The Syriac Origins of Koranic Text

October 26, 2019 Category: Religion

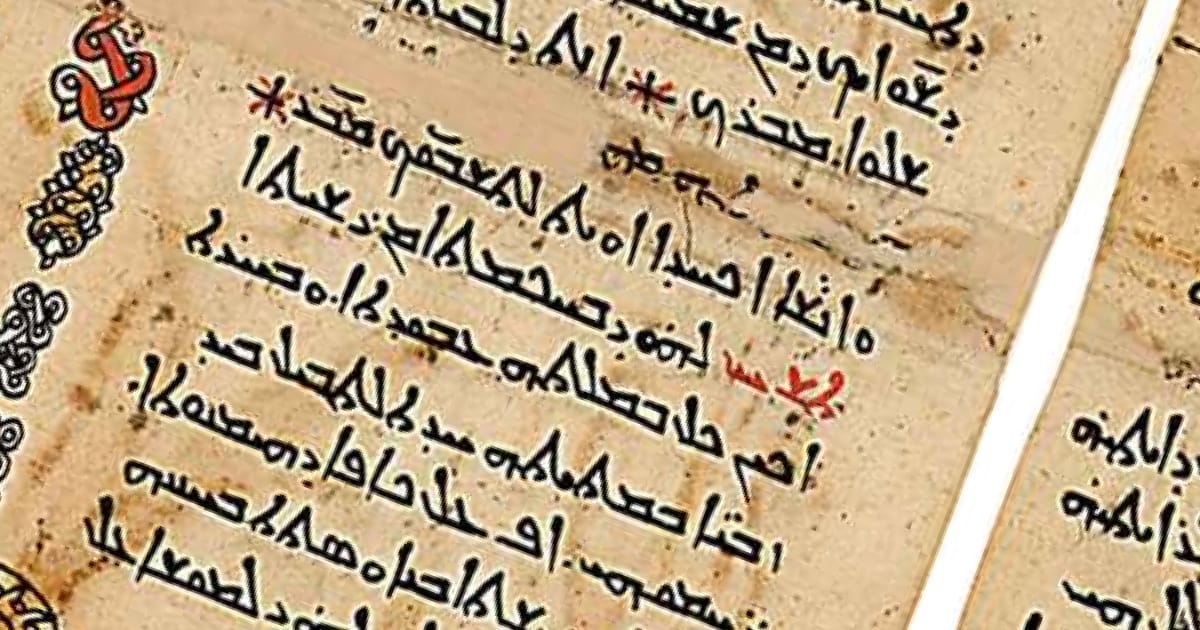

A LEXICAL ASSESSMENT:

To review: The Syriac influence emanated from “Al-Sham” (northern Levant), primarily from Edessa…and propagated down through Hauran, Nabataea, and the Nafud (northern Arabia)…into the Hijaz (western Arabia). All this occurred long before MoM’s lifetime. By the 1st century A.D., the Levantine Jewish chronicler, Yosef ben Matityahu (a.k.a. “Titus Flavius Josephus”) noted in his records that Aramaic–and its Syriac variant–was widely spoken and understood by the Parthians (Persians), Babylonians (Mesopotamians), AND the Saracens (Arabians). Indeed, even Josephus HIMSELF opted for Syrio-Aramaic instead of Hebrew, as that is what everyone was using.

During Late Antiquity, the region was primarily occupied by the Nabateans…who’s ancestors were the Lihyanites (spec. denizens of Dedan; present-day “al-Ula”). The Lihyanites used a North Arabian variant (now known as Dedanitic script), as attested at the “Umm Daraj” and “Al-Khuraybah” temples. It is interesting to note that there was a pilgrimage to these temples during Late Antiquity…and probably on into MoM’s lifetime.

Other Arab peoples included the Tanukhids (of al-Hasa; a.k.a. “Hadjar”) and Ghassanids (vassals of the Byzantines) in northwestern Arabia. Meanwhile, the Lakhmids (of al-Hirah) in northeastern Arabia were vassals of the (Persian) Sassanids, and so were also conversant in the Pahlavi (Middle Persian) of their Zoroastrian sovereigns. ALL of these peoples were Syriac-speaking. Even the Hamdanids of Al-Jazira in the 10th century were Syriac-speaking. (!)

There are also tell-tale signs of CA’s Syriac roots in etymology. Tellingly, the most distinctly Christian terms that occur in the Koran are distinctly SYRIAC terms. For example, the Syriac basis of “Rasul Allah” [Messenger of God] was the Syriac moniker, “Sheliheh d-Allaha”–as illustrated by its use in the (Syriac) “Acts of St. Thomas”.

Moreover, if we were to assume (for the sake of argument) that CA existed prior to the 8th century, we would be forced to explain the very peculiar fact that Arab communities that practiced–and proselytized–the Christian Faith never saw fit to compose any scripture in CA. It was ALL done in Syriac.

As I discussed in the previous essay (“Syriac Source-Material For Islam’s Holy Book”), by the time MoM would have lived, tidbits of Syriac lore had been circulating throughout the Middle East for many generations. It should come as little surprise, then, that myriad Syriac lexemes eventually made their way into the “Recitations”.

In other words: Distinctly Syriac terms are found in the Koranic lexicon, revealing that lexicon’s original form. Take, for instance, the term for heaven: “jannah” / “jannat”. The lexeme was from the Syriac “gannta” [garden], itself from Persian; though it is typically translated as “heaven”, as the Islamic heaven is synonymous with a cosmic seraglio–in keeping with antecedent lore.

Invariably, many words came to CA through Syriac from even earlier Semitic forms. For example, “hell” was “Ge-Hinnom” [Valley of Hinnom] in Classical Hebrew before it was rendered “Gehanna” in Syriac. It later became “Jahannam” in CA.

The most illustrative example, though, is the CA pejorative for a person who “conceals” [the truth]: “kafir”. Amongst the Ishmaelites, this term eventually came to have the connotation: one who refuses to believe. But from whence did it come? As it turns out, it derives from the Semitic root, K-F-R. Lo and behold: This was used by pre-Islamic Arabians as a term of alterity. For whom? For AGRARIANS (that is: those who were farmers as opposed to herders; which made sense, as Arabians were the latter). Thus “K-F-R” was synonymous with THE OTHER (i.e. those who covered seeds with soil when planting their crops; in contradistinction to shepherds, who did everything out in the open).

Tellingly, this disparaging term was also used for “night” (when the sun was CONCEALED), and in various other contexts besides. Sure enough, when used in the earliest verses of the Koran, the epithet “K-F-R” simply connoted those who were not within the community of believers (“Ahl al-Kitab”; People of the Book)…which was seen as simply eliding the Final Revelation. Only in later verses was such alterity equated with blasphemers / non-believers (read: those who must be FOUGHT). Unsurprisingly, a similar onomastic convention was used in Judaism during the Mishnaic era. In the Talmudic tradition, “kofe[i]r” (alt: “kefira”) was also employed as a taxonomic means of other-ization (that is: as a term of disparagement).

Other examples corroborate the present thesis. The auspicious occasion known as “Yom Ashura” [Syriac for “the Tenth Day”] retained its nomenclature even after it was adopted by the first Mohammedans, who fasted on that day in keeping with antecedent Arabian tradition. Also note that some of the appellations for the Koran’s protagonist are Syriac loan-words–as with, say, “jabbaar” [mighty / powerful] and “ra[c]hman” [merciful]. Indeed, one of the (Sabaean) deities in pre-Islamic Yemen was “Ra[c]hman[an]”.

Looking to the Koran, we find 16:103 to be a revealing comment. It states that non-believers believed that “it is only human beings who teach [Mohammed his tales of old]. The tongue of the ones to whom they refer is FOREIGN; and these Recitations are in the language of the Arabs.” This is not only an interesting accusation; it is worded in an interesting way. The language of MoM’s alleged source (for the tales of old) is clearly at issue (so far as the authors of the Koran were concerned). To whom were the complainants (those who didn’t believe MoM) supposedly referring? When they spoke of those who told MoM tales of old, THEIR language was “foreign” with respect to what, exactly? And what was the (supposed) language of the Arabs at the time (i.e. MoM’s native language)? That this matter was even brought up is rather intriguing.

The fact that language was a point of contention is somewhat of a red flag. Clearly, the language of the source-material was at issue for those who penned 16:103. We can read this as: “We, the believers (who are Arab), speak Classical Arabic; and those from whom MoM is accused of cribbing spoke something else (something that is foreign).” This all turns on what the “language of the Arabs” ACTUALLY was at any given time. Clearly, those who penned 16:103 wanted to distance themselves from their Syriac roots, so they found the need to address the matter. Hence the “everything’s been in Classical Arabic ALL ALONG” claim was established. As is often the case, the attempted cover-up ends up being incriminating.

The Nabataean lexicon offers further evidence for the roots of Mohammedan liturgy. Du-shara (“possessor of the mountain”; later rendered “Dusares” or “Orotalt”) was born of a virgin (the goddess referred to as “Kaabu”). He was the godhead worshipped at Petra and Hegra. The notion of a deified figure having been born of a virgin was surely associated with paganism. (For more examples of this, see part II of my essays on “Mythemes”.)

Before Islam, other North Arabian deities included the Assyrian moon-god, “Allah ta’ala” (Eblaite “Resheph”; Palmyrene “Arsu”; later rendered “Ruda”). Interestingly, the locutions “by Ruda” (an invocation) and “servant of Ruda” [“abd-Ruda”] (an appellation) were commonplace throughout Antiquity–especially amongst the Banu Rabi’ah ibn Sa’d. This would have given rise to similar locutions in the new Mohammedan idiom. Sure enough, that’s exactly what happened (with “bi-ism-illah” and “abd-ullah”). As Syriac morphed into CA, idiomatic expressions were retained.

Also telling are the variants of the Semitic term for “god”: “El”. The Nabatean pantheon included “Kos-allah” [Kos the god], a moniker that was based on the (much older) Edomite godhead, “Kaush”, who was–it just so happens–associated with a star and crescent moon. As mentioned in the previous essay, “Allat” was used as the female counterpart of “Allah”. And who was “Allah”? An alternate moniker for the Nabataean godhead, “Dushara”. How can we be so sure? Well, “Al-Uzza” is declared as the consort of Dushara in some places, and of “Allah” in others.

Lo and behold: All of these appellations are found in Nabataean inscriptions from Late Antiquity. (The ancient city of Hatra, in Mesopotamia, was even dubbed “Bet[h] Elaha”: Syriac for “House of God”.) This stands to reason, as the moniker “Allah” was derived from the Syriac, “eloah” / “alaha”…which was itself a variant the Aramaic “elah[a]”: a deity based on the Canaanite godhead “El”. (More on this later.)

Serendipitously, a cache of papyri discovered at Nastan (a.k.a. “Nessana”; 70 kilometers south of Gaza City), which dates from c. 674 to c. 690 (the Umayyad period), serves as a “Rosetta stone” for translation. The material is written in Greek, Latin, and Nabataean (Syriac)—as would be expected. All versions use the phrase, “In the name of the lord, the master, Jesus Christ.” The leader of the Saracens is referred to as the “amir” of the “mu-min-in” (leader of the Faithful) rather than as the “kalipha” (successor); and there is no mention of “Muslims”. The Umayyads also used Coptic and Middle Persian (in addition to Greek and their native language, Syriac). The transition to CA did not come until later. (It came with the Abbasids in the 8th century.)

So what about the use of the term “Muslim”? That ALSO did not come until later. It’s worth noting that when the Koran insists that Abraham was neither Jewish nor Christian (3:67), we are told that he was a “hanif[an] mu-s’lim[an]” (an upright person who submitted), and not a “mu-shrik-in[a]” (idolator, which seems to have been the alternative). This distinction was more descriptive than onomastic (which is simply to say that “mu-s’lim[an]” was NOT an orthonym). The idea expressed here was that the TRUE (Mohammedan) “din” dated all the way back to the early Abrahamic patriarchs. The term “Muslim” had not yet been coined as the term for a member of a distinct religion. There are only six verses in the Koran that use the locution “mu-s’lim[an]” (one who submits). The other five instances are instructive:

In 3:52, the disciples of JoN address their Messiah, saying: “We believe in god; and you are our witness that we are “mu-s’lim-un” [those who’ve submitted].” In other words, the followers of the Christ characterize themselves as “mu-s’lim-un”. (!)

In 12:101, MoM beseeches god to ensure he dies as “mu-s’liman” (one who has submitted), and is united with “salihin[a]” (the righteous). There are various terms used for those who are righteous (rightly guided)—including: salihan, hanif[a], and rashid. What’s telling is that on five occasions, the first is used in the Koran as “mu-s’lihun[a]” / “mu-s’lihin[a]” (2:11, 2:220, 7:170, 11:117, and 28:19); thus using the same nomenclature as “mu-s’lim[an]” vis a vis “[a]s’lama” / “yu-s’lim[u]”. Clearly, these were general descriptors. An illustration of this is that 3:83 tells us that all that’s in the heavens and the earth have submitted [“as’lama”] to god.

In verses 31 and 38 of Surah 27, “mu-s’limina” is used to indicate a state of submission. God insists that people come to him in such a state, which is held in contradistinction to “be against” / “resistance”.

In 33:35, we’re told about all the men who submit and all the women who submit: the “mus’limina” and “mus’limati”. Had “Muslim” been a proper noun, there would have been no need to gender the term. Clearly, it was being used as a general descriptor. In modern Arabic, the orthonym is sometimes gendered as “Muslim” and “Muslima[h]”; but that is a recent development—analogous to “Latino” and “Latina”. In CA, a term was rendered feminine by appending a “t”.)

Note that “as’lam[a]” (Arabic for “submission”, using form IV of the verbal noun) and “sala[a]m” (Arabic for “peace”) derive from the same Semitic tri-root: S-L-M—an etymological parity that leads some to conflate the two lexemes. {50} The distinction is revealed by the fact that the former is also the basis for “Islam”—a lexeme that is used ten times in the Koran. In each instance, it is clear that the lexeme means “submission”. After all, “submission” is how the prescribed “din” is characterized. (“Islam” is not used as an orthonym for a distinct religion; it is a descriptor.)

Tellingly, 3:19, 3:83, 5:3, 6:125, 39:22, and 61:7 refer to the “din” of god (rather than using the term, “Islam”). Such phrasing would not be necessary if “Islam” was a proper noun. Moreover, they state that everything in the heavens and the earth has submitted [“as’lama”] to god. (In other words, everything is prostrate to him; and everything is under his control.) God then announces that he has perfected our way of life [“din”]; and has approved of submission [“is’lama”] as that way of life. We are also told that “is’lam[u]” is the “din” that is nearest to god. Finally, we are notified that god hardens people’s hearts AGAINST submission while opening people’s hearts TO submission. At no point is it stated that the proper name of the “din” is “Islam”. And none of this has anything to do with “peace”.

Additionally, the lexeme “[a]s’lim[an]” is used for submission (to god) in 4:65, 16:28/87, and 33:22. 4:65 goes so far as to exhort us to “submit in submission” [“yu-s’lim-u ta-s’liman”]. Verses 28 and 87 of Surah 16 both refer to contrite idolators who will offer capitulation / penitence (in vain) on Judgement Day, making use of “s’lam[a]” to convey the point. And 33:22 recounts how revelation increases “iman” (faith) and “ta-s’liman” (submission, using form II of the verbal noun) within the believers.

Ergo the misnomer that “Islam” has to do with “peace” stems from a hermeneutic mis-step.

In the 1930’s, the famed Assyrian scholar, Alphonse Mingana noted that overtly Syriac lexemes in the Koran account for much of its vocabulary; and Middle Persian lexemes account for the majority of the rest. He also noted that the majority of early correspondences in Dar al-Islam were conducted IN SYRIAC—notably, the letter of a man (known as “Philoxenus”) to Abu Afr of Hir[t]a, dating from the late 7th / early 8th century. {64}

As we might expect, there are many terms in CA that reflect its lexical origins. Here are FORTY salient instances:

- “nabi” is from the Syriac “nabu”: prophet {16}

- “qiyama” is from the Syriac “qymt”: resurrection

- “furqan” is from the Syriac “purqan[a]”: salvation

- “ruh al-qudus” is from the Syriac “ruh q-d-sh”: holy spirit (“ruh” from the Syriac “ruha”, meaning breath / spirit)

- “nafs” is from the Syriac “naf[a]sh[a]”: soul (qua breath)

- “qissis” is from the Syriac “q-shysh” / “qassisa” / “qashisho”: priest

- “sadiq” is from the Syriac “z-diq”: truthful

- “muhaymin” is from the Syriac “m-hymn”: faithful

- “salih” is from the Syriac “sh-lih”: valid

- “aswar” is from the Syriac “aswar”: horseman

- “shahid” is from the Syriac “sahd”: witness

- “tanin” is from the Syriac “tannina”: dragon

- “salat” is from the Syriac “s-luta”: liturgical prayer

- “azaan” is from the Syriac “aza”: call to prayer

- “nur” is from the Syriac “naheer”: light

- “alam” is from the Syriac “alema”: world

- “jada” is from the Syriac “jada”: road

- “bayt” is from the Syriac “bayta”: house

- “suk” is from the Syriac “shekma”: market

- “qartas” is from the Syriac “khartes”: paper

- “ahmar” is from the Syriac “h-m-r”: red

- “arjuwan” is from the Syriac “argewana”: purple

- “zarkun” is from the Syriac “zargono” (alt. Persian “zargun”): gold[en]

- “quds” is from the Syriac “kudsha”: sacred

- “shamsa” is from the Syriac “shemsha”: sun

- “shirk” (idolator) is from the Syriac “sharaka”: associator (viz. god with idols)

- “buran” (ill-advised / ignorant people) is from the Syriac “bur”: ill-advised / ignorant

- “hayawa” is from the Syriac “hyut”: life

- “tufan” is from the Syriac “tupn”: flood

- “maa’a” comes from the Syriac “maya”: water

- “salaba” / “salib” from the Syriac “S-L-B[a]”: crucify / cross

- “ra’ina” from the Syriac “re’yono” / “re’yana”: shepherd

- “qusuran” from the Syriac “kusuran”: fruits reaped from being righteous

- “banat” from the Syriac “B-N-T”: daughter

- “salib” is from the Syriac “s[e]liba”: cross

- “sawm” is from the Syriac “sawma”: abstinence (viz. fasting)

- “zakat” is from the Syriac “z-kuta”: alms

- “furqan” is from the Syriac “purqana”: salvation / redemption

- “rahma[n]” is from the Syriac “rahamuta” / “ra[c]hma: mercy

- “jaddaf” from the Syriac “gaddef”: blasphemy

Meanwhile, “siraj” (star) and “saraja” (to shine) seem to come from the Syriac “shraga”. The Arabic term for worldly existence comes from the Syriac “dunya”. And “surah” (later used to designate chapters in the Koran) derives from the Syriac word for “writing”: “surta”.

The examples go on and on.

Note in this tabulation that I’m only listing lexemes with distinctly Syriac origins (ultimately from Aramaic); NOT terms that are generally Semitic (as with, say, “messia[c]h”, “nabi”, and “ab[a]” for savior, prophet, and father). Granted, “malik” is from the Syriac “malka”. But the use of “M-L-K” for a ruler goes all the way back to the Ebla-ite use of “M-L-K-M” in the 24th century B.C. Such lexemes permeate the Semitic family, so tell us little about specific etymological timelines.

We might also look to topography: “sari” for river, “sihl[a]” for stream, “tur” for mountain, and “yamm[a]” for sea: all variants of Syriac. (Not coincidentally, “Yamm” was the Canaanite god of the sea, indicating etymological origins in the Bronze Age.) The same goes for municipal terms–as with “souq” (from the Syriac “shuqa”; also used in Middle Persian) for marketplace. Also note quotidian terms like “shawb” (from the Syriac “shawba”) for heat. The Arabic term for “one of a pair” comes from the Syriac “zawga” (which was likely from the Greek “zeugos”). Also note objects like “acorn”: the Arabic “ballut” is from the Syriac “ballota”; as the oak tree played a prominent role in Palestinian lore. (For other examples, see “Studies In The Grammar And Lexicon Of Neo-Aramaic” ed. Geoffrey Khan and Paul M. Noorlander.) Prepositions in CA are also from Syriac–as with “min” (from “men”) meaning “from”.

There are other indications that Mohammedans culled their lore from Syriac sources. For “messenger”, “rasul” was used instead of a derivative of the Greek “apostolos” (one who is sent). As it turns out, this moniker is derived from the Syriac “r-s[h]-l” (to give way). And what of the appellation “rasul Allah”? As it turns out, the Syriac term for “messenger of God” (“sheliheh d-Allaha”) had been used throughout the “Acts of Thomas”. For those seeking an alternative to the “son of god” trope, this would have been the go-to phrase.

As mentioned earlier, an alternate variant, “sheliheh” (messenger) was used throughout the Syriac “Acts of Thomas”, which was circulating throughout the region during Islam’s gestation period. (The Hebraic “sheliah” is yet another variant.)

Meanwhile, “kalimatuhu” [his word] is used for god’s “word” instead of the Greek “logos”. That is derived from the Syriac “k-l-m[a] thu” [his voice].

Some common verbs in CA exhibit vestiges of their Syriac origins–as with:

- “dagash” (from the Syriac “d-gash”) meaning “to show”

- “nadar” (from the Syriac “n-tar”) meaning “to watch over”

- “faram” (from the Syriac “p-ram”) meaning “to cut”

Even “qur’an” (which is merely a variation on the CA term for “reading” / “recitation”, “qara’a[t]”) is derived from the Aramaic term for liturgical readings: “qryn[a]” (alt. “qeryana” / “qiriana”). During Late Antiquity, this was also used by Syriac speakers to refer to a sacred book (i.e. a lectionary). And, as mentioned earlier, the term for chapters IN that book was “s[h]era”, which came from “surta”: the basis for the Arabic “sura”. It’s also worth nothing that K-R-N-a has the same Semitic basis as “Mikra”—the Aramaic name of the Hebrew Bible.

What about the word for BOOK? Sure enough, “kitab” is from the Syriac “k-tobo”. (Also note the Syriac lexeme, “asfar”.) This makes sense, as “K-T-B” was the Old Semitic root for “writing”. As it so happened, “Kutba[y]” was the Nabataean god of scribes. His consort was none other than the Arabian goddess, “al-Uzza” [Syriac: “Uzzay”]…who was worshipped by Hijazis during MoM’s lifetime (an Arabian shrine existed for her at Nakhla).

What about the term used for the new religion? Lo and behold: “Islam” is a variation on the Arabic term from submission, “aslam”…which is derived from the Syriac verb, “ashlem” (to submit) and noun, “ishlama” (submission)…which, it might be noted, has the same Semitic roots as “shalom” (peace qua deference) in Classical Hebrew.

In some cases, hermeneutic chicanery is afoot. For example, “haqq” is often translated as “truth”; but it is actually from the Syriac term for “decree” (“h-q-q”). So the Abrahamic deity doesn’t establish Truth, he simply issues edicts–as with a ruler to his subjects (alt. as a master to his slaves). Thus “haqq” is about authority, not epistemology.

Sometimes CA terms are the result of scribal errors. Such flubs are very revealing about the lexical origins of Islam’s liturgical language. For example, the use of the peculiar moniker “zabur” for the Psalms is likely from the Syriac “zamuro” / “zamura”. In Syriac, the lower-case “m” can be easily mis-read as “b” if it is written in a straight manner. (Interesting work on this has been done by Gabriel Sawma in “The Aramaic Language Of The Qur’an”.)

Other terms came directly from the Nabataeans. For example, “djinn” (genie) was derived from the Palmyrene “ginnaye”. And the etymology of “masjid” [place of prostration; i.e. mosque] came from the Nabataean term, “masgida” / “masged[ha]”: venue for propitiation. This was related to the Syriac term for bowing down in prayer, “seghed[ha]”. Sure enough, that yielded the Arabic verb, “sajada” (a variation of which was “salah”).

But wait. What about when the KORAN ITSELF seems to refer to CA? What’s THAT all about? Well, actually, it never mentions a distinctly Arabic language; it only alludes to a language affiliated with the Arabs. It does this in three places. In 16:103 / 26:195, we encounter the phrase, “lis[h]an-un Arabiyyun mubin-un” / “lis[h]an-in Arabiyyin mubin-in” [tongue of the Arabs that is clear]. In other words: a tongue used by Arab peoples. WHICH tongue? Well, one that was CLEAR. The Koran then refers to THIS BOOK [“K-T-B”]…which, it stipulates, confirms and warns by using “lis[h]an-an Arabiyyan” [tongue of the Arabs] (46:12). (Note: “lis[h]ana” is the SYRIAC term for language.) Question: Would CA disquisition have been “CLEAR” to the average Bedouin listener in the 7th century? Nope. Not even close.

Regarding the plea that the Koran was ORIGINALLY composed in CA, a passage occurs in Surah 16 that is laughably on the nose. Verse 103 brings to mind the retort by Gertrude in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”: Thou doth protest too much. Why the need to make such a proclamation if the CA version of the “Recitations” was already a GIVEN?

Elsewhere, Islam’s holy book refers to itself as “qur’an[an]”, which it characterizes as “arabiyyan”. Thus: “recitations of the Arabs”–as in 12:2, 20:113, 39:28, 41:3, 42:7, and 43:3. In what language would that have been? Syriac. In 19:97 and 44:58, the book’s protagonist announces that he made the Recitations easy [“yassamahu”] for his target audience by rendering them “bi-lis[h]an-ika” [“in your tongue”]. And what was the “tongue of the Arabs” at the time? Syriac.

There is nothing in the Koran that indicates that there existed a cosmically-significant language that was unique to Arabia. And there is no reference to any alternative language–that is: such-and-such tongue AS OPPOSED TO “lisanun arabiyyun” (that is: a language that the Recitations were couched IN LIEU OF).

Interestingly, at no point does the book’s protagonist stipulate: “This is MY tongue.” So much, then, for the fetishization of CA…which seems to have become rampant only later on. The trope of CA being cosmically significant (that is: being god’s native tongue) seems to have gone into full swing by the 14th century…when, in the introduction to his “Lisan”, Ibn Manzur proclaimed that god had created CA superior to all other languages, revealing the Recitations in CA and thus making it the language of Paradise. (Gosh-golly!)

Here’s the problem. If god had composed the Recitations in an eternal language, he would not have ingratiated himself with a Bedouin audience by saying he delivered the final revelation in THEIR tongue [“bi-lis[h]an-ika”]. Instead, he would have notified them that they were blessed to be speaking HIS tongue. {72}

So what about when the Koran refers to OTHER languages? Regarding this matter, there are three verses that are quite telling. In 14:4, the book’s protagonist announces that he always sent his messengers with “lisani qawmihi” (the tongue of each messenger’s respective people). In 41:44, god proclaims that he would have never sent the Ishmaelites “qur’an[an] a’jamiyyun” (recitations of foreigners). Then–as if to illustrate how the terminology was being used–he distinguishes between “a’jamiyyun wa arabiyyun” (foreigners and arabs). And if this weren’t clear enough, 16:103 refers to “lisanu[n] a’jamiyyun” (tongues of foreigners). What might THOSE have been? Koine Greek. Classical Hebrew. Middle Persian. Ge’ez. (All medieval Arabs would have been privy to the existence of such languages.)

Effectively, the Koran only addresses why it was revealed in “YOUR” tongue (where the target audience was “arabiyyah”). This in no way attests to the existence of (what eventually came to become) CA. Interestingly, at one point, the Koran even refers to an Arab JUDGEMENT [“hukm arabiyyan”] (13:37). In other words: This qualifier was an ETHNIC designation, not an explicit linguistic demarcation.

At the time, Syriac did not refer to a particular people; it was known only as a language: “K-T-B-anaya” (which simply meant “that which is for writing”). {44} It is, of course, likely that different communities thought of Syriac in different ways. Hence Arabs’ use of “lis[h]an-an Arabiyyan”. {72}

Bear in mind that non-Syriac speakers sometimes referred to Syriac as “Arabiyyah” (language of the Arabs; spec. the Nabataeans), which did NOT correlate with what came to be CA (a.k.a. “Arabic”). (These were denizens of what the Romans called “Arabia Petraea”.) Similarly, Aramaic was referred to as “Aramaya” (language of the Arameans) and Syriac was referred to as “Suryaya” (language of the Syrians), “Atoraya” (Assyrian language), or even “Urhaya” (language of the Edessans), as Edessa (“Urhay” in Aramaic) was the home of Syriac. (Note: The 8th-century Mohammedan hagiographer, Ibn Ishaq, referred to Palestine as “Syria”. This seems to have been common practice. So “Suryaya” would have meant language of the Palestinian Arabs.)

Recall that, per Islamic scripture, the “Recitations” were originally composed in (what is referred to as) “the language of the Quraysh”: a peculiarly oblique description for a tongue that was supposed to be eternal—nay: the native language of the Creator Of The Universe. (Is this how god would have thought of his own tongue since the beginning of time?)

In the Koran, Christians are referred to as “Nasara”, which is from the Syriac moniker, “Nasraye”. There was no other language in which “Christians” were labeled in this way.

There is a caveat here. The existence of quasi-Syriac terms that ended up in the CA lexicon does not–in and of itself–reveal anything about when, exactly, CA emerged out of (Nabataean) Syriac; nor does the fact that such lexemes exist show for how long Arabs continued using Syriac after the Mohammedan movement had been inaugurated. Obviously, the fact that CA has Semitic roots makes it inevitable that it will have numerous cognates with Aramaic (i.e. the language from which ALL Semitic languages emerged) and its offshoots.

There are likely HUNDREDS of CA lexemes that share roots with Syro-Aramaic and/or with Classical / Mishnaic Hebrew (a different Semitic offshoot of Aramaic). Such cognates ALONE show nothing more than CA’s relation to its Semitic antecedents (and to its Semitic cousins). However, the fact that the terms listed here (distinctly Syriac lexemes that were important RELIGIOUS terms for the earliest Mohammedans) were still being used in the late 7th century…and on through the 9th century (that is: during Islam’s gestation period) reveals that Syriac was likely still an integral part of the lexicon. {10}

Other connections indicate that there was linguistic parity between the early Mohammedans and the Syriac peoples of the time. MoM’s foster sister, Huzafa / Shaima was the daughter of a man named “Al-Harith”. Who might that have been? Nobody knows for sure. But it’s worth noting that an Al-Harith ibn Jabalah was the leader of the Ghassanids until…amazingly…around the year MoM was (purportedly) born. The Ghassanids were Syriac-speaking, Christian Arabs who’s domain roughly coincided with Nabataea. (Al-Harith ibn Jabalah was later referred to as “Khalid ibn Jabalah” in Islamic lore: a rather suspicious alteration.)

Is this an odd coincidence? Perhaps. But it is also worth noting that three of MoM’s wives (Zaynab, Barrah / Maymunah, and Juwayriya) were the daughters of a man named [Khuzaymah ibn] Al-Harith. And Islamic lore also tells of three brothers who were pre-Islamic Hijazi (Syriac) poets (Marhab, Yasir, and Al-Harith), who were the sons of a prominent man named Al-Harith. It was their sister—also named Zaynab—who fatally poisoned MoM (to avenge her family’s death at the hands of the Mohammedans). Another Hijazi, an “Ubaydah” from Ta’if, is recorded as being one of the first twelve men to convert to Islam. HIS father’s name was Al-Harith.

The name’s use by the Ghassanids attests to the fact that it was used by those who spoke Syriac. This indicates that those who were involved in the gestation of Mohammedan lore were likely a Syriac-speaking people.

Also worth noting is the Arabic term for pilgrimage, “Hajj”. The term is likely derived from the Semitic term used for an auspicious occasion: “Hag[g]”. (The transition from the hard “g” to a soft “j” was routine—as with, say, “Hagar” to “Hajar”, “Gabriel” to “Jibrail”, and “Gehanna[m]” to “Jahannam”.) Testament to the fact that this was originally a Syriac term is the (original) label for one who participates in it: “Haggag” (later rendered “Hajjaj”) rather than employing the Arabic nomenclature “mu-” for “one who is [associated with]”, yielding the more familiar “mu-Hajjir”. As it turns out, the name of the most renowned Umayyad governor in the Hijaz was Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf of Ta’if. Al-Hajjaj (that is: “Haggag”) served under caliph Abd Al-Malik in the early 690’s. Recall that Ta’if had been the site of a cubic shrine to the goddess, Al-Lat; so the name would make sense for someone hailing from that location. Clearly, this Mohammedan governor had a SYRIAC name. Had it exemplified a CA onomastic, his name would have not used distinctly Syriac nomenclature.

Other clues abound. “Abd El[ah]i” or “Abd Elaha” (meaning “slave / servant of god”) was the Syriac moniker for Jesus of Nazareth. That was later rendered “Abd-ullah” in CA, as it first appeared in the inscription on the Dome of the Rock (constructed at the behest of Abd Al-Malik in the early 690’s).

More research can be done on key terms found in the archeological and textual record (including the earliest Islamic sources) during this period. Especially salient are lexemes that resemble Syriac precursors more than they do their eventual CA incarnations. Such research would involve identifying terms in the vernacular of the early Mohammedan movement that had not yet reached their final form (in Classical Arabic). We know that some of the lexemes in inscriptions from the last decade of the 7th century–and through the ENTIRETY of the 8th century–differ from (what came to be) distinctly Arabic lexemes. {2} This indicates that the language being used at the time was still (predominantly) SYRIAC. In other words: the new tongue was STILL DEVELOPING. {31}

Another indication that CA came much later than the Ishmaelite’s new creed is that Mohammedan lore lifted some of its terminology from PERSIAN sources. {13} Given the geo-political landscape of the time, this linguistic synthesis makes sense. Again, we need to consider the cultural / linguistic landscape of the time—environs in which certain memes germinated and proliferated. Through Late Antiquity, there was much interaction between the Syriac (spec. Nestorian) communities of the Middle East and the (Sassanian) Persians. Illustrative of this is the fact that the (Nestorian) Synod of Bet[h] Lapat c. 484 was convened at Gund-i-Shapur, which was located in Elam (even as the primary cities for the Syriac tradition were Antioch, Nisibis, and Edessa). There was even a Syriac patriarch at Ctesiphon from the late 3rd century (with Mar Papa bar [g]Aggai). This position continued through Babai the Great, who presided during MoM’s fabled ministry. Meanwhile, the (Arab) Lakhmids, who spoke Nabataean Syriac, had been in a long geo-political relationship with the (Persian) Sassanians. This naturally entailed a linguistic nexus. In locals like Kufa and Hir[t]a, it is likely that most people were bi-lingual. Hence the lexical vestiges of both Syriac and Middle Persian in the Koran are unsurprising.

As the Mohammedans conquered the region, the great Syriac patriarch, Isho’yahb II was active in Ctesiphon (628 to 645). These patriarchs continued to operate out of Ctesiphon until 780 (with [k]Hnan-Isho II), at which point the Abbasids had them move their seat to the new capital: Bagh-dad (in the vicinity of the by-then-defunct Ctesiphon). It makes sense, then, that the emerging vernacular was a synthesis of Syriac and Middle Persian.

Note, for example, the term for the flying horse that whisked the prophet into the heavens on the fabled “Night Journey”: “Buraq”. This was likely based on the Persian term for “lightning”: “barag”. Even the CA term for religion, “din” is a loanword from Persian. Meanwhile, the Arabic word for blue sky, “lazaward” (which served as the basis for the Latin “lazul[um]”) comes from the Persian “lajevard”. And during the Middle Ages, a moniker commonly used for Christians, “Tarsa”, was from the Pahlavi word “Tarsag”.

There are even some Koranic onomastics that were lifted from Persian. In 2:96, we hear about a pair of angels: Harut and Marut. Who were they? They are likely corruptions of the Middle Persian Kurdad and Murdad: demigods of Mount Masis (which was the Persian name for Ararat). Meanwhile, Jewish scribes likely adopted the tale of these two angels from the Babylonians. In any case, the author(s) of 2:96 were evidently hearing (orally-transmitted) tales in one language, then rendering them in their own.

Bear in mind: As with Syriac script, Pahlavi script was based on the (much older) Aramaic alphabet…even as its vocabulary was derived from the antecedent Persian language: Avestan.

Pahlavi religious texts included the “Bundahishn” [Original Creation], the “Denkard” [Compendium], the “Zartusht Namah” [Life of Zartust], and the “Arda Wiraz Namag” [Book of Arda Viraf]. One will find a slew of loan-words in the Koran from these texts–as with, say, “junah” (sin) and “barzakh” (barrier / partition). And “ishq” (passion) was from the Persian term “isht” / “ishka”.

In addition, we might note the term for storm, “tufan” (not to be confused with the monster from Greek mythology, the “typhon”, the etymological basis for “typhoon”…which may or may not be related). Even “dirham” (the medieval Arab currency) was derived from the Persian “drahm” (itself a rough cognate of the Greek “drakhme”). Prior to Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, only the Byzantine dinar / follis [rendered “fals” in CA] was used; though even those continued to be used across the Muslim world through the 10th century.

Interestingly, the moniker for the vaunted “House of Wisdom” in Baghdad during Islam’s “Golden Age” (“Bayt al-Hikma”) was–it turns out–simply the term the Arabs had always used for the royal PERSIAN libraries. (The Abbasids fashioned that storied institution as their own version of a palace library.)

Through much of the Middle Ages, Ishmaelites continued to use the Pahlavi term for the godhead: “Khuda” / “Khoda”. In Zoroastrianism, this was an alternate moniker for Ahura Mazda. It would be RETAINED in the advent of Islam, as documented by its usage in the “Frahang-i Pahlavig” c. 900, which illustrated how Persian (Pahlavi) and Semitic (Syriac) semiotics were being hybridized at the time.

This would make no sense had “Allah” been the original moniker–nay, proper name–used by the Mohammedans for the Abrahamic deity FROM THE GET-GO; as that would have precluded consideration of a Persian moniker later on. Tellingly, “Khuda” is STILL used by all Muslims living in regions east of Mesopotamia (that is: east of the Arab-speaking world), as in the expression “Khuda Hafiz”. And it remains in use in Turkish (vestiges from the Ottoman Empire) to the present day. Again, we see vestiges from the original Mohammedan vernacular…which, in the earliest period of the newfangled Faith, had not yet established a novel liturgical language.

Meanwhile, for the goddess, Venus, Ishmaelites opted for the Persian “Zahra” / “Zoreh” (alt. “[a]Nahid” when associated with “Anahita”) instead of EITHER the Syriac “Ataratheh” (a.k.a. “Atargatis”, likely derived from the early Semitic “Asherah”) OR the Old Arabian “Al-Uzza”, both of which had pagan connotations. (Such undertones likely hit too close to home for the burgeoning Mohammedan movement, which sought to eschew any lexemes with semiotic baggage.) This goddess was alternately rendered in Syriac as “Uzza[y]” by pre-Islamic Hijazis, for whom there was an Arabian shrine at Nakhla. It is THAT version of Venus that is referenced in commentary on the Syriac Bible by Theodore[t] bar Kon[a]i (in the 8th century). This probably explains the hang-up with the notorious “gharaniq” known as “Al-Uzza”.

(Meanwhile, the “gharaniq” “Man[aw]at” was the consort of the moon-god, Hubal; while “Allat” was consort of the Semitic god, “El”. For more on the three “cranes” mentioned in the “Satanic Verses”, see Appendix 5 of my essay, “Genesis Of A Holy Book”.)

And so we see that, even with respect to theonyms, CA was clearly not a fully developed language during Islam’s earliest period.

Looking at just the Koranic passages pertaining to heaven, we find a plethora of Middle Persian loanwords. Indeed, the accoutrements of Paradise, we are told, include “istabraq” (brocade), “sundus” (silk), “namariq” (cushions), “asawir” (bracelets), “rawdah” (luxurious garden), “zarabi” (golden carpets), “kanz” (treasures), and “rizq” (bounty / provision). We even encounter details like the contents of the chalices (“mizaj”) provided in heaven: musk (“misk”), camphor (“kafur”), and ginger (“zanjabil”)…ALL of them variations on extant Persian lexemes. Meanwhile, the Arabic “zafaran” comes from the Pahlavi “zarparan” (saffron). {26} (The coveted spices, “murr”–often rendered “myrrh”–came straight from the Aramaic.)

There are also “houri”: the coterie of angelic beings in heaven. That was a take-off on the Zoroastrian “pari” (fetching heavenly maidens populating Paradise). The appellation for the celestial luxury resort ITSELF (“fir’daws”), from the Avestan “fairi-daeza”. (Writers of both Syriac and Koine Greek texts also adopted the Persian lexeme for “Paradise”.)

All this makes perfect sense, as the Mohammedan view of heaven was largely lifted from Zoroastrian theology–replete with its seven levels and buxom concubines. In other words: It is no coincidence that terms pertaining to heaven come from the Persian rather than Syriac vocabulary. As usual, the etymology of the relevant vernacular tracks with the origins of the (appropriated) lore. {24} To reiterate: The Lakhmids afforded the primary means by which other Arabians adopted Persian terms–especially ones that ended up being couched in an Abrahamic idiom. Even the CA term for “veneration” (“khudu”) is from the Persian term for “that which is venerated” (i.e. a deity): “khoda” / “khuda”.

There are myriad other clues to the Persian basis for certain elements of CA. It’s worth conjecturing that “abi” is an alternate version of “abu” because the Persian preposition, “of” (“-i”) was at one point used to modify the Semitic word for father (“ab”). The same thing may have occurred with “bani” vs. “banu” for “tribe of”.

Due to the fact that Muslims today are inclined to elide the origins of their liturgical language, it is rarely acknowledged that the etymology of the Abbasid capital, “Baghdad” was based on the Persian term for “god’s gift” (“boghu-dat”). This prompts the obvious question: Why in heaven’s name would the caliph at the time (Al-Mansur c. 762) have named his new capital city using PAHLAVI (which, it might be noted, was itself based on Babylonian Aramaic; and was the language of his NEMESIS)? If CA was already considered god’s language, such onomastics would not have made any sense.

The explanation is clear: The Mohammedans did not yet have their own (fully-developed) language…lest the city’s name would have instead been: “hiba” of “Allah”…instead of “boghu-dat”. {26}

It should come as little surprise, then, that early on, we encounter apocryphal tales about “Salmon the Persian”, who is purported to have rendered the “Recitations” in Middle Persian (i.e. Pahlavi) during Mohammed’s ministry. This attests to the fact that the “Recitations” did not need to be in CA, nor were the verses considered to have been in any one particular language at the time. To wit: There was no requirement that the Last Revelation be rendered in some (ostensibly) eternal tongue.

Another notable clue is Koranic morphology. As it turns out, the verbiage exhibits the kind of formulaic elocution that is endemic to orality (a signature feature of pneumonic devices used by those who would memorize verse in pre-literate societies). That is to say, the “Recitations” are indicative of material devised as an oral tradition rather than something that was (originally) written. It is apparent that the verse was contrived ad hoc, using stock phraseology (and other pneumonic gimmicks) to ensure catchiness / stickiness (for maximal contagiousness and memorability). A notably high incidence of formulaic elocution occurs in Surahs 61 and 63. (For more on this point, see Andrew G. Bannister’s “An Oral-Formulaic Study of the Qur’an”.)

Clearly, CA was almost entirely derivative–primarily an admixture of (Nabataean) Syriac with some Old South Arabian and a dollop of Middle Persian…which is exactly what we might expect for a language that emerged at the time and place that it did. We might note that CA was not the only language that was influenced by Old South Arabian. The ancient Ethiopic language, Ge’ez also incorporated elements. (Recall the enumeration of Old South Arabian inscriptions earlier in this essay.) Of course, ALL of that was ultimately Sinaitic (read: Canaanite).

Make no mistake: The lexemes outlined here are not accidental cognates; they are exactly what we’d expect to find in the evolution of a morpheme along linguistic lineages…within a memetic ecosystem where ORAL transmission predominated. Such etymologies are unsurprising–especially in light of genealogies that shared a common Abrahamic heritage. Such rampant cooptation is, indeed, what occurred throughout the Middle East during the Dark Ages.

As is well-known, proto-CA (from Kufic texts to the inscription on the Dome of the Rock) did not have diacritical marks, leaving vowels “up in the air”, as it were. This is an omission indicative of Levantine Semitic languages, not of the Hijaz (nor of southern Arabia); as the latter script was already equipped with vowels. In other words, vowel-neutrality was a feature of (Nabataean) SYRIAC, not of Sabaic et. al. This fact makes plain the origins of Koranic verse. Had the Koran originally been composed in an Old Arabian language, it would not have required the later glyphic emendations found in the Garshuni script. It was clearly a LATER off-shoot of Syriac, with morphologic and orthographic features that clearly illustrate subsequent modifications.

One needn’t have a PhD in either paleography or philology to notice any of this.

In assaying the MORPHOLOGICAL aspects of relevant etymologies, we might also refer to the flawed onomastics involved with the establishment of proper names in CA. Take, for example, the etymology of the name of the arch-angel that visited MoM. The original Semitic term would have been “G-B-R[a]-El”, meaning “god my strength”. {32} In CA, this WOULD HAVE been rendered with the root “A-Z-R[i]” [my strength]. However early Mohammedans probably would have balked at a direct transliteration into CA given that “Azra-El” (which meant “help god” in an earlier Semitic lexical context) would have been associated with the angel-of-death, who went by that name. Consequently, the name Mohammedans ended up adopting for the angel was based exclusively on phonology. That is: They simply repeated what they HEARD (likely a phonetically tweaked version of “Gabriel”), thereby yielding “Jibr[a]il” (pronounced “Jibreel”). This etymological discrepancy must have arisen AFTER Aramaic bifurcated from Hebrew–that is: from a late offshoot of SYRIAC. {34}

So what does “Jibr[a]il” mean? Nothing. It’s just an onomastic adaptation based entirely on phonetics (as would be expected from orality) rather than on semiotics (which would have been honored had there been an understanding of the name’s Hebrew etymology). It is more morphology than etymology that propagates when the primary means of transmission is orality. Hence “Jibr-eel” rather than “Gabri-El” for the arch-angel in Islamic scripture.

Indications of the Syriac origins of CA can be found in the names of auspicious figures as well. In the Koran, JoN is referred to as “Issa”, which is a derivative of the Syriac “Isho” (which was itself based on the Aramaic name, “Yeshua”). Noah is referred to as “Nuh”, which is a derivative of the Syriac “Nu[k]h”. The “crane” [goddess] known as “Uzza” derives from the Syriac “Uzzay” rather than from the Greek moniker, “Ourania”. (She was worshipped primarily by the Banu Shaiban at Nakhla.)

Sometimes the CA moniker is the SAME as the antecedent Syriac–as with the CA name for “Eve” (“Hawwa”), which was simply a reiteration of the Syriac, a variant of which was the Hebrew “[c]Hawwah”. As it turns out, for Arab pagans, “Hawwa” was the (Syriac) name of the legendary ancestor of humanity, for whom there was a shrine at Jeddah. (This etymology makes sense, as “Hawwa” may have been a play on the Semitic word for life, “hayya”.) The CA term for John (“Yahya”) is from the Syriac “Yohanna[n]” via Kufic.

In a minor foible, “Yunus” (Jonah) is referred to as “Dhul-nun” [One of the fish] in 21:87; which is from the Syriac lexeme for “fish” (“nun”). In other words, the Creator of the Universe (putative author of the “Recitations”) seems not to have been aware of the prophet’s given name. That is: His knowledge was oddly limited to what happened to be available in Syriac source-material. All the authors of the Koran seemed to know is that he was the guy in the story about the big fish. {28}

According to Exodus (2:10), Moses was adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter; yet according to the Koran (28:7-9), he was adopted by Pharaoh’s wife. In Islamic lore, Pharaoh’s wife is referred to as “Asiya” (who is then executed by her husband for converting to Islam). As it turns out, “Asiya” was the Syriac term for “healer” / “provider of solace”; and was commonly used in Syriac lore up through the Chaldean rite (ref. Paul Bedjan’s “Acta Martyrum Et Sanctorum”). The term was also used in Middle Persian. “Asiya” eventually came to be used as a term for a pious woman.

(Note that there is evidence of onomastic confusion on the part of later Islamic expositors; as “Asiyah” is referred to as the daughter of “Muzahim” by Al-Kisa’i; per Ibn Kathir. As is often the case, nobody could agree on the details of ancient folklore, including the parentage of an exalted figure like the Pharaoh’s pious wife.)

The name was clumsily rendered in Greek as “Asenath” (“servant of Neith”), as with the daughter of the royal priest, Potiphera of On (a.k.a. “Potiphar of Heliopolis”); who became the wife of Jacob’s heroic son, Joseph.

What makes all this even more interesting is that, elsewhere in the Koran (33:4), god forbids adoption…even as it emphasizes the fact that Moses was Pharaoh’s adopted son. The Koran also speaks of Joseph ben Jacob being adopted by Potiphera (referred to as “Al-Aziz” in 12:21). We are expected to believe, then, that god changed his mind on this issue; and did so exactly when it suited MoM’s (sexual) interests.

There are various other terms that serve as tell-tale signs of CA’s origins. We might also note that the Nabataean (Syriac) term “ka’abu” referred to the cubic shrine (comprised of stone blocks) at Petra. The shrine was used by the Nabataeans to pay tribute to their god, Dushara, at a shrine that was known as–you guessed it–the “Ka’abu”. Hence the term Mohammedans ended up using for the Meccan cube: “kaaba”. (For more on this, see my essay on “Mecca And Its Cube”.)

Thus: Simply by comparing certain words in the CA lexicon to Syro-Aramaic correlates, one can establish the etymology of key Koranic terms.

Predictably, many of the lexical limitations of Syriac translated to the discursive shortcomings found in Koranic verse. For instance, there was no word for “zygote” / “embryo” in Syriac, so the authors were forced to go with “blood-clot” when they opted for using CA (in their daft attempt to unsuccessfully explain embryology; ref. 96:2). As it turns out, the “blood-clot” meme for embryos proliferated in the region during Late Antiquity. Would god’s propitious disquisition have been so hamstrung by the crude vernacular of the Dark Ages? {33} And would he have also succumbed to the puerile superstitions that were popular amongst senescent Bedouins at that particular time? (Memo: A zygote is not a blood-clot.)

After scrutinizing the etymologies found in the Koranic lexicon, it becomes hard to ignore the fact that the “Recitations” exhibit distinctly Syro-Aramaic features. Indeed, the text often employs phraseology that is unique to Syriac; just as it is used to tell apocryphal tales that were unique to Syriac sources. {17}

It is telling that documents from the 7th century were first translated into Garshuni (proto-Arabic using a Syriac script), then to Armenian, then to CA. This would not have occurred in that sequence had CA already existed.

Given all this, it makes sense that the earliest scripts used for CA were Garshuni (i.e. the earliest iteration of CA using the Syriac alphabet), an offshoot of the Nabataean-influenced “khatt al-Kufi” (a.k.a. “Kufic”, which was named after the place where it was first found: the city of Kufa in central Mesopotamia). {2} To reiterate: Kufic was a proto-CA script which exhibited the orthography of the Nabataean alphabet; thus illustrating the new liturgical language’s Syriac roots. {3} As mentioned earlier, other intermediary scripts were Estrangela, Serta / Serto, and Madnhaya / Swadaya.

And as we have seen: The “Sana’a” Koran–the earliest surviving version of Islam’s holy book–was composed in the Kufic script. The codex was likely produced after Abd al-Malik’s reign, and ended up in the south-Arabian town of “Ma’rib”. In other words: pre-CA script was still used for compilations of the “Recitations” as far down as Yemen (per the Sana’a manuscript). That is: The script was being used from Kufa (present-day Najaf) down to Ma’rib (Sana’a); which entails the entirety of the Hijaz!

Unsurprisingly, Islamic authorities have been obdurate in limiting scholars’ access to these manuscripts; thereby severely constraining OBJECTIVE evaluation of the text in each case. Clearly, there is much about such early manuscripts that they would much prefer remain verboten.

Another clue can be found in Islamic accounts of the “city of the prophet”. In the writings of Al-Waqidi, there is reference to a Nabataean “souq” [market] in Yathrib during the pre-Islamic period, wherein he uses the label, “Nabati” for the patrons. This is very telling. Nabataeans evidently had a significant presence in the city that would become Medina. Odd that it is never mentioned that MoM had to contend with any foreign tongues when he arrived and became the city’s cynosure. This only makes sense if everyone in Yathrib already spoke the same language.

There are other hints here and there. For example, in 11:79, the word used for the pronoun “you” is “ha’ula’i” (a variant of “hawila”), which is from the Syriac “hala’in”.

The dialect of Arabic that–to this day–retains palpable traces of its Syriac antecedent is Lebanese Arabic. Notably: the vowel, “e” in Lebanese Arabic comes from the Syriac “rboso”—a feature that is not found in the medieval Arabic that became the basis for “fus[h]a”. This phonetic vestige is preserved in the Lebanese pronunciation of their own country: “Lebnen” rather than the medieval Arabic “Lubnan”.

In sum: Koranic vernacular offers plenty of clues as to its linguistic (esp. lexical) origins. {17} CA was, to be blunt, ANYTHING BUT a timeless language. As I hope is plain to see here, CA was an accident of history like ANY OTHER language that has ever existed.

If CA were, indeed, an eternal language (that is: the “native” language of the Creator of the Universe), then the Abrahamic deity would have been providing all his revelations to the Abrahamic prophets…starting with Adam, through Abraham, to Moses and thereafter…IN CLASSICAL ARABIC.

If that were the case, we are left to explain how CA’s Semitic precursors inexplicably emerged (starting with Ugaritic, Ammonite, Eblaite, Phoenician, and Old Aramaic); as they would have been a divergence from an extent tongue: CA. Even more complicated, this millennia-long divergence from THE primordial language would have needed to continue on through Samaritan, Babylonian Aramaic, Mandaic, Syriac, Palmyrene / Nabataean…not to mention additional tangents like Mishnaic Hebrew and Chaldean / Madenhaya (as well as the variants in southern Arabia: Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramitic, Himyaritic, Sayhadic, and Minaic / Madhabic)…that is, before eventually coming BACK AROUND to the nominal language…which had existed since the beginning of time. (!)

Such a far-fetched “just so” story strains credulity to the breaking point.

The fact that proto-Sinaitic tongues also morphed into Ethiopic variants (like Ge’ez) as well as Kurdish variants (like Turoyo / Suroyo / Surayt, written in the Serto script) is further evidence that such a round-trip linguistic journey would have been inconceivable.

Another clue worth considering: Vestiges of Old Arabian persist to the present day–as with Faifi and Razihi (likely due to the fact that the Yemeni region was not quite as saturated with Syriac as was northern Arabia). Had CA been the tongue used by Hijazis all along (that is, during MoM’s lifetime), Arabians would not have diverged from it after Islam’s liturgical language had been established (viz. delivery of the Last Revelation).

As I hope to have shown, when it comes to evidence for–or, at least, indications of–the Syriac roots of CA, there is an embarrassment of riches. This goes beyond just that which is found in the Koran itself; the general liturgical language is festooned with vestiges of its Syriac beginnings.

The examples go on and on. The CA term for the Christian Gospels (“Injeel”) is an Arabization of the Syriac moniker found in the Peshitta, “awongaleeyoon” …which was itself derived from the Koine Greek “eu angelion” [alt. “evangel”], which was derived from “ef-aghelia”, meaning “good message”.

It might be noted that, in exalting the “Injeel”, the authors of the Koran likely had in mind Syriac apocrypha rather than the canonical Gospels (i.e. material selected at the Council of Nicaea), which were primarily rendered in Koine Greek…pace the Syriac “Diatessaron” (later rendered the “Peshitta”), which would have been circulating in the Middle East at the time.

How so Greek? The Byzantine Empire was the neighbor to the northwest. The term used for the Gospels was not unique. The alternate name for Satan, “Iblis” is a variation on the Greek “diabolos”. Ten other examples of Arabic lexemes that came from Hellenic terms:

- “harita” (map) derived from “hartis”

- “kamous” (ocean) derived from “oukianous”

- “iklim” (region) derived from “kilma”

- “satara” / “ustura” (written history; legend) derived from “historia”

- “falsafa” (philosophy) derived from “philo-sophia”

- “al-kimiya” (alchemy; chemistry) derived from “khemeia”

- “iyaraj” (sacred) derived from “[h]iera”

- “namus” (law) derived from “nomos”

- “barbari” (barbarian) derived from “varvaros”

- “burj” (castle) derived from “purgos”

Even the Arabic term used for “Greek” ITSELF, “Yunani” derived from the endonym, “Ionas”. Clearly, CA was not a timeless language. That the Ishmaelites borrowed from the Byzantine lexicon FURTHER attests to the derivative nature of (what would eventually become) their liturgical language.

Are we to suppose that the Creator of the Universe clandestinely planted these terms in the Byzantine lexicon…in the hopes that they would eventually be coopted into the lexicon used by those to whom he would (later) deliver the Final Revelation?

As with any newfangled language, the earliest speakers of CA were appropriating terms from whatever languages happened to be impinging upon them. The result is a smattering of loanwords–primarily from its precursor, Syriac; but also from Persian (from the Sassanians) and Greek (from the Byzantines). CA is god’s native tongue? Don’t be ridiculous.

In the end, Syriac was the over-riding basis for CA, as THAT is what the Ishmaelites spoke; and it is from SYRIAC sources that they cribbed their lore. The CA term for messiah (“masih[i]”) is from the Syriac “mshyh”, which was itself derived from the Aramaic “meshiha” (another variant of which is the Classical Hebrew “mashia[c]h”). Thus “Masihi” was the Syriac term for followers of the Messiah. Recall how commonplace this moniker was–as during MoM’s lifetime, there were several other claimants propounding revelations–that is: claiming to be the latest Abrahamic prophet, sent to the Arabians by “allah” (most notably, Maslamah ibn Habib; a.k.a. “Musaylimah”).

MoM was merely the claimant who prevailed. This is yet another reminder that history is written by the victors. (Note that the modern Arabic term for Nazarene is “Nasiri”; while the term for Christian remains “Masihi”.)

We might also note the primary terms used for “Christian” in Dar al-Islam throughout the Middle Ages: “Nasrani”. THAT was the Syriac term for “Nazarene”. We’ve already discussed the CA term for a non-Mohammedan: “kafr”. It might be noted that this term of alterity was a variation on the Syriac verb for “deny”: “kapar”. As mentioned earlier, it took on the meaning “conceal” (that is: obfuscate) in its CA incarnation. Hence it is typically interpreted as “one who conceals [the truth]” (i.e. “denier”; one who obfuscates what is true). To suppose that this has nothing to do with Syriac antecedents is far-fetched.

The most obvious evidence for the Syriac origins of CA lay in the moniker used for the Ishmaelite godhead–a revamped conception of the Abrahamic deity. {18} As mentioned earlier, “allah” was derived from the Syriac, “eloah” (alternately rendered “alaha”)…which was based on earlier Semitic incarnations (i.e. the Aramaic “elah[a]”). {19}

Lo and behold, references to “allah” were used in material by the Arabian poet, Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulma…who wrote his poems a generation before MoM’s ministry. (!) This stands to reason, as Jews and Christians in the region during Late Antiquity ALSO typically used “eloah” / “elah[a]” (as opposed to the Classical Hebrew: “El” / “Elohim”) when referring to the Abrahamic deity. It’s no wonder this ended up becoming the primary appellation for the Koran’s protagonist.

Again, some key terms can be directly traced all the way back to their Aramaic roots. For example, “sajda” / “sujud” comes from the early Semitic root “S-G-D” (meaning prostration)…via Syriac intermediaries. Thus the term “masjid” for the place of prostration. The term for “slay” (“yuqatil” / “uqtul[u]” / “[y]aqtul[u]”), which is used throughout the Koran, is from the early Semitic root “Q-T-L”…via Syriac intermediaries. Etc.

It should be obvious from the present survey that the origins of Islam’s liturgical terms lay in the Levant, not in Arabia. (Old South Arabian was clearly not the primary source of the CA lexicon.) The supposition that CA is an eternal language is belied by its obviously derivative nature. What is telling is not merely THAT it is derivative; but FROM WHENCE it is derived, and WHEN that derivation occurred. But the evidence all points to a certain course of events. Even as recently as the 12th century, the Arab philologist, Abu Mansur Mauhub al-Jawaliqi of Baghdad was candid about “foreign terms found in the speech of the ancient Arabs and used in the Koran” (ref. his explanatory “Kitab al-Mu’Arab” [Book Of Words Used In Arabic]).

To conclude: The traces of the Koran’s Syriac origins can be found not only in its thematic content, but in its vernacular. It is a vernacular that–it turns out–was anything but timeless. This was no secret at the time.

The derivative nature of CA belies the claim that it is god’s native tongue…lest we suppose that the Creator of the Universe sporadically planted lexemes in alternate vernaculars (not only Syriac, but also Middle Persian) so that they might later be adopted by the Ishmaelites. To then claim that CA existed since the beginning of time is bonkers.