The Syriac Origins of Koranic Text

October 26, 2019 Category: Religion

A FURTHER EXPLORATION OF RELEVANT HISTORICAL EXIGENCIES:

When it comes to assaying the origins of Mohammedan lore, it is worth recapitulating some of the most notable Syriac sources adumbrated in my previous essay: “Syriac Source-Material For Islam’s Holy Book”. Here are thirty major works–all of which were available in Syriac during the relevant period. As I showed in the previous essay, ALL of these works had palpable influence on Mohammeden lore…and thus on Islamic scripture:

- The Conflict Of Adam And Eve With Satan {59}

- The Genesis Rabba by Rabbi Hoshayah

- The Mekilta by Rabbi Ishmael ben Elisha

- The Testament Of Solomon

- The Covenant Of Damascus

- The Jewish Apocalypse of Ezra (a.k.a. the second “Book Of Esdras”; alt. 4 Ezra)

- The (first) Book Of Enoch

- The Book Of Jasher (as well as the “Pirke” of Rabbi Eliezer)

- The Book Of Jubilees

- The Book Of Tobit

- The Targum Of Esther (as well as various other Syriac Targum-im)

- The Epistle Of Barnabas

- The Gospel Of Peter

- The [Infancy] Gospel Of James

- The Infancy Gospel Of Thomas (and its derivative: the Gospel Of The Infancy Of The Savior)

- The Book Of The Nativity Of The Blessed Miriam, And The Savior’s Infancy (a.k.a. “pseudo-Matthew”)

- The Psalms of Thom[as]

- The Acts of Peter and Andrew

- The Apocalypse of Baruch (alt. 2 Baruch); The Last Words Of Baruch

- The Apocalypse of pseudo-Methodius {40}

- The Apocalypse of Abraham

- The Passion Of Sergius And Bacchus

- The Romance Of Alexander by Callisthenes of Olynthus (and its Syriac offshoot: “The Legend Of Alexander”)

- The Demonstrations by Aphrahat of Ashuristan (inspired by the Book of Daniel, which was itself originally composed in Aramaic)

- The Cave Of Treasures by Ephrem of Nisibis

- The Seven Sleepers Of Ephesus by Jacob of Sarug

- The Enchiridion by Jacob of Edessa

- The Book Of Treasures by Jacob of Edessa

- The Book Of Perfection by Sahdona of Halmon

- The Book Of the Scholion by Theodore bar Konai

Other major Syriac tracts included the Nedarim, Nazir, Me’ilah, Keritot, and Tamid. (To see the vast reach of Syriac Christianity, we might note the Nestorian Stele at Chang’an (now Xi’an) from c. 781.)

The most significant sources from which Mohammedan lore was cribbed were the Syriac versions of canonical scripture–that is: the holy books of the Syriac church. Hence the prevalence of the Diatessaron (along with its counterpart, the Evangelion Dampharshe); which was followed by the Peshitta (along with ancillary material like the illuminated “Rabbula” Gospels). The Diatessaron, commissioned by Tatian in the 160’s (copies of which include the Khabouris codex, the Sinaiticus codex, and the “Curetonian Gospels” from the 4th century) was rendered as the “Peshitta” [simple text] c. 508. (See footnote 34 of my essay on “Syriac Source-Material For Islamic Lore”.)

All THAT was in conjunction with other significant texts like the Nestorian Psalter (the Syriac “Book of Psalms”) mentioned earlier. EVERY ONE of these Syriac sources influenced Mohammedan lore (spec. with regard to the composition of the Koran and Hadith). {20}

As verse 5 of Surah 25 concedes: Much of MoM’s audience was already familiar with the material he was hawking. This long list explains how this was so.

There were, of course, other works of Abrahamic lore that likely circulated in Syriac–throughout the region–at the time. Notable were the Odes of Solomon and Psalms of Solomon, codices of which are housed at the John Rylands Library (also ref. the Nitriensis codex from Scetis, Egypt). The “Didascalia Apostolorum” from Antioch c. 230 had been based on the antecedent (Greek) “Didache” from the 2nd century. Other Syriac works circulating at the time included the “Apocryphon of John” (used by the “Audians” of Mesopotamia) and the (lost) Gospel of Bartholomew (a.k.a. the “Resurrection of Jesus Christ” by Bartholomew; and/or “The Questions of Bartholomew”).

Also of note is the (Syriac) “Apocalypse Of James”, which was likely composed in the early 8th century. This book excerpted material from Severus “the Great” of Gaza / Pisidia (who served as the patriarch of Antioch) and Jacob of Edessa (who served as the bishop of Edessa). It also included selected passages from the (Syriac) Doctrine of Addai. It seems to have been intimately related to the (Syriac) “Apocalypse Of John The Little”—a tract that actually addressed the (newly) emerging Mohammedan Faith. (!) Funny how this reaction—in the 8th century—comes a century LATE (with regard to the standard Islamic narrative; wherein the timeline begins with the “hijra” c. 622; and the major Ishmaelite conquests a decade later). According to the “Apocalypse Of John The Little”, the touchstone event for the Mohammedan movement was the reign of caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (c. 685 – 705). This comports with the timeline proposed in my other essays on the matter: “The Meccan Cube” and “Genesis Of A Holy Book”.

With regard to eschatology, the “Apocalypse Of John The Little” takes its inspiration from the Book of Daniel. In keeping with this, the tract seems to be in dialogue with other Syriac Apocalypses of the time—specifically those of pseudo-Methodius (as well as the tract from which the quizzical “Edessene fragment” comes). This is a reminder of how important it is to understand the Syriac milieu in which the Mohammedan creed germinated. NOBODY—including the Ishmaelites—was (yet) speaking the language that came to be dubbed “Arabic”. Everything was articulated in Syriac during the relevant period.

It would be one thing if the standard Islamic narrative de-emphasized these key factors; but it leaves them out entirely. This omission is peculiar. It’s as if those who crafted the (invariably self-serving) historiographies had something to hide. Put another way: If those propounding conventional wisdom had nothing to hide, there would have been no reason to so completely elide the integral role that Syriac played in the environs of early Islam. Such obfuscation is a red flag that the elucidation of Truth was not the sine qua non of those who composed the Hadith collections.

There are various cases in which the cover-up ends up being more incriminating than that which was being elided. Take, for instance, the so-called “Apocalypse of Samuel”—a tract that was falsely attributed to the 7th-century Coptic monk, Samuel of Kalamoun (a.k.a. Saint Samuel the Confessor). It was actually composed during the Fatimid period (10th thru 12th century). The tract addresses the shifting of Egypt’s lingua franca from Coptic to medieval Arabic—a process that was documented by Abu’l Qasim ibn Hawqal of Nisibis in the late 10th century. (Tellingly, the Apocalypse of Samuel came to exist in only Arabic translations.) {60}

In the region, it was common for practitioners of Abrahamic lore to misconstrue Syriac sources as original sources. Thus heterodox apocrypha crept into the lore. Possible Syriac influences in the region went on and on–as with the Acts Of Thomas / Judas [“Didymus”] from the early 3rd century as well as the Acts of Andrew and Bartholomew from the 5th-century (to mention yet TWO MORE).

Most of these apocryphal texts were rendered in Aramaic and/or Syriac–as attested by the Dead Sea Scrolls, excavated from the caves at Qumran.

All this is in addition to the panoply of Syriac liturgical material that was available to the earliest Mohammedans–notably: the writings of Narsai of Ma’alta (who worked at the schools of Edessa and Nisibis). And recall the profusion of Talmudic material (i.e. the Aggadah and Gemara) circulating IN SYRIAC throughout the Middle East at the time–as with the Mekilta and the Genesis Rabbah. {21} One cannot even pretend to understand the memetic environment in which Mohammedan lore germinated without being familiar with these Syriac works.

To reiterate: It was not as if people throughout the Middle East were sitting around reading all these books. Rather, these books were the source of folklore that circulated orally, and propagated in a rather haphazard fashion (as is the case with oral transmission over the generations) throughout the region. {23}

We have looked at lexical parity; but we needn’t limit ourselves to etymology. People also left a trail of CA’s genesis in terms of orthography. Early Hijazi (a.k.a. “Thamudic”) scripts had several variants–all of which were descendants of proto-Sinaitic. First, from the NORTH, was Safaitic (i.e. Levantine), which was based on the Nabataean incarnation of Syriac. THAT was the primary basis for proto-CA. Second, from the SOUTH, was the Sayhadic family of scripts, which were used for Old South Arabian (itself a Sinaitic language). To review, these included:

- Qatabanic (alt. Qatabanian)

- Sabaic (alt. Sabaean; as with the so-called “musnad”)

- Hadramautic / Himyaritic (i.e. Yemeni)

- Hasaitic (i.e. eastern Arabian)

- Minaic / Madhabic (alt. Minaean)

Sayhadic (spec. Sabaitic and Minaic) scripts were used by the Kindah kingdom (esp. at their capital, Karyat al-Faw), which means that the spoken languages (Sabaean and Minaean) were Old South Arabian.

As mentioned earlier, inscriptions in Arabia (typically categorized as “ancient north Arabian”) could found in the Hisma desert, at the Tayma oasis, at Dadan [alt. “Dedan”; now known as “Al-Ula”], and at Dumah. {2}

It is important here not to confuse Old (north / south) ARABIAN for some earlier version of ARABIC. This taxonomic glitch is exacerbated by ill-defined terms like “Old Arabic”–which only elides the ACTUAL origins of CA. (Classical Arabic IS the oldest Arabic.) Another misleading term is “Nabataean Arabic”–which would be like saying “Romanized Castilian”. (It would be inane to contend that Latin was just an early form of Spanish.)

While (Nabataean) Syriac was the primary basis for proto-CA, it might be noted that CA (in its fully-developed form) likely emerged after Syriac was infused with a few elements the above (indigenous) Arabian languages / scripts, as one would expect. This admixture would have occurred during the time the Arabs (the “Saracens”) adopted a distinctly Ishmaelite identity (starting at the end of the 7th century, and on through the 8th and 9th centuries)…and subsequently asserted their dominion. This would have been an ad hoc process.

It is THAT process that would initially lead to Kufic…and, eventually, to what finally came to be (what we now know as) “Classical Arabic”. Thus CA can best be thought of as a linguistic alloy of (Nabataean) Syriac and sparse vestiges of some of the Old Arabian languages. {43}

To reiterate: The script that was EVENTUALLY used for proto-CA was Nabataean–a variation of Syriac based on Aramaic. Thus CA script was a descendent of the Nabataean alphabet via the Kufic script–used during the embryonic stage of CA’s development (which, as we’ve seen, seems to have been inaugurated at Kufa in the early 8th century). {3}

Tellingly, some of these proto-CA inscriptions made use of Syrio-Aramaic lexemes rather than lexemes eventually used by CA–as with “bar” instead of “ibn”. This is attested by the Harran inscriptions at (Lihyanite) Dedan (a.k.a. “Hegra”) in northwestern Arabia…which, it so happened, was a place later ruled by the Nabataeans. This is very telling.

To be clear: Initially, Arabian inscriptions (esp. the Old North Arabian inscriptions listed above) simply used Aramaic-based vernacular…even as they were written in either Nabataean script (as with the Namarah inscription near Damascus and the various inscriptions at Sakakah) or epigraphic “Old South Arabian” script (as with the inscription at Qaryat al-Faw in the Nejd). {2}

In a few cases, the inscriptions would make use of some local vernacular that would later emerge in the development of CA (ref. the inscriptions at Ein Avdat in the Negev and at Umm al-Jimal in Syria). It would be a mistake, though, to interpret the incidence of cognates as evidence that CA already existed at those earlier times. That’s not how the evolution of language works. EVERY language has precursors. The existence of lexical / phonological antecedents with recognizable elements of the later language does not mean the later language existed AS SUCH at that earlier stage. To construe such similarities as evidence of the later language ALREADY existing (as a distinct language) is to reverse causation. It would be like a son noting that his father HAS HIS eyes. Not only is such inverted causality like saying the parent has the child’s eyes BECAUSE OF the child; it’s like taking the resemblance as evidence that the child ALREADY EXISTED (in an earlier form) at the time of the parent’s birth. (!)

An analogous mischaracterization would be, say, looking at the runes of northern Europe from the Dark Ages and taking that as evidence that “English” somehow existed (in an earlier form) well over a thousand years ago. In reality, English as we now know it was primarily based on an admixture of Norman and Old Saxon…which were both off-shoots of Frankish…which was itself an admixture of Vulgar Latin and Germanic tongues dating back to Late Antiquity. The use of Frankish during the Dark Ages is not evidence that English was already in use at the time. Though they served as a basis for English, it is not accurate to see Norman and Old Saxon (or even the Celtic “Old English”) as EARLY FORMS OF English.

CA emerged from Nabataean Syriac. Historical events explain why all this came to pass as it did. The Lihyanites, who preceded the Nabataeans, also established the city of Dedan (later called “Hegra” by the Nabataeans; referred to as “Al-Hijr” in the Koran; now known as “Mada’in Saleh”), at which was erected the massive “Qasr al-Farid” [“lonely castle”] in the early 1st century. {25}

Of course, Saudi archeology is like a Taliban bikini contest. It doesn’t exist; and it is prevented from existing for explicitly religious reasons. This should be obvious to even a casual observer. There are many things that Wahhabis (and Salafis) would very much prefer nobody ever found out about Islam’s ACTUAL history; as such disclosure would undermine the foundations of their ramshackle dogmatic edifice. The fragility of ANY house of cards demands that they be protected from even the mildest perturbation.

Consequently, we encounter an alluvion of legerdemain whenever it comes to this subject-matter. Disingenuous historiographers sometimes assign the descriptor “[early] Arabic” to Kufic inscriptions–and, even more absurdly, to earlier Nabataean inscriptions–so as to retro-actively ascribe CA to an era that predates its genesis. {2} This is done so that they can pretend CA existed during MoM’s lifetime. Such brazen dissimulation is risible, yet unsurprising. Short of engaging in such taxonomic gimmickry, they would be forced to concede that the “Recitations” were originally composed in a language other than Islam’s liturgical language, thereby subverting the narrative on which their ideology depends.

Hence the charade persists in many circles to the present day. Even now, expositors in the Muslim world insist that the fabled writer, “[Abu Musa] Jabir ibn Hayyan” of the Azd (variously said to have been from Tarsus, Harran, Kufa, or Tus) wrote his mystical tracts IN CA in the late 8th century. This is complete farce. All the material has been proven to be from much later; and Jabir has been shown to have been a figment of later compilers’ imaginations.

Retro-active attribution of liturgical material (for flagrantly ideological purposes) goes back to the Exilic Period, when the Babylonian scribes insisted–against all verisimilitude–that the Torah was first written by Moses himself (that is: over seven centuries earlier). How is it that Moses was fully apprised of the dialogue between, say, Noah…or Abraham…or Job…and the other characters? As if that were not absurd enough, we are also expected to believe that the Psalms were penned by King David…and that the Song of Solomon and Proverbs were penned by King Solomon…almost four centuries before the Exilic Period.

Alas, credulity knows no bounds when theological agendas are at stake.

In Dar al-Islam, retro-active attribution of authorship has been common practice. Take, for instance, the Ali’d (Shia) “Nahj al-Balaghah” [Peak of Eloquence], the classic treatise traditionally attributed to Ali ibn Abi Talib, the patriarch of Shiism (who lived in the early 7th century). Such attribution is complete farce. Though there were purportedly oblique allusions to (something like) the text starting in the late 9th century, the earliest compilation was (reputedly) done by Abul-Hasan Muhammad ibn Al-Husayn Al-Musawi of Baghdad (a.k.a. “Al-Sharif al-Razi”) c. 1000. (No word yet on why there was still a need to COMPILE the material almost four centuries after it was supposedly written.) This odd historiographical quirk is blithely accepted without further comment.

(But wait. It is even more suspect than just this; for the earliest manuscript of THAT is from the late 12th century.)

Another example of retro-active attribution is the Ali’d book of propitiations known as the “Sahifa [al-Kamilah] al-Sajjadiyya”, which is traditionally associated with the fourth imam: Ali ibn Husayn ibn Ali (grandson of Ali) from the late 7th century. That attribution is farcical as well. There is no record of the book until the 11th century.

If people had been composing (what are purported to be) the most important tracts in history since the 7th century, how is it that not a single manuscript survives in its original form? If such things HAD been composed as the story goes, and so HAD been preserved for posterity during the ensuing centuries, how is it that the ONLY source-material that is currently available was the final product…from hundreds of years after it was ostensibly created? This only makes the least bit of sense if no such manuscript existed in CA until the versions we NOW HAVE finally emerged in the historical record.

In terms of pre-Islamic Arabian poetry, we hear accounts of the so-called Arabian “qasida” [odes]–as with the famous “Banat Su’ad”, written by Ka’b ibn Zuhayr ibn Abi Sulama. It is often claimed that such poetry was composed in “Arabic”; but this is fallacious. (There is an apocryphal tale of Ka’b’s brother, Buzayr, meeting MoM and converting to Islam. Ka’b was eventually executed for heresy.) The earliest version of the “Banat Su’ad” in CA is from the 13th century–written by a Berber poet of the Sanhaja named Al-Busiri (who was also known for his “Qasidat al-Burda”). And it was in the 13th century that the Andalusian poet, Ibn Arabi penned “The Interpreter Of Desires”. Moreover, the so-called “na’at sharif” (encomia to MoM) and “hamd” (encomia to the Abrahamic deity) did not emerge until after CA had (actually) been established.

There are other residual traces of Syriac in general Islamic vernacular. The holiday, Eid al-Adha (from the Semitic lexeme for sacrifice: D[a]-H[a]) is alternately dubbed “Eid al-Kabir”. K-B-R[a] is the Semitic tri-root for “closeness” or “proximity” (with intimations of coveting a source of water). In Syriac, the lexeme was used to refer to “communion”; and—tellingly—is used as such by Syriac Christians to the present day.

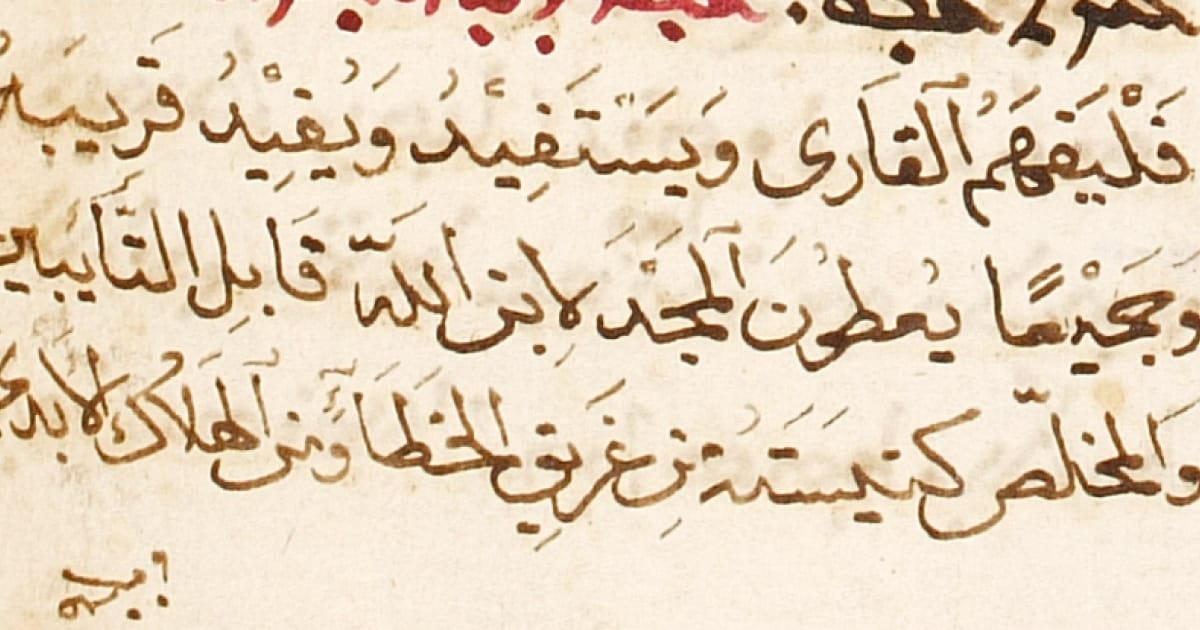

During the Middle Ages, there surely would have been a campaign to systematically destroy Syriac (and other un-approved) versions of the Islamic scripture (esp. the Koran), as such editions of the texts–as we now know–eventually came to be considered an abomination. This would have been roughly analogous to the Nicene Christians’ destruction of non-Canonical texts during the 4th century. (Instead of the issue being objectionable CONTENT, though, the Islamic censure primarily pertained to the coveted scripture being written in an objectionable LANGUAGE.) It is therefore remarkable that we even have the sparse evidence of such early versions that we DO now have. Nevertheless, it is evidence enough to draw the present conclusions.

So what of relevant archeological discoveries? To the present day, there can be little doubt that the House of Saud routinely destroys ANYTHING discovered in the Hijaz that does not fit the desired narrative. (To reiterate: There is–quite literally–no such thing as Saudi archeology.) Indeed, there is only one thing that would happen if a Syriac Koran were to be dug up in Arabia: It would be immediately destroyed; no questions asked. (Syriac Koran? WHAT Syriac Koran?) It is also quite telling that so much development has occurred in Mecca without even the least bit of concern for archeological due diligence. With such extensive digging for the plethora of modern high-rises surrounding the “Majid al-Haram”, NOT A SINGLE ITEM of note has ever been discovered. This is–to put it mildly–outrageous.

It is outrageous UNLESS, that is, there is quite literally nothing to find that would confirm the standard Mohammedan narrative; and a plethora of countervailing evidence.

Undoubtedly, if a liberal regime had ruled over the Hijaz for the last couple centuries, there would now be a wealth of archeological discoveries available–many of which would almost certainly be extremely inconvenient to those who fetishize received wisdom, and have a staunch vested interest in upholding sanctified Islamic lore. This brings to mind the Vatican’s suppression of any and all material that undermines its own version of Christianity’s origins.

The question, then, is not: Why do we not have more evidence of the first incarnations of the “Recitations”? Rather, the question is: Why–after a programatic effort to expurgate Syriac versions of the Koran from the record–do we even have the scant evidence that IS now available? It’s a miracle we have as much as we have; and thank heaven for it. (After all, it’s what has enabled me to write the present essay.)

To reiterate: There is a natural course of memetic genealogy (vis a vis Mohammedan lore) to match the concomitant etymology of CA (as Islam’s liturgical language). This revisionist program operates within the ambit of the same theological heritage–in this case: that of the Abrahamic deity and the various prophets of extant Abrahamic lore. As discussed in the previous essay (on the Syriac-source material for Islamic lore), the cooptation of Syriac tropes into Islamic lore included tales that we now know to be confabulations. (There, I showed how scripture was rife with such tell-tale signs.) This is exactly the sort of thing that we would expect to have occurred in the Middle East during the Dark Ages…or, for that matter, anywhere else at any other point in history.

Indeed, the phenomenon was not unique to the gestation of Mohammedan lore; it’s how things NORMALLY work–irrespective of the era, the region, or the dogmas being promulgated. In other words: There’s nothing special going on here.

We’ve already looked at lexical clues. But there’s more. Upon reading the Koran, we find that there are also residual traces of the original language of the “Recitations” in the PHRASEOLOGY of the text. As it turns out, several verses make more sense in Syriac than they do in CA, indicating that they were likely ORIGINALLY composed in Syriac. One of the most commonly-cited examples of this is 2:135. In CA, it reads: “We believe in the Faith of Abraham the Hanif; and he was not one of the mu-shrik-un.” This is redundant, as a “Hanif” is a monotheist [one who is inclined exclusively toward the Abrahamic deity]; while “mu-shrik-un” means idolaters [those who engage in “shirk”: the worship of entities OTHER THAN the Abrahamic deity]. Meanwhile, in Syriac, the line could be read: “We believe in the Faith of Abraham, who was a heathen YET not one of the idolaters”…which makes more sense. (This is echoed in 3:67.)

One might suppose that the Koran would have read far better in the original Syriac, whereby the raft of redundancies–and grammatical incongruities–with which the book is riddled may have not existed in its original Syriac incarnation.

There also seems to be evidence of residual Syriac prosody–a point made by Günter Lüling in his “On the Pre-Islamic Christian Strophe Poetical Texts in the Koran” [Toward Reconstruction of the Pre-Islamic, Syriac-Christian Strophical Hymnody Undergirding the Transmitted Koranic Verse]. This is just as we’d expect from an oral tradition that originated in an alternate tongue.

The emergence of at least seven Koranic text variants, using different dialects of proto-Arabic (hence the “ahruf”: variations of early Koranic manuscripts) must also be addressed. Had CA already been fully developed (and, for that matter, deemed the eternal, perfect language of god), then the impresarios of the “Recitations” would not have allowed discrepant versions to form. A far more likely explanation for the occurrence of myriad “ahruf” is that CA was still developing from its Syriac antecedent. Due to the fact that this would have invariably been an ad hoc process, it was inevitable that variants would have arisen before one OFFICIAL version would have prevailed. Linguistic metamorphoses are not clean-cut, linear processes. This is especially when the process is limited to oral transmission…over the course of two centuries…amongst highly superstitious men with staunch ideological commitments.

One does not need a PhD in philology (or “comparative linguistics”) to recognize the emergence of CA to be an eminently worldly phenomenon–as with EVERY OTHER CASE of new language formation.

Another question is worth posing: During the transitional period, how did the Ishmaelites THEMSELVES identify the language they were using? Tellingly, the term used for the (Syriac) language in which the first Mohammedan texts were composed was alternately “Suryani[yya]” [Assyrian] and “Nabati[yya]” [Nabataean]. (Assyrians / Aramaeans and Mesopotamians / Chaldeans were both referred to as Nabataeans by early Islamic expositors.) Even more telling, the eldest son of the Mohammedan patriarch, Ishmael (son of Abraham), Nebayoth (who was affiliated with the Assyrians) was often conflated with the moniker, “Nabat[i]” (the ethnonym for the Nabataeans)…thereby revealing (what amounts to) an exogenous perception of ethnic origins. That Ishmael was (implicitly) referred to as Nabataean by the pre-Islamic Ishmaelites is, to put it mildly, extremely revealing. It reveals that they saw themselves (qua Ishmaelites) as inheritors of a Nabataean LINGUISTIC legacy. (It certainly was not the religious or political legacy that they were embracing!)

Are there other clues? Let’s look at city names. It is telling that during the Rashidun period, when the Mohammedans conquered the Byzantine city of Germanikeia [Caesarea] (located in the frontier zone known as “Al-Awasim”; i.e. Cilicia) c. 645, they re-christened it “Mar’ash”–which was a SYRIAC name. And instead of the Byzantine “Capitolias”, the conquering Arabs opted for the Syriac moniker (“Bet Reisha”), dubbing it “Beyt Rash”.

This also happened when they conquered the ancient Armenian city of Tigranakert in Cappadocia (named after Tigranes the Great; corresponding with the present-day Silvan). At the time, the city was referred to as “Martyropolis” by the Byzantines (a Greek moniker), yet it was referred to as “Mayperqit” in Syriac by–well–those who used Syriac. Sure enough: The Ishmaelites re-christened the city “Mayfarqin”.

These were not aberrations. For the same happened with Edessa. The Mohammedans referred to it not by its (Seleucid) Greek name, but instead as “Ar-Ruha” [alt. “Urfa”], a variant of its Syriac name: “Urhay”. When the Arabs established the “city of mosques” in Mesopotamia, they derived its name (“Fallujah”) from the (Palmyrene) Syriac, “Pallgutha” rather than referring to it by its historical name: “Nehardea” (which was located near the place that had been known in previous centuries for is famed Judaic academy: referred to in Aramaic as “Pumbedita”).

And when the the Arabs conquered the Sassanian-held “Peroz-Shapur”, the city was re-named “Anbar”: Middle Persian for “granary” / “storehouse”. If the conquerers were seeking to strip the city of its Persian pedigree by re-naming it, then why would they have opted to use a Pahlavi term? This only makes sense if, at the time, they did not have their own UNIQUE language to use (that is: if they did not yet have a CA term of which to avail themselves). If Arabic had already been the go-to language, and they wanted to refer to the place as “granary”, then Anbar would now be called “Makhzin”.

Something similar happened with monikers for Mesopotamia. The Old Aramaic “Erech” was based on the Sumerian “Uruk” (named after the Bronze Age city). “Erech” would later be the basis for both the Avestan and Syriac synecdoche for the region: “Eraq”. That eventually led to the Arabic moniker “Iraq” (subsequently used for the name of the modern nation-State). Bagh-dad was founded on the site of a Syriac-speaking, Nabataean settlement; in the vicinity of the old Persian city of Ctesiphon.

Were all these instances aberrations? Nope. Here are ten more place-names that illustrate the scope of Syriac influence in the medieval Arab world:

- “Yemen” comes from the Syriac for “place of strength”

- “Ajman” comes from the Syriac for “place of sadness”

- “Dubai” comes from the Syriac for “pleasant place”

- “Sharika” comes from the Syriac for “shining [place]”: “shraga”

- “Riyadh” comes from the Syriac for “excellent [place]”: “riath”

- “Basra” (founded c. 636) comes from the Syriac for “settlement”: “basratha”

- “Najran” comes from the Syriac “Nagrano”

- “Kuwait” comes from the Syriac “Koioto”

- “Bahrain” comes from the Syriac “Beth Nahrain”

- “Qatar” comes from the Syriac “[Beth] Katroie”

And instead of the prevalent monikers of the time, “Khalpe” / “Khalibon” or “Beroea”, the Mohammedans referred to the city of Aleppo by its Syriac moniker: “Halab”. Also note the Syriac word for “elevated”: “ram”. This lexeme was used in “Ram-Allah”: a city in the highlands north of Jerusalem, possibly corresponding to the Samaritan “Beiroth[ah]” (rendering it “elevated god”). Alternately, “ram” was used for “thunder”. Thus Ram-Allah could have been a variant of the Syriac “Ram-ilah” (thunder god), which would share an etymology with the Hebraic “Ram-i-El” (thunder of god).

“Ram” was also used for the Galilean town of “Al-Ram[a]”. Caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik then founded “Ram-la” c. 715 (replacing Lydda as the provincial capital of Palestine), though the exact etymology of that name remains somewhat of a conundrum.

Generally speaking, there is nothing remarkable about the derivative nature of place-names; but this particular etymology reminds us that CA typography–and CA onomastics in general–was just as contingent as was any other language’s onomastic convention. Islam’s liturgical language was an accident of history, nothing more.

In sum: CA did not originate in Arabia. Accordingly, the moniker “Iraq” for Mesopotamia did not have its origins in Old South Arabian; it had its origins in Persian and/or the antecedent NORTH Semitic tongue: (Nabataean) Syriac.

Note that the distinction between Nabatean Aramaic and Nabatean Arabic (both are Syriac) is like that between, say, puma and cougar (both are mountain lions). This misleading linguistic taxonomy was coined to elide the fact that the primary language of the Arabs from the 1st through 8th centuries (in, say, Edessa, Palmyra, Petra, and Nessana) was a derivative of Aramaic (with bits of Old North Arabian thrown in when one ventures as far south as Hegra and Dumah). “Arabic” did not yet exist as a distinct language. The Arabs of the region spoke one or another form of Syriac and/or Old North Arabian (a descendant of Dedanic). Another distinction without a difference is “Koranic Arabic” vs. “Classical Arabic”: basically two different ways of thinking about the liturgical language of Islam, which—as we’ve seen—was developed starting in the last decade of the 7th century. (One may as well say “H2O” as opposed to “water”.) {53}

To the extent that people said / did things that Syriac-speaking would have said / done (and NOT what CA-speaking people would have said / done), it is reasonable to conclude–barring any as-yet-unknown factors–that they spoke Syriac (rather than CA).

Koranic onomastics provides EVEN MORE examples. In the Koran’s account of the Great Flood, Mount Ararat (the Greek and Hebrew renderings of “Urartu”; though the mountain itself was referred to by the ancient Greeks as “Nibaros”) is rendered “Gudi”. From whence might this alternate name have come? As it turns out, it is a variation on the Syriac version of the moniker, “Kardu”–an appellation that was used as late as the 10th-century in Dar al-Islam (as attested by Islamic historian, Al-Masudi in his “Meadows Of Gold And Mines Of Gems”). This only makes sense if the early expositors of Islamic lore were using Syriac. (The Kurdish moniker, “Agiri”, is yet another variation of the original Urartian moniker.)

And so it went: During the 7th and 8th centuries, the Ishmaelites used Syriac onomastics when staking their claim on newly-conquered places. Once we consider this, a question arises: If Muslims were already speaking CA, then why was it that distinctly Syriac monikers were routinely used?

The evidence attests to the fact that during MoM’s lifetime, virtually EVERYONE was using Syriac, and that the emergence of CA (as a fully-developed language) was still quite a ways off. The existence of sporadic inscriptions in proto-CA during the intervening time (i.e. prior to the 9th century) attests to the long gestation period of the new language. Such inscriptions are NOT evidence for its existence as a lingua franca at the time. Rather, they are evidence that CA was not concocted ex nihilo, but existed in embryonic form…in isolated instances. {2}

Tellingly, when a chronicler in the region opted to compose a chronicle of the events surrounding the Lakhmids in the late 6th and early 7th centuries (i.e. when MoM was purportedly conducting his ministry), he opted to do so IN SYRIAC–producing what we now refer to as the “Khuzistan Chronicle”. That was in eastern Arabia–much farther from the Levant than was the Hijaz. Clearly, Syriac was in wide use; and was the go-to language for expositors across the region at the time.

In the 8th century, Ali ibn Hamid ibn Abi Bakr of Kufa wrote his chronicle about the Umayyad conquests in Sindh: the “Chach Nama”. Tellingly, he wrote it in Pahlavi (Persian), not in CA. Note that the author was from Mesopotamia; and even hailed from the city in which the EARLIEST SCRIPT (Kufic) of proto-CA emerged. If ANYONE would have been apt to use CA at the time, it would have been him. Yet he didn’t. There is no other explanation for this than that CA did not yet exist as a literary language in Dar al-Islam.

In the late 8th / early 9th century, Patriarch Timothy II of Baghdad was still using Syriac–even in his writings that were not liturgical. And across Eurasia at the time, the Sogdians (impresarios of the Silk Road) were still using Syriac script…which means that it was still the most useful language for merchants who were trading with the Ishmaelites. There is no mention of having to use some distinctly “Arabic” language. {72}

So it came to pass: Throughout the Middle East, Syriac (using various Hijazi scripts enumerated in footnote 2) would eventually be transplanted by its linguistic descendent (CA) during the late 8th / early 9th century. THAT is when the metamorphosis of CA was reaching culmination (as Islam’s liturgical language). This tells us that the development of Mohammedan scripture and the development of CA were coeval–that is: aspects of the same process (a process that occurred long after MoM had come and gone).

It should come as no surprise, then, that the earliest texts in fully-developed CA do not occur until the 9th century. And EVEN THEN, some texts continued to be composed in Syriac–as with the writings of Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi of Al-Hirah, Ishodad of Merv, and Theodore Abu Qurrah of Edessa. This would not have made sense had CA been the prevalent language ALL ALONG.

Non-Muslims–living as “dhimmis” within the Islamic dominion–were ALSO still writing in Syriac on through the 9th century. This is an eventuality that would be difficult to square with the fact that the lingua franca of the region had already been CA for over two centuries. After all, dhimmis were subordinates to the established order, and so would have been obliged to defer to the preferred language of their rulers…ESPECIALLY if they were disseminating material that was meant for a general audience.

Even during the Islamic “Golden Age”, Syriac was STILL being used in the Muslim world–even if not by Muslims (for whom it was, by then, an eschewed language). For example:

- Theodore[t] bar Kon[a]i of Beth Garmai (modern Kirkuk) composed his “Scholion” in Syriac c. 792.

- Assyrian patriarch, Thomas of Marga [a.k.a. “the Great Zab”] composed “The Book of Governors” in the 9th century. {30}

- Eliya bar Shinaya of Bet[h] Nuhadra [a.k.a. “Elijah of Nisibis”] composed works in Syriac in the late 10th / early 11th century.

- Nestorian author, Elijah of Nisibis / Adiabene (Mesopotamia) composed his great chronicle in the 11th century.

- Jacobite author, Michael of Miletene (central Anatolia) composed his great chronicle in the 12th century.

The “response literature” (re: the Babylonian Talmud) coming from the great Talmudic Academies of Mesopotamia was primarily written IN SYRIAC from the 8th thru 10th centuries.

In the late 8th and early 9th century, the Patriarch of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, Timotheos of Adiabene conducted all of his correspondences with Muslim leaders—including the caliph in Baghdad—IN SYRIAC. This was also the case with Theodoros Abu Qurra.

In the 9th century, we might also note [Habib ibn Khidma] Abu Raita of Tikrit, Ammar of Basra, and Nonos of Nisibis. Another notable Syriac work was the “Zuknin Chronicle” by Dionysius of Tel Mahre. Meanwhile, the great Muslim polymath, Al-Kindi (from Kufa) was a patron of the Syriac thinker, Hunayn ibn Ishaq (from Hir[t]a). What were they interested in doing? Translating the great Greek and Persian into Syriac…and then Arabic.

Works like the “Chronicle of Sireth” [alt. “Siirt”] by Ishodnah of Basra, were eventually rendered in CA. We know that it was RE-written because, in its latest version, its accounts were given a flagrantly pro-Islamic bent…when, obviously, the original would have exhibited no such partiality. The updated version is infused with Muslim triumphalism and flagrant anti-Zoroastrian bias–something the original author would have never countenanced.

Granted, Syriac was the Nestorians’ liturgical language, so the fact that such chronicles were composed in Syriac isn’t all that startling. However, these were HISTORIES (i.e. books written for a wider audience), not liturgical texts (intended only for clergy). So there was no pressing reason to have used Syriac…if, that is, it were not also (still) the lingua franca of significant swaths of the Middle East. It is telling that such prominent works were only rendered in Arabic much later.

In the early 10th century, the Nestorian philosopher, Abu Bishr Matta ibn Yunus of Baghdad (affiliated with the monastery of Dayr Qunna) was the teacher of the great Muslim philosopher, Abu Nasr al-Farabi. The great Syriac thinker, [Abu Zakariya] Yahya ibn Adi, in turn, studied under al-Farabi. And HIS student, a Syriac Christian named Abu Ali Isa ibn Ishaq ibn Zura was a prominent teacher in Baghdad into the early 11th century. By that time, interlocutors were using medieval variants of BOTH Syriac and Arabic.

In the early 11th century, the Syriac thinker, Eliya of Nisibis (Adiabene) was renown for his discussions with the Hamdanid vizier, Abu al-Qasim al-Husayn ibn Ali al-Maghribi of Aleppo. The two men were conversant in Syriac and Arabic…something akin to, say, Dante being conversant in both Florentine / Tuscan and Vulgar Lain.

In the 12th century, Jacob bar Salibi of Amida / Melid[u] (a.k.a. “Dionysius”) wrote Syriac commentaries on the Melkites and Mohammedans. Indeed, Syriac writers continued to write about Islam into the High Middle Ages. The Chronicle of Michael Rabo (12th century) and the Chronicle of 1234 (both of which were based on the work of earlier chroniclers like Dionysios of Tel Mahre) include accounts of MoM and of the Mohammedan creed. (Also notable was apocalyptic Syriac material like the legend of “Sargis Bhira”, which would—of course—later be rendered in medieval Arabic and incorporated into Islamic lore.)

In the 13th century, the famed Syriac bishop, Mar Gregorios bar [h]Ebraya of Malatya (a.k.a. “Gregory bar Hebraeus”) produced an extensive corpus of material. He is most known for the theological commentary, “Awsar Raze” [Storehouse of Secrets]; the chronicle, “Makhtbha-nuth Zabhne”; and the memoir, “Menarath Kudhshe” [Lamp of the Sanctuary], which was later summarized as the “Kethabha dhe-Zalge” [Book of Rays]. “Mar” Odisho [alt. “Abdisho”] bar Berika of Nisibis wrote Syriac commentaries on the Bible in the late 13th / early 14th century. {58}

Interestingly, many of these works were given the imprimatur of the Abbasid caliphate. The issue was never raised that they’d been composed in some foreign–let alone un-approved–language. After all, they were being composed in the language that Dar al-Islam had originally used.

To reiterate: CA’s germination was, in many ways, concomitant with the development–and codification–of the Mohammedan creed. This makes sense, as linguistic co-optation often tracks with prevailing memes whenever cultures transform.

Also telling: During the early Middle Ages, we find that SYRIAC was the linguistic substrate of each and every Arabic “am[m]iy[y]a”. The Arabic dialect of the Maghreb emerged from Syriac interacting with Berber. In Egypt, it was from Syriac interacting with Coptic. In Arabia, it was from Syriac interacting with Old Arabian. CA is simply a snap-shot of the language as it came to be in the Levant during the 8th century—effectively frozen in time during the course of its metamorphosis. This is not unique; as it is typically done pursuant to the creation of liturgical languages—be it Classical Arabic, Vedic Sanskrit, Koine Greek, or Vulgar Latin. In each case, after it forms, a sanctified version of the language is—effectively—fossilized. {65}

After such a snap-shot, the demotic language invariably continues to undergo a metamorphosis—eventually yielding an array of later versions. And so it goes: From Vedic Sanskrit, we now have modern Hindustani…as well as Gujarati, Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam, and a potpourri of other Indian tongues. From Koine Greek (common Attic), we now have “Nea [h]Ellinika”. From Vulgar Latin, we now have a wide assortment of Romance languages—from Galician to Romanian. The ramification of Arabic has been just as extensive—from Moroccan to Hadhrami. {66}

Tellingly, even the Maghrebi script was derived directly from the Kufic script. In other words, it is an alternate branch of the script’s evolution into the CA script. The branching THERE seems to have happened in Tunisia in the 9th or 10th century; which means that—even then—Kufic was STILL the source-script for creating novel scripts.

Unsurprisingly, the Syriac substrate of the language is most palpable in its Mesopotamian version—coalescing, as it did, around Syriac hubs like Damascus, Harran, and Edessa…and later, the caliphate’s first capital: Kufa. {73} The medieval Arabic of the Middle East would have more overtly exhibited its Syriac roots but for a series of linguistic infusions in the intervening centuries—notably, of Oghuz Turkic from the Seljuks in the 11th century, of Mongolian from the Il-khanate in the 13th century, and of (more) Middle Persian from the Safavids in the 16th century. {71}

It might also be noted that it is not uncommon for people to be completely unaware that some of the morphemes in their spoken tongue–even some of the most common and important–came from another language. The best example of this is the term for “tempura” in Nihon-go (Japanese language). As it happens, the word is derived from a Portuguese culinary term. This was due to the prevalence of traders from Portugal during the 16th century (esp. at Nagasaki). Unsurprisingly, few Nihon-jin (Japanese people) today are aware of the fact that they are uttering something derived from Europeans when they refer to the fried vegetables so often found in their cuisine. This is, of course, an isolated term in the vast Japanese lexicon; but it illustrates how quickly etymologies can be forgotten, and foreign lexemes reified. Of course, there is little motivation to elide the fact that items in a bento box have a “Western” name; yet this fact is nevertheless unknown.

(Surprisingly, there is no etymological relation between the respective terms for “thank you”: “arigato” and “obrigado”…in spite of the fact that they are morphologically similar.)

Another example is the (non-Germanic) Occidental lexeme for god…which actually originated with the Sanskrit term, “Dyaus-pitah”. That was rendered “Dyeus” in the Indo-Greek vernacular…which was rendered “Dios” (of which a variant is “Zeus”) in the Hellenic vernacular. That was eventually rendered “Deus” in Latin. When it comes to the Romance languages (and Tagalog), the rest was history. (English now uses the Frankish lexeme, which was based on the Old Saxon “gott”.)

It is commonplace for English-speakers to forget how many of their words originated in Greece, Arab lands, Persia, and even India. And very few are aware that “tornado” (a term for a severe Caribbean storm) is derived from an indigenous Puerto Rican language. Such myopia becomes even more pronounced when something is sanctified. For NOBODY wants to concede that their own language–let alone their liturgical language–is derivative (i.e. just another accident of history). When it comes to CA, such a concession would bely its purported timelessness. Surely, the Creator of the Universe did not adopt his own tongue from the Nabateans!

So what does the (final version of) the Koran ITSELF say about CA? Islam’s holy book seems to contradict the claim that CA is god’s language–and thus the ideal language by which his revelations are revealed–by being so clumsily written and haphazardly formatted. Much of the book betrays its Syriac origins–not only with its lexicon, but with its CONTENT (as adumbrated in the previous essay, on Syriac source-material).

Let’s look at a pertinent example. 16:36 and 35:24 say that the Abrahamic deity had already sent a prophet to every nation…EXCEPT Arabia, where MoM was the first prophet sent, per 6:155-157, 32:3, 34:44, and 36:2-6 (even though ALL THAT contradicts the supposition that Abraham and Ishmael dwelled in Mecca). Here’s where the issue becomes even more interesting. In 42:7, the Koran’s protagonist declares that–after all those other revelations to all those other nations–he sent a “Qur’an Arabiyyan” to the Arabians. Why? So that the revelations may finally be relayed to the “mother of settlements” in a language that they would be sure to understand.

A Koran of the Arabs, you say? This is a rather peculiar specification to make about a book that, we are told, COULD ONLY POSSIBLY BE in Arabic: the native language of the Creator of the Universe. The CA rendering was a special measure taken to cater to the intended audience (the Ishmaelites), not the result of a timeless language that the Arabs just so happened to stumble upon.

Also note that, in order for the (ostensibly) “Arabic” Koran to have been eternal, we are expected to believe that the evolution of Semitic languages meandered for THOUSANDS of years–incorporating sporadic Persian terms along the way–before finally, at long last, arriving its pre-ordained linguistic destination. In other words: This particular linguistic lineage took millennia before eventually developing into a language that had existed in heaven all along. (So Phoenician, Samaritan, and Aramaic were just a means to THAT END.) Why the extraordinarily long delay? God only knows.

46:12 then goes on to stipulate that the Final Revelation confirms previous revelations IN ARABIC–as if this were a new development. Such comments indicate that CA was an adaptation (developed for a specific audience), rather than a timeless language. According to this narrative, a version of the “Revelations” was rendered IN CA for a newly-defined group of people: the (newly Mohammedan) Ishmaelites. This declamation comes off as special pleading. Such appeals are far more incriminating than they are validating–a lesson given to us by Gertrude in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”. (I address this pleading in the previous essay: “Syriac Source-Material For Islam’s Holy Book”.)

Alas, merely broaching such matters is off-limits for even the most open-minded Islamic apologists. A personal anecdote illustrates this point:

I once spent time with an affable scholar of Islamic scripture. A devout Saudi from Jeddah, he was a “hafiz” who was fluent in CA and had read EVERY PAGE of all the major Hadith collections. Suffice to say: He was incredibly knowledgable. Fortuitously, he was eager to talk with a “kafir” (me) who showed sincere curiosity in the nuts and bolds of his Faith, and in the history of the religion. During the course of our lengthy conversations, he seemed quite open-minded, and exhibited a strikingly liberal attitude with respect to pluralism. However, the moment that I implied that Bukhari’s and Muslim’s Hadith MIGHT have initially been composed in Pahlavi (that is: in something other than Islam’s liturgical language), he became ornery. Inconceivable! From an amicable disposition (whereby he countenanced cosmopolitan ideals), he instantly transitioned to a posture of obdurate revanchism (whereby all he could muster was a harrumph). This was yet another reminder that mental acuity goes out the window whenever something is fetishized. (Delusion is symbiotic with obsession.)

Lord knows what paroxysms of vexation this gentleman may have undergone had I insisted the Koran was originally composed in Syriac. He would have surely become apoplectic had I broached the present matter. {35} For the very insinuation of this (indubitable) fact is currently unheard of in the Muslim world. There can be no discussion of such a thing. Ever. Period.

When dealing with Reactionaries, unwelcome truths are invariably met with consternation rather than open-mindedness. The mere suggestion that the “Final Revelation” was composed in Syriac by fallible men (and compiled after the purported “Seal of the Prophets” is said to have lived) is beyond the pale in most Muslim precincts. This is a problem. It is especially a problem for those seeking to come to terms with history; and who deign to find solid ground on which robust Reform can proceed.

To reiterate the point: Had the complete Koran been rendered in fully-developed CA since day one (i.e. since the caliph, Uthman allegedly commissioned its compilation), the archeological record would be OVERFLOWING with manuscripts. That is to say: There would be oodles of carefully-preserved Korans throughout the Muslim world that date from the late 7th century. As we have seen, there is literally NOT ONE in existence. Pray tell: What could have possibly accounted for the hold-up? The present thesis provides the obvious explanation.

This is a touchy subject. After all, conceding the “Recitations” were originally in Syriac means conceding that Islam’s holy book is not timeless. For–like any other holy book–it is a historical artifact; and must be treated as such. Once we consider the timeline of CA’s emergence in the literary record, we find that the book’s genesis post-dates the genesis of the Mohammedan creed. This would have occurred during a period when Syriac was the lingua franca of most of the Middle East–from Sinai to Chaldea, from Al-Sham to the Hijaz.

And once we consider the slew of Syriac lexemes with which Islam’s holy book is festooned, it is hard to ignore the fact that its verses were originally composed in Syriac. It is no surprise, then, that the esteemed scholar, Alphonse Mingana surmised that an aptitude in Syriac was the key to understanding the Koran. {36}

CONCLUDING REMARKS:

The Story Of Ahikar is a case study in how religionists tend to go awry when it comes to positing the origins of their scripture. The tale was originally composed in Aramaic in the 6th century B.C., and proliferated during Classical Antiquity. During Late Antiquity, it primarily circulated in Syriac—whereby the protagonist’s name was rendered “Haikar”. This seems to have happened via the (Syriac) Book of Tobit and/or the (Persian) Story of Sandbad the Sage, wherein he is described as a wise man. {55}

The tale was translated into Classical Hebrew, Koine Greek, Old Armenian, and Middle Persian; then into medieval Arabic, Old Slavic, Old Turkic, and Ethiopic—during the Middle Ages. It eventually made an appearance in the super-popular “Arabian Nights” anthology. “Ahikar the wise” thus became “Haikar al-Hakeem”. And when the legendary figure finally made his way into Mohammedan lore, his name was rendered “Luqman al-Hakeem” (as found in Surah 31 of the Koran). {56}

Proverbs attributed the folkloric Arab hero, Luqman bear a remarkable resemblance to those of the fabled Ahikar. A couple are worth noting:

First: “The eye of man is as a fountain, and it will never be satisfied with wealth until it is filled with dust.”

Second: “O my son, bow your head low, soften your voice, be courteous, walk in the straight path, and be not foolish. Don’t raise your voice when you laugh, for were it by a loud voice that a house was built, the ass would build many houses each day.”

Both excerpts are almost a verbatim facsimile of antecedent (non-Abrahamic) lore. Thereafter, the impression throughout Dar al-Islam was that the tale stemmed from Ishmaelite sources.

In assaying this development, it’s worth recalling the Mohammedan agenda to destroy the oldest (Syriac) material it used during its earliest stages of development. Had this duplicitous endeavor been successful with regard to the Story of Ahikar, the earliest copies we would now have would be in CA. Consequently, some would suppose that it had originally been an Arabic work. Under such circumstances, such a (false) supposition would seem to be justified because MODERN Syriac versions of the book (that is: those rendered in Chaldean Syriac) were actually derived from medieval Arabic versions.

Felicitously, the early (Classical Syriac) manuscripts survived due to having been preserved in Jewish caches. So we know that the Mohammedans lifted the tale from Syriac sources, not the other way around.

Ask people of any religious tradition in which language their own scripture was originally composed, and many will not know the answer. The Hebrew Bible was originally composed in Babylonian Aramaic. So we can be forgiven for snickering when Jewish mystics engage in “gematria” (looking for secret codes embedded in the Hebrew rendering of the text)…as if there was a divine message hidden in the sequence of Hebrew letters.

The earliest copies of the New Testament books were ABOUT those who spoke Aramaic, and were composed in Koine Greek. So we can be forgiven for snickering when clergy in the Roman Catholic Church recite the liturgy in Latin…as if there was something preternatural about that tongue.

The thing about liturgical languages: proponents ascribe to them a beguiling cosmic significance based on a mis-understanding of history–a mis-understanding that is as self-ingratiating as it is self-serving. The same goes for those who fetishize Classical Arabic. One may as well suppose that the King James version of the Bible is a carbon copy of the text’s earliest form. In reality, it was a translation–into a florid style of English–that was done in 1604-11; which was based largely on research that had been conducted a half century earlier for the Geneva Bible…which had been roughly based on Koine Greek manuscripts…which had presumably translated with perfect accuracy the ARAMAIC spoken by the original Palestinian sources. Yet the way Baptists and Pentecostals treat this 17th-century edition of their scripture, one would think they were quoting verbiage straight from god’s mouth. Such delusive thinking is typical. (Laughably, the ancient Palestinian name, “Yehoshua” was revamped into a magnificently Anglo-Saxon “Jesus”; and votaries never looked back.)

We should not be surprised by this kind of errancy, as we all like to think that, whenever we cite from a favored source (often, to justify our position on an important matter), the citation is iron-clad. If a source is deemed sacrosanct, we ardently want to believe that we are citing its most authentic version. This is, after all, what makes our position seem unimpeachable; and the diktats found within sacred texts seem inviolable.

The resulting impression is as follows: “It’s our liturgical language; so the material we’ve designated was composed in that language from the beginning.” In other words: If we prefer scripture in a certain language, then we are inclined to suppose that it must have been in that language ALL ALONG. Otherwise, we’ve consecrated something that is derivative, thereby bringing into question the credence of our sacred doctrine. So the illusion has tremendous utility.

Such a spurious claim is made all the more imperative when the idea is that one’s holy book is a verbatim transcript of god’s speech (inscribed on celestial tablets when the universe was first created). To concede that the account of “Luqman al-Hakeem” in Surah 31 is just a take-off on antecedent lore would be to concede the derivative nature of Islam’s holy book. To acknowledge that the Koranic passage is just a regurgitation of the tale of Ahikar the Wise from the (Syriac) Book of Tobit and/or the (Persian) Story of Sandbad the Sage would be to effectively nullify the entire rational for fetishizing CA.

In closing, we might note that this thesis would be very easy to disprove. All it would take is a SINGLE manuscript of a complete Koran–or the manuscript of ANYTHING–composed in fully-developed CA that can be conclusively dated to the late 7th century (e.g. during Uthman’s reign). If the Koran had ALWAYS existed in CA, and had not been rendered in ANYTHING BUT CA for the generation or two after MoM’s ignominious death, then SURELY there would be such a codex somewhere. This would be especially likely considering the fact that THAT BOOK was considered the most valuable text in the entire universe…by one of the world’s most powerful empires (Umayyad, then Abbasid) at the time. And, if we are to believe the legends, the Creator of the Universe would have INSISTED it be preserved for posterity. {57}

That no such artifact has ever been found is either dumfounding…or it is overwhelming proof that no such book existed during that time. Given what we know about the history of Syriac in the region, there is no reason for us to be dumfounded.