in my essay on “The Syriac Origins Of Koranic Text”, specifically as it pertains to the portrayal of heaven in Islamic theology.

This cross-pollination of sacred lore also comports with the evidence that CA came from Syriac primarily via the Nabataeans and Tanukhids (Arabs who spoke Syriac)…and even via Lakhmid influence (as attested by Lakhmid inscriptions at Hir[t]a / Al-Hirah and Kufa). As mentioned, the Lakhmids were vassals of the (Persian) Sassanids; and so would have used some combination of Syriac and Pahlavi. So all this makes perfect sense.

Memetic facsimiles abound in sacred lore. {23} But for now, it should suffice to note that a raft of risible misconceptions proliferated around the Middle East during the Dark Ages. Such apocrypha were ubiquitous, not queer errancies propounded at the fringe. It is little wonder, then, that some of these tales made their way into the sacred scriptures of a religion that was created there. Moreover, the (re-)emergence of glaring errancies in Islamic scripture, reflecting identical errancies found in previous material, is a telltale sign that the resulting scripture was drawn from (fallible) worldly sources.

Let’s inquire further: What other Syriac sources may have provided the Ishmaelites with fodder for their new Faith? The non-canonical “Gospel of Thomas” sheds further light on the sorts of material that likely proliferated in the Middle East during Late Antiquity. As it turns out, this Gospel includes NEITHER Jesus’ crucifixion NOR his resurrection. NOR does it countenance a Christological (i.e. Pauline) conceptualization of Jesus. This turns out to be a foreshadowing of Mohammedan views. Textual analyses have revealed that this prominent “gnostic” Gospel was originally rendered in Syriac. Not coincidentally, it exhibits numerous parallels with Tatian’s (Syriac) “Diatessaron”. And some of its material even overlaps with the “Psalms of Thom[as]”, which was ALSO rendered in Syriac.

Most notable here is the “Hymn of the Pearl”–which, it so happened, also turned up in Mandaean–and even Manichaean–folklore. Mandaeans were considered “People of the Book” in the Koran; and referred to approvingly as the “Sabi’un”; alt. “Sabians”. They spoke their own dialect of Syriac–typically referred to as “Mandaic”; though they eventually adopted “Toroyo” as well. This illustrates the fact that such material was commuting from one realm of folklore (within the Syriac-speaking world) to another. And so we see that Mohammedism was not the ONLY burgeoning Faith that appropriated antecedent Syriac lore; it was happening with other burgeoning religions as well.

We find, then, that there is nothing mysterious about the regurgitation of CERTAIN PARTS of Abrahamic lore in Mohammedan lore. It is quite likely that an aspiring prophet in 7th-century Hijaz would have REGULARLY heard such material (i.e. whatever was available in Syriac) while growing up in Mecca…or in Petra…or wherever he may have lived in the region. For it was primarily in terms of the Syriac sources that Arabians first became acquainted with Judeo-Christian materials. {25} It could not have been otherwise, as SYRIAC was the language they spoke.

It’s worth bearing in mind that memetic appropriation is not unique to Islam. Cynthia Chapman (of Oberlin College) has addressed the re-purposing of ancient tales by those who wrote the Hebrew Bible. For instance, when we read in Akkadian cuneiform that the Babylonian sun-god, Shamash gave the Amorite king, Hammurabi the divine laws, we know that we have encountered a precursor to the Mosaic legend of Sinai. (For more on the incidence of divine law being handed down to prophets on mountain-tops, see part 1 of my essay on “Mythemes”.) Chapman’s insight is not earth-shattering. We find memetic appropriation in many parts of Abrahamic lore—from tales of the Flood lifted from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the tale of Moses’ beginnings lifted from the hagiography of Sargon of Akkad. So folkloric re-purposing should not come as a big surprise when it comes to Mohammedan lore.

Alas, there is an abiding reticence to attribute one’s own tradition’s (regurgitated) material to others’ material from days of old; as there is an urge to fashion it as resplendently novel. Indeed, ALL traditions are, by nature, obliged to insist: “This is not derived from exogenous sources; it is unique to us. It is therefore authentic. Consequently, it must be treated as unimpeachable.” To NOT make such an assertion is to implicitly concede that the material is, indeed, derivative; thereby bringing into question the credence of the claims being made.

The point, then, is to pass the consecrated material off as ORIGINAL, and thus as authoritative. This is all the more imperative when one is dealing with religious tenets. Admitting that key elements of a creed are derivative only serves to challenge their authenticity, thereby undermining their status as inveterate—and thus inviolable. Considering this, the staunch resistance to the elucidations in the present essay is understandable. It shatters a necessary illusion. Sanctified dogmas are thus revealed to be spurious.

To reiterate: As we assay the origins of Islamic lore, we should bear in mind that there is nothing new about adopting material from antecedent sources. We encounter the phenomenon in ALL THREE major Abrahamic religions (as well as in the minor off-shoots: Manichaeism, Sikhism, Druze, and Baha’i)—a matter that I explore at length in my essays on Mythemes.

Bottom line: Arabian bedouins (i.e. MoM’s target audience) were already familiar with Abrahamic lore by the time MoM would have undertaken his ministry; and certainly when the “Recitations” were actually composed. As F.E. Peters put it in the final remarks of his work, “Mohammed And The Origins Of Islam”: “We can only conclude that Muhammad’s audiences were not hearing these stories for the first time, as [Koran 25:5] suggests.”

Syriac sources abounded in the region during Late Antiquity. In our survey thus far, we have seen the influence of ten key figures:

- Alcibiades of Apameia and the “amora”, Shimon ben Lakish[a] of Bosra (a.k.a. “Reish Lakish”) (3rd century)

- Aphrahat of Adiabene [Ashuristan] (late 3rd / early 4th century)

- Ephrem of Nisibus [primarily associated with Edessa] (4th century)

- Epiphanius of Salamis (late 4th century)

- Narsai of Ma’alta (a.k.a. “Narses”), affiliated with the schools of Edessa and Nisibis (5th century)

- Jacob of Serug (early 6th century)

- Adi ibn Zayd of Al-Hirah; “Abraham the Great” of Kashkar; and “Babai [Aba] the Great” of Beth Zabdai [Ashuristan] (6th century)

Several other Syriac writers would have likely had an influence on the strains of Abrahamic lore that proliferated in the Middle East–consequently molding Mohammedan lore during its embryonic stages. Here are FIFTY more prominent Syriac expositors who were likely influential in the region during the relevant period:

- 1st century: Mar[a] bar Serapion of Samosata.

- Late 1st / early 2nd century: the Chaldean proselyte, “Mar” Addai of Edessa / Nisibis (a.k.a. “[Th]Addeus”); his student, Palut of Nineveh / Nisibis (a.k.a. “Mari”); and Ignatius of Antioch.

- 2nd century: the satirist, Lucian of Samosata and the neo-Platonist, Numenius of Apameia.

- Late 2nd / early 3rd century: Bar Daisan of Edessa (rendered “Bardesanes” in Latin; “Ibn Daisan” in Arabic).

- 3rd century: Saul of Samosata.

- Late 3rd / early 4th century: Jacob of Nisibis and the neo-Platonist, Iamblichus of Qinnasrin / Apameia.

- 4th century: Cyrillona of Khalkis [alt. “Kyrillos”]; Diodore of Antioch / Tarsus; the originator of monasticism at Nisibis, “Mar” Awgin of Klysma; and the founder of the Syriac library on Mount Alfaf in Nineveh, “Mar” Mattai.

- Late 4th / early 5th century: Nestorius of Germanikeia [Mar’ash] and Theodoret of Antioch / Mopsuestia.

- 5th century: Isaac of Antioch; “Mar” Theodoret of Cyrrhus; Stephan bar Sudhaile of Edessa; Ibas of Edessa; “Mar” Dadisho of Ctesiphon; Bar Sawma of Nisibis (who convened the Synod at Beth Lapat c. 484, and was affiliated with Beth Edrei on the Yarmuk River in Bashan); and Band Balai of Aleppo.

- Late 5th / early 6th century: Aksenaya [alt. “Xenaias”] of Beth Garmai (a.k.a. “Philoxenus of Mabbug”); Yohannan bar Aphtonia of Edessa; and Orthodox Christian, Simeon of Beth Arsham [Cilicia] (a.k.a. “Simeon Stylites”).

- 6th century: Severus “the Great” of Pisidia [alt. Gaza] (patriarch of Antioch); Sergius of Resh-Aina; Mshiha Zkha of Adiabene; Yakub bar Addai of Constantina [Romanized to “Jacob Baradaeus”]; Qiyore [Cyrus] of Edessa; and Yohannan of Amida (a.k.a. “John of Ephesus”).

- Late 6th / early 7th century: Paul of Tella (who composed the Syriac version of Origen’s “Hexapla” c. 617); mono-thelitist / mono-energist Patriarch, Sergios of Constantinople; “Rabban” “Mar” Hormizd of Alkosh; and Severus Sebokht of Nisibis. NOTE: All four of these men would have been contemporaries of MoM.

- 7th century: Marutha of Tagrit [Tikrit] (who was affiliated with the monastery at Beth Nuhadra, near Nineveh); Isaac of Nineveh; Abda of Hira[h]; Yuhanon III of Antioch (a.k.a. “John of the Sedre”, who was affiliated with the monastery of Eusebona); Yohannan “Saba” of Dalyatha; and Yohannan [John] bar Penkaye. {26}

- Late 7th / early 8th century: Yakub [Jacob] of Edessa; Yohannan of Damascus (a.k.a. “John Damascene”); Yohannan of Hdatta (a.k.a. “John of Daylam”); and George of the Arabs.

- 8th century: Joseph Hazzaya of Nimrud and Theophilus of Edessa.

- Late 8th / early 9th century: Timataos of Hadyab (a.k.a. “Timothy of Adiabene”) and Theodoret bar Konai of Beth Garmai [Kirkuk]. {27}

Virtually all of these men were fastidious when it came to learning the important languages of the Middle East—studying not only the precursor to their own language (Syriac), Aramaic, but the other prominent languages of the Middle East (notably: Middle Persian and Koine Greek). Yet NONE were known to have studied a language known as “Arabic”. Why not? Because such a language did not yet exist. Had CA already been established, it would have been bizarre that NONE of these men ever mentioned having to deal with it.

It’s also worth noting the Syriac writers who were prominent in the 9th century; as they would have been influential during the time the Hadith were being composed. Here are eight: Moshe [Moses] bar Kepha [Cephas] of Tagrit [Tikrit]; Dionysius of Tel Mahre; “Mar” Ishodad of Merv; John of Dara; Isho bar Nun of Nineveh; Anton [Anthony] of Tagrit [Tikrit]; Nonos of Nisibis; and Thomas of Marga (a.k.a. “the Great Zab”).

Another person of note is Sophronius of Damascus, a Syriac figure who would have been a contemporary of MoM (insofar as MoM existed). He moved to Egypt, then Constantinople, then Jerusalem, and—pursuant to his long tutelage under John Moschos of Damascus—adopted Hellenic (Byzantine) Christianity. Consequently, he learned Greek and saw things from the Chalcedonian (Orthodox Christian) point of view. Sophronius eventually became the Patriarch of Jerusalem—befriending the Saracen leader, Umar (touted as the second caliph) in the advent of the Arab (Mohammedan) conquest of Palestine. He wrote extensively on theological matters, so he gives us a window into the religious climate of the Middle East at the time. Notably, he referenced a “sacred cube” that he visited on his way to see the “Anastasis” (church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem). He was intrigued by this (rather peculiar) divine sanctuary…which he came across on a route that did NOT include the Arabian peninsula. (The sacred cube of which he spoke was likely the “Kaabu” in Petra; a matter I explore in my essay on “The Meccan Cube”.)

There are other clues pointing to the prevalence of Syriac in the region during the relevant period. The Palestinian Arian, Eusebius of Caesarea wrote his “Church History” in Koine Greek in the early 4th century; but even that was soon translated into Syriac. This would not have been done had there not been a pressing need for the work to be rendered in that particular language. (Note, there was NO OTHER language that those in the region found the need to translate it into.)

The Acts Of Thomas from the 4th century propounded the heterodox theology, Docetism, which brought into question the divinity of the person, JoN. Adherents conjectured that the Messiah’s bodily existence was mere semblance. This work was attributed to Epiphanius of Salamis; yet was later associated with “Mar” Addai (and/or his student, Mari); and seems to have originated at Edessa. Thus, the rejection of JoN as DIVINE was not unknown in the Middle East. Such arguments would have held sway over those who wanted to distance themselves from Nicene Christianity and its dubious version of monotheism.

Trinitarianism would have been inextricably linked with paganism by the Mohammedans, as there were several pre-Islamic triads in various (pagan) Arabian theologies. For example, the Qedarites in northern Arabia worshipped a moon god (Ruda), a sun god (Nuha), and a goddess associated with Venus (Atarsa-ma’in; alt. “Attar” / “Athtar[t]”). {31} Meanwhile, the Palmyrene Arabs worshipped the sky-god, Baal Shamin (their version of Hadad); the moon-god, Aglibol; and the sun-god, Malak-Bel [king-lord]. And the denizens of southern Arabia (esp. at Ma’in) worshipped a similar triad: Wadd / Sin, Yam, and Astarte. (I enumerate other pre-Islamic trinities that existed in the region in my essay, “Mythemes II”.) Considering this, it would have been surprising had there NOT been an aversion to Trinitarianism amongst (nascent) monotheists the region. For Arabs, triads were associated with pagan theology.

After The Acts Of Thomas, the use of Syriac for Abrahamic lore continued. Later in the 4th century, Frumentius of Tyre brought Christianity to the kingdom of Aksum in Abyssinia, transcribing the Bible into Ge’ez–a script that was derived from Old South Arabian. To be clear: Scribes in the region did not render the Old Testament in CA. This only makes sense if CA did not yet exist; for if it had, there would have been a pressing need for scribes to use it when circulating scripture.

It is even possible that “Against The Christians” by the 3rd-century Neoplatonist, Porphyry of Tyre was eventually translated into Syriac; especially after the book was banned–and ordered destroyed–by Emperor Theodosius II in the 5th century. By the end of the 5th century, the Nestorian proselyte, Babai of Seleucia [Ctesiphon] was convening councils in Sassanian Persia. The proceedings were conducted IN SYRIAC.

The question remains: When we consider the proselytization of these (mostly Christian) Syriac figures, what was the CONTENT? More to the point: Are there indications that what they said may have held sway during Mohammedan lore’s gestation? As we’ve seen, the answer is incontrovertible: yes. The writings of such men DID have an impact on the perceptions of impressionable Arabians as they devised their own (Ishmaelite) brand of Abrahamic Faith.

Take, for example, Saul of Samosata. He promoted the anti-Trinitarian theology that was commonly known as “monarchianism” (based on the theory of “adoptionism”). Saul was a notable figurehead in the Middle East at the time (he served as the bishop of Antioch); so it is telling that he eschewed the Trinitarian conception of the Abrahamic deity that was so emblematic of the orthodox (Pauline) version of the Faith–the version of the Faith associated with the “Rumi” (the Byzantines). Indeed, Trinitarianism was a doctrine that Saul held in utter contempt; as he deemed it a form of tri-theism, and thus antithetical to genuine monotheism. Saul was eventually deemed a heretic by the developing Church for his strident anti-Trinitarian views.

Here’s the clincher: Saul was given sanctuary by Zenobia, Arab Queen of Palmyra…in what was then the land of the Nabataeans–dubbed “Arabia Petraea” by the Romans. His hosts, the Palmyrenes, spoke a variation of Syriac; and used the (Nabataean) alphabet from which CA script was derived. His preaching surely held sway with the Levantine Arabs of the time. Surely, Saul’s polemic denouncing Trinitarianism (as inimical to the Abrahamic legacy) would have made its way around the Middle East–IN SYRIAC–by MoM’s day. This makes sense, as northern Hijazis of the 6th and 7th century were using the Nabataean alphabet…which would morph into the precursor to CA script: Kufic.

Theodore of Antioch–who served as the bishop of Mopsuestia just over a century later–had devoted his entire career to the promotion of the anti-Trinitarian doctrine. His position became known as (the aforementioned) “Arianism”. As we have seen from MoM’s own encounters, Theodore’s work ended up having profound reverberations in the region.

It is no wonder, then, that a strident repudiation of Trinitarian doctrine–and thus a rejection of the Nicene instantiation of Christology–turned out to be the focal point of the Ishmaelite movement. This is attested by the earliest surviving inscription of the new Faith: the passage found on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (purportedly made in the 690’s). The inscription is written in a proto version of the nascent liturgical language: CA.

Unsurprisingly, the same fixation (the rebuke of Trinitarianism) can be found in the Koran–most notably in 4:171 and 5:73, in which we’re told: “Say not three!” For a book that purports to be timeless, this admonition is suspicious in its specificity. Would a timeless message for all mankind (Native Americans with their totemism, Africans with their animism, Hindus with their heno-theism / polytheism, Buddhists with their pantheism, Shinto with their panentheism, et. al.) warrant such a stern rebuke of this particular point of contention?

The claim is that the Abrahamic deity’s triune nature was asserted due to a infelicitous development–whereby the “Injil” of Jesus of Nazareth had been corrupted during the intervening centuries. Said corruption, the story goes, precipitated the fraudulent Trinitarian conceptualization of the Abrahamic deity that prevailed in Rome–pursuant to the Council of Nicaea and its further promulgation by its most ardent proponent, Athanasius of Alexandria, in the 4th century. Consequently, it would have seemed to be the main point of contention for the Syriac-speaking Middle East. And so it went that, so far as many audiences were concerned, the most urgent issue to address–in all the world–was the Pauline version of Christianity…as understood through a Syriac heuristic (spec. through the filter of the Judaic Targumim and Nestorian liturgy).

It was only natural that the new Ishmaelite version of the Abrahamic Faith saw itself as a rectification of an Abrahamic tradition that had gone egregiously awry (ref. 13:38). It makes perfect sense, then, that in its earliest days, the Mohammedan movement was most fixated on THAT PARTICULAR issue: the alleged irreconcilability of a triune deity with monotheism. The suspiciously specific–one might even say monomaniacal–focus on that singular issue.

Make no mistake: The adamant repudiation of Trinitarianism that was the hallmark of the new Mohammedan movement stands to reason. Be that as it may, in doing so, its proponents could not help but co-opt elements of the extant Abrahamic lore that it found amenable…even when those elements were demonstrably erroneous. It is the skein of ERRORS (spec. those that echo signature features of Syriac material to an uncanny degree) that is most revealing.

As Mohammedan lore coalesced over the centuries, nascent apocrypha gradually accreted…and eventually calcified. Much of this was the result of the lore of one Faith (clandestinely) appropriating hand-picked lore from other Faiths. It is important to recognize that this is not uncommon. Indeed, it has occurred in many places at many times.

Case in point: The medieval Christian legend of Barlaam and Josaphat. This fanciful tale was an obvious recycling of popular stories about Siddhartha Gautama of Lumpini (a.k.a. the “Buddha”), which proliferated throughout Christendom after the Georgian monk, Euthymius of Athos lifted it from an antecedent Manichaean adaptation in the early 11th century. Such memetic recycling is a reminder that nifty motifs are regularly coopted from other cultures–something that might be called “mytheme-milking”.

One last question remains: What of Syriac writing FROM WITHIN ARABIA? As it turns out, there were several writers who hailed from the Arabian peninsula–stretching all the way to eastern Arabia (in what was known in Syriac as “Beth Qatraye” (now known as Qatar)–including Nestorian writers Dadisho, Gabriel, and Ahob from the 7th century (viz. around MoM’s lifetime). There are even legends of the apostle, Thomas, ministering as far as Suqutra (alt. “Socotra”; an Island off the coast of Yemen). This accords with the archeological record, as texts composed in (Palmyrene / Nabataean) Syriac dating from the 3rd century have been discovered there. Moreover, the aforementioned Isaac of Nineveh was born in Beth Qatraye. This means that, during MoM’s lifetime, Arabians were speaking Syriac even as far east as the Persian Gulf. (!)

It’s worth noting that Islam’s holy book was not the first mysterious tract that made its way across Arabia. The so-called “Emerald Tablet” (a.k.a. “Tabula Smaragdina”), later entitled “Kitab sirr al-Haliqa” [“Book of the Secret of Creation”], was a work of Hermetica originally composed by a writer from Anatolia: Balinas of Tyana. It dates to the early 8th century–that is: around the same time the Koran was being compiled. It was written in–you guessed it–Syriac. This is a prototypical example of supplicants trumpeting the divine origin of a book; as it was attributed (by ancient Egyptian Hermeticists of the time) to the quasi-mythical god-man “Hermes Trismegistus” of Memphis.

That this Syriac book was circulated in Arabia in the 8th century is further corroboration that SYRIAC was the lingua franca of the region; and that THAT is the language in which sacred texts of the time were composed / disseminated.

During the Middle Ages, there would be various programs of revisionist history that were implemented so as to legitimize the anti-Trinitarian theology that had come to prevail in the region (that is: the theology of the new Ishmaelite brand of Abrahamic monotheism). Part of this endeavor would surely have been the promulgation of the idea that EVERYTHING being claimed had come from “on high”–conveyed directly from the Abrahamic deity. Instead of blithely averring, “We finally figured everything out”, the bold declaration was made: “GOD HAS DELIVERED HIS FINAL REVELATION”…thereby rendering all the other material that everyone else is reading obsolete (and, by implication, their doctrines null and void).

To conclude: Once we consider the incidence of the myriad idiosyncratic tid-bits that occur in BOTH antecedent Syriac sources AND Islamic scripture, the primary source of the latter becomes quite clear. That is: By noting the slew of signature tropes AND foibles in the Koran, it is incontrovertible that much of what we find in Mohammedan lore came predominantly from Syriac source-material, which ORIGINALLY contained those same signature tropes and foibles.

Before concluding, a few last thoughts. First, we might wonder what became of the Syriac-speaking communities from which the first Mohammedans lifted their catechism? While Chaldeans (Assyrian Christians and the Oriental Churches of the East) still exist, many of the oldest communities have been lost to history…some of them quite recently. There were Jewish and Christian Syriac communities in Barwar (northern Mesopotamia) until the early 20th century. (Their demise came from the Assyrian genocide during the First World War.)

It’s also worth noting that, eventually, there WOULD be some influence from the Byzantines on the development of Islamic folklore. I explore the few linguistic influences (Greek lexemes that were adapted for CA) in my essay on “The Syriac Origins Of Koranic Text”. Some material was later inspired by Hellenic folklore—notably: The Captivity Of Dulic Ibrahim, which was simply a take-off on The Odyssey. This merely shows that cultural appropriation didn’t just magically stop after the early gestation period of Islam; and there was no cosmic law that it could ONLY come from Syriac sources.

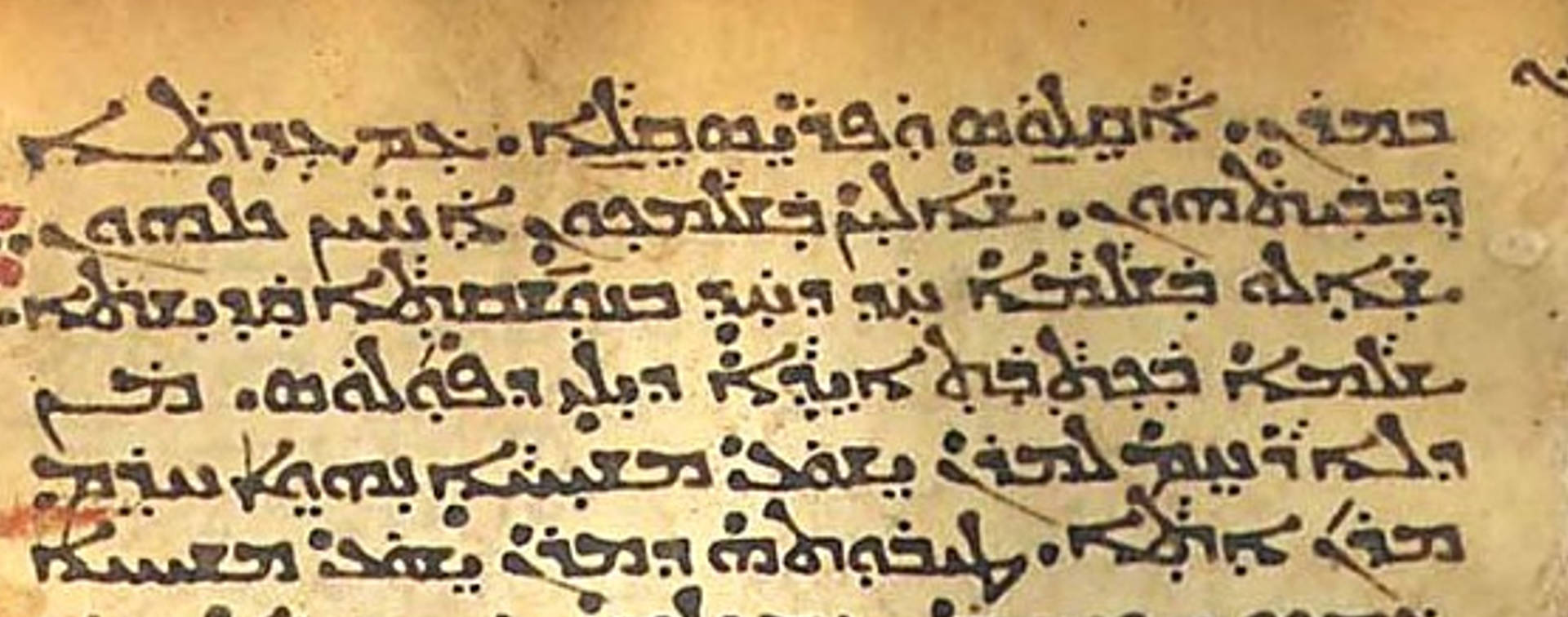

Another indication of the Koran’s Syriac origins is in the phraseology ITSELF of the text. It is this that will be explored in the “The Syriac Origins Of The Koran”, wherein I trace the development of CA vis a vis the extant language, Syriac. This will be done in order to ascertain the LINGUISTIC origins of Mohammedan lore, and of the Koran in particular.

As we’ve seen, the “Recitations” (what came to be the Koran) was originally just a bricolage of Syriac materials cobbled together as the need arose. Such materials were circulating throughout the Middle East during the relevant period, and was articulated in the lingua franca of the region. Most importantly, it served the purposes of those in power at the time.

It bears worth noting that there exists no manuscript of ANYTHING from the 7th or 8th century that was composed in CA. This should come as no surprise; as Syriac was the lingua franca of the Hijaz during MoM’s lifetime–nay of the ENTIRE REGION until the 9th century. Consequently, it is THAT material, rather than the versions found in the canonical (i.e. Koine Greek) sources, that served as grist for the newfangled (Ishmaelite) creed. In this respect, the special pleading of the Koran about itself is revealing: “Surely, [what is recounted here can be found] in the most ancient scrolls; the scrolls of Abraham and Moses” (87:18-19). This was almost certainly referring to SYRIAC sources; not to Hebrew or Koine Greek sources–a fact that is made clear by what was and was NOT incorporated into the Mohammedan liturgy.

It is clear, then, that Islam did not emerge fully-formed from MoM’s ministry. It underwent a gestation period; and existed in an embryonic form for many generations–gradually incorporating tid-bits as the occasion warranted–until the lore was formalized long after MoM’s death.

In sum: The contents of the Koran belie its purportedly preternatural nature. It was all but inevitable that confabulations–and blunders–that were unique to Syriac liturgy were the confabulations–and blunders–that would end up in Islamic scripture. The conclusion here is unavoidable: Much of what we find in Islam’s holy book points to SYRIAC sources, indicating that the “Recitations” were first spoken in that language. In my next essay, I will explore the evidence that Koranic text was, indeed, first rendered in Syriac; as CA did not yet exist.