The Forgotten Diaspora (1)

February 3, 2023 Category: Uncategorized

LANGUAGE:

For Ashkenazim, “Yiddish” originally referred to “leshon Ashkenaz” (alt. “loshn Ashkenaz”), which was generally taken to mean “language of the foreigner”—that is to say: the language spoken in the place that came to be dubbed “Ashkenaz”: a toponym based on the new ethnonym of those foreign (Turkic) Jews. This term for the Turkic Jews’ strange language was in contradistinction to “loshn-koydesh” [sacred vernacular; i.e. medieval Hebrew]. Later, the new tongue would be referred to as “Yiddish-Taytsh”, roughly meaning “Jewish semiotic” (effectively a Judaic creolization of Turkic, Slavic, and Germanic). NONE of this would have made sense for formerly Sephardic people who deigned to adopt a new dialect. Yet…in light of the present thesis, it makes perfect sense.

None other than Rashi himself used this nomenclature in his Zarfatic writings. This indicates that–UNLIKE Ashkenazi Jews–he saw the Germanic tongue as categorically foreign. Tellingly, the same epithet was also used by Mizra[c]hi (Palestinian) Jews to refer to the attacking Crusaders. (!) Rashi was clearly not a progenitor of the Jewish people who embraced the Germanic tongue (i.e. the soon-to-be “Ashkenazim”). For him, “Ashkenaz” was a pejorative for THE OTHER. He would not have referred to fellow Sephardim in this manner, even if they were seen as a divergent sect. This only makes sense if he saw that Jewish community as foreign.

To further assess the credence of the present thesis, it is helpful to evaluate linguistic developments. Throughout the region-in-question (including what came to be known as the “Pale of Settlement”, stretching from Lithuania down to Volhynia), many Jews came to speak a Judaic derivative of High German: Yiddish–a language that has no Semitic roots. {31}

The etymology of “Yid[d]ish” is itself quite telling. It is a variation on “Yehud[i]” with the suffix “-ish” appended. So it is simply an alternate way to say “Jewish”. This indicates that it was thought of primarily as a language for Jewish people—a peculiar way to think of a language; for, as we will see, other Judaic creole tongues were referred to according to the country / ethnicity with which they were associated.

There are other insights we might glean from the nomenclature. “Yid[d]ish” is sometimes used as a modifier for “Taytsh” [alt. “Taitsh”], which is an Ashkenazic colloquialism for “German”. This word choice is revealing, as “taytsh” actually means “translation” (as in “fartaytshn”). Hence “Yid[d]ish Taytsh” is taken to mean “Judeo-German”, yet literally means “Judaic translation”. Also revealing is the term “ivre taytsh” [translation of Hebrew], which was used to refer to Yiddish renderings / explanations of Hebrew texts. Descendants of Sephardim would not be inclined to refer to such texts in this way, nor would they be inclined to treat such material as foreign. This indicates that, when Yiddish emerged as a new tongue, the Ashkenazim had only recently come to Hebrew texts. (Again, they were likely acquainted with Jewish scripture in Aramaic / Syriac, and possibly Sogdian.)

So what of Old Turkic? A preliminary point to make: Turk-IC is not the same as Turk-ISH. The Turkish language is based on the Oghuz line of Old Turkic, brought to Anatolia by the Seljuk Turks in the 11th century; and eventually adopted by their descendants, the Ottoman Turks as a lingua franca. (Other Oghuz languages include Gagauz and Azeri.) This is to be contrasted to the Old Uyghur line, spoken by the Tatar / Oghuric peoples of the Eurasian Steppes, which led to the Kipchak family of tongues. The [k]Hazarian diaspora would never have ventured through Anatolia (that is: down through the southern Caucuses and Armenia, and subsequently into the lands south of the Black Sea). Therefore any theory that Yiddish somehow originated in Anatolia is spurious. In any case, what we now refer to as “Turkish” did not exist c. 1000. (The Seljuks hailed from central Asia; and thereafter moved westward.) Ottoman Turkish developed from the Oghuz branch of Old Turkic. (The Oghuz who remained behind now speak Turkmen.) More to the point: The Ottomans did not establish themselves AS SUCH until three centuries later; whereupon they asserted a “Turk-ISH” identity (to wit: Ottoman Turks). For more on this topic, see the work of linguist, Paul Wexler; as well as insights from geneticist, Eran El- Haik. {69} {71}

Wexler hypothesizes that Yiddish has primarily Slavic (esp. Sorbian)–and even Persian–rather than Germanic roots. The present thesis does NOT depend on that being the case. Wexler also hypothesizes that Ashkenazim had Slavic–and even Caucasian–ancestral origins (in addition to their Turkic origins); though he erroneously conjectures that this may have had something to do with Anatolian influences. (It is highly unlikely that the [k]Hazarian diaspora ended up in Anatolia–that is: where Turk-ISH people ended up.) One way or another, Wexler’s hypothesis would not affect the conclusions drawn here.

Suffice to say: Some Slavic influences would be unsurprising considering the conquests of Svyatoslav Igorevich and his heirs–which invariably would have precipitated some intermixture of Turkic peoples with the (Slavic) Kieven Rus. After all, pursuant to ANY conquest, miscegenation invariably ensues. It should be noted that various Turkic peoples still live in the upper Caucuses EVEN TODAY–as with the Balkar, Karachay, Kalmyk, Kumyk, Ghalghai (Ingush), and Nakh peoples. Others in the area (notably: the Adyghe / Circassians) came to be ethnically mixed (Caucasian, Bulgar, Tatar, Slavic, Arab, and Turkish). Most ended up converting to either Islam or Christianity.

It is important to rectify any confusion about the linguistic genealogy of the different Turkic branches; as the ramification of languages was a bit convoluted during most of the Middle Ages. The [k]Hazarian diaspora would have spoken a tongue from the Oghuric branch of Old Turkic (shared by the Bashkirs and Sabirs); while “Tatars” (a vague term for various Turkic peoples—from the Avars and Bulgars to the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz / [k]Hakas) spoke variants of Kipchak-Kumen. This taxonomy is misleading; as those languages were ALL likely of the same lineage—a fact demonstrated by the Chuvash (an Oghuric Turkic people related to the Volga Tatars) and the Kumyks (who, like Karaite Jews, still speak a Kipchak-Kumen language). In a sense, then, ALL Turkic peoples of the Eurasian Steppes were “Tatars”; and there was not a fundamental difference between the Oghuric and Kipchak-Kumen linguistic branches during the Middle Ages. {91}

So which Turkic peoples STILL LIVE in the former [k]Hazaria? The Kalmyks. As it happens, “Kalmyk” means “Remnant” in the local vernacular. These were among the Turkic peoples of the northern Caucuses known in the Middle Ages as the “[Vai-]Nakh”. Eventually, the indigenous Turkic population combined with a Mongolic people (Oirats) who had migrated from Dzungaria (near the Tamim Basin) in the 1620’s. Upon their arrival in the northern Caucuses (a process that culminated c. 1630 in what was, at the time, the Turkic Astrakhan Khanate), the Oirats seized power. Consequently, the (gentrified) Kalmyk population transitioned from Tengri-ism to Tibetan Buddhism (that is: the Faith that was endemic to Dzungaria). That new regime ruled over Astrakhan, Kalmykia, and Dagestan—that is: the northern Caucuses—in what used to be central [k]Hazaria. (Note: Many Kalmyks—specifically those who identified more with their Oirat heritage—ended up migrating back east to Dzungaria in the 18th century in order to evade Tsarist oppression.) To the present day, the Kalmyks of the northern Caucuses trace some of their language, sartorial practices, cuisine, and folklore back to the [k]Hazars. {109} Meanwhile, the Circassians were sometimes referred to as the “Kashak” in ancient sources; meaning that those who now speak “Kabardian” and “Adyghe” are remnants of their diaspora.

Note that another Turko-Mongolic people who still live in the region are the Nogais. This is an ethnic group that characterized both the Crimean and Astrakhan Khanates. Jews who remained in the region—known as “Kavkazi”—speak a hybrid of (Turkic) Azeri and (Persian) Judeo-Tat (alt. Juhuri / Juvuro), the latter of which was itself a hybrid of Aramaic and Middle Persian.

To fully understand how Old Turkic evolved into the variety of modern Turkic tongues, it is important to understand the fundamental difference between the two major lineages: Oghuric and Oghuz. This distinction shows why it is misguided to try to find similarities between Old Yiddish and, say, Ottoman Turkish. {92}

The Oghuric speakers never ventured south of the Caucuses mountains, and certainly never lived in Anatolia. In the 10th century, the Persian traveler, Abu Ishak al-Farsi of Istakhr (a.k.a. “Al-Istakh[a]ri”) noted that the language of the [k]Hazars was different from the language of the (Oghuz Turkic) Seljuks of the Middle East, yet resembled the language of the (Oghuric Turkic) Bulgars far to the north. This is a very telling comment; as it attests that, by that time, the [k]Hazarian diaspora spoke a somewhat hybridized language—namely: one that incorporated elements of Oghuric and—once in Eastern Europe—indigenous Eastern European tongues. How so? The Bulgars ALSO came to use what was effectively a Turkic-Slavic hybrid. Bulgar is a case-study in the degree to which the Turkic provenance of a tongue can dissipate over time. Today, vestiges of Turkic in modern Bulgarian are so sparse that the language is now categorized as primarily SLAVIC. This makes sense, as medieval Bulgarians became Eastern Orthodox Christian, and their lingua-franca was therefore primarily dictated by the (prescribed) liturgical language: Old Church Slavonic (as attested by the Codex Zographensis from c. 1000). They abandoned their Turkic identity; and their Turkic linguistic roots along with it.

The fact that few traces of the Turkic provenance of the Bulgarian language—or, for that matter, the Hungarian language—remain reminds us that what happened with the [k]Hazarian diaspora was not unheard of. Indeed, there are some rough analogies between these two—nay, three—cases. With their new identity, the Bulgars were determined to purge their newfangled culture of their pagan origins in Old Great Bulgaria (i.e. Volga Bulgaria; read: western [k]Hazaria). Their revamped (Christian) identity took on a distinctly Danubian ethos; entirely disconnected from its Turkic roots—vestiges of which remain…in the form of Bashkir, Chuvash, and other Tatars in the original homeland. (Unfortunately, the Sabirs no longer exist.) The culmination of this process is recounted in the “Boril Synodic” [Book of Boril] from c. 1211-14. Similarly, Yiddish is now categorized as primarily GERMANIC. (For how a similar thing happened with the Magyars-cum-Hungarians, see Postscript 1.) It comes as no surprise, then, that Bulgarians today do not include the Onogur ruler, Kubrat Khan in their national origin story; but rather affiliate themselves with a folk-hero who had nothing whatsoever to do with their actual (Turkic) provenance: the Roman military leader, Theodore of Heraclea Pontica. We are thus furnished with another case-study of a Turkic people asserting a novel identity; which entailed eliding their Turkic origins. As a consequence, Bulgarian is no more seen as a Turkic language than is Yiddish. {120}

This is yet another reminder that ethno-centricity is not merely based on conceit; it is based on somewhat delusive thinking. For it invariably behooves participants to honor a confabulated historiography—as erroneous as it is self-serving. The Bulgars converted from Tengri-ism to Christianity c. 864—during the reign of King Boris-Michael. They thus slowly redefined themselves as an Eastern European people rather than as former Steppe peoples. Meanwhile, the [k]Hazarian diaspora would retain its creed (Judaism), yet eschew its Turkic identity in favor of an Occidental one—thereby adopting a more European ethos.

These parallels are instructive.

Another indication of the influence the language of the Tatars had on the development of Old Yiddish (effectively: a hybridization of Oghuric elements and Germanic elements, with a smattering of Slavic influences) comes from the 11th century. In his “Diwan Lughat al-Turk”, the Kara-Khanid lexicographer, Mahmud ibn Husayn of Kashgar (a.k.a. “Al-Kashgari”) discussed the recent expansion of Turkic language influences into Eastern Europe. In other words: This was a known phenomenon at the time.

A key point to consider: That the Sephardim in 11th-century Lotharingia (notably, Rashi) used a language that exhibited no Germanic influences (they used Zarfatic, which was from France) indicates that Sephardim in that area were NOT adopting Germanic lexemes during the relevant period. This means that Old Yiddish did not emerge amongst Sephardic Jews who happened to reside in the Rhineland; but amongst OTHERS who practiced Judaism and had recently started arriving in the area…and were thus more apt to adopt Germanic lexemes. (Rashi’s tongue, Zarfatic, was NOT a precursor to Old Yiddish.) Couple this insight with the fact that Rashi referred to the Ashkenazim as OTHERS, and the conclusion is quite clear: Ashkenazim did not come from Sephardim. They came from somewhere else. And the only “somewhere else” was from the east.

Had the Ashkenazim been former Sephardim, there would be traces of linguistic intermediaries—especially linguistic vestiges of Zarfatic. There weren’t. In fact, into the modern age, many in the Pale of Settlement continued to use Turkic terms like “kabak” (squash), “bülbe” (potato), “solet” (meat and potato stew), “knish” (meat-filled dough), “titun” / “tyu-tyun” (tobacco), “kaplak” (coarse cloth), “torba” (bag), “kh[a]lat” (jacket), “brislak” (vest), “brust-tukh” (bodice), “patsheyle” (female head wrap), and “kolpik” [from “kalpak”] (fur hat)…to mention a dozen. {102} “Yarmulke” is, of course, the most explicitly Turkic term still used—to the present day—by Ashkenazim. There is no likely scenario in which Sephardim who had migrated into Eastern Europe would have adopted such vernacular (thus jettisoning long-used Sephardic terminology for no apparent reason). This was all lexical residue from the Ashkenazi Jews’ Turkic past. {50}

Why not MORE? Well, happily, we have another case study available to us—where Steppe languages from the the Ural region migrated westward into eastern Europe. The Uralic tongue of the Magyars (modern Hungarian) is not exactly a treasure trove of Turkic lexemes either. {111} Why not? Mother tongues dissipate as dominant tongues take over. Such changes happen during geo-political—and cultural—transitions. Even so, we can usually find SOME vestiges if we look hard enough. {112}

In sum: When some contend that there is no clear linguistic genealogy from Common Turkic to the earliest incarnation of Yiddish, one need only retort that there is no path from Zarfatic to Old Yiddish either; and that, had the latter been the case, there would almost certainly be glaring vestigial features—either lexically or grammatically. There are none.

To understand the linguistic process by which [k]Hazarian would have morphed into Old Yiddish, it is necessary to take into account the process of “re-lexification” by which the latter was formed. In assaying the retained grammatical structure of Old Turkic, we find that the native vocabulary was gradually transplanted with Slavic and Germanic lexemes—as would be expected. Hence a nascent Turkic tongue (with traces of Sogdian, due to progenitors’ participation on the Silk Road) underwent a metamorphosis as it encountered linguistic influences from Slavic (mostly Sorbian) and Germanic (mostly Bavarian) peoples during its migration westward from the Pontic Steppes—through Bohemia / Moravia, then Silesia, then Bavaria—toward the Rhineland. As it happened, the [k]Hazars would have ALREADY been well-versed in Old Slavic—especially Sorbian (replete with Severian and Drevlian variants) as a result of to their trading patterns from the previous few centuries. {95}

The Silk Road is an important factor here. Not all Jews who were merchants across Eurasia were Radhanites. Some would have been [k]Hazars. In any case, the record shows that Beth Israel was not the monolithic group so often portrayed in Judaic historiography. Far from homogenous, world Jewry was a diverse tapestry of different peoples from different places—some of whom were Semitic, some of whom were not. The preponderance of evidence belies the over-simplified tale of all the world’s Jewish people being a singular diaspora emanating from Judea via pristinely Hebrew bloodlines. {93}

Bear in mind: Subsequent linguistic accretions that occurred in Yiddish during the Pale of Settlement are a moot point, as they would have been adopted long after the fact; so say nothing about Ashkenazi origins. (Those who take umbrage with the present thesis are often quick to point to Hebraic elements that eventually made their way into the Yiddish vernacular.) The question is: How did Yiddish ORIGINALLY exist? Surely, a lot happened in the intervening time—much of which would have masked the Turkic provenance of the earliest speakers. Predictably, Hebrew terms were steadily incorporated into the lexicon, as Ashkenazim slowly became acquainted with the Talmudic tradition—starting in the 16th century. Assaying what happened LATER is beside the point when we’re inquiring into where something BEGAN.

With regard to the Halakha, the process of syncretism amongst Ashkenazim went into overdrive in the advent of Joseph ben Ephraim Karo’s commentary on Yaakov ben Asher’s “Arba’ah Turim” (the “Beth Yosef”; summarized as the “Shulchan Aruch”) in the 1550’s. Even then, the adoption of the Talmudic tradition—theretofore an exclusively Sephardic phenomenon—by Ashkenazim was tempered by the commentary of a rabbi from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: Mojzesz ben Isserl ben Josef of Kazimierz (alternately rendered “Moshe Isserles”, meaning “Moses Israel”; a.k.a. “ReMa”), who operated out of Krakow. Naturally, there was some push-back from some Ashkenazim against the incorporation of the (foreign) Talmudic tradition into their own Mosaic creed. {94}

While Karo was himself Sephardic (he was from Toledo, in Andalusia), he was seen as speaking for all of Beth Israel; and eventually came to be known—even amongst Ashkenazim—as “Mar-an” (“Our Master”). This attests to the degree of memetic transference that ultimately occurred—from the Semitic part of Beth Israel to the Turkic part of Beth Israel. ReMa’s campaign to stave off Sephardic influence was to no avail. Ashkenazim eventually adopted the Talmudic paradigm, and embraced the Rabbinic legacy that had been sustained by the Sephardim since the era of the Zugot (through the Tanna-im, Amora-im, and Savora-im…to his contemporaneous Gaon-im). The Mishnaic and Masoretic canon, which had been entirely foreign to the [k]Hazars, soon became a part of their descendants’ repertoire.

As might be expected, some protest came from Ashkenazim who were reticent to adopt the Talmudic / Rabbinic traditions of the Sephardim. This was attested by the array of invective composed the Karaites at the time. Such reluctance was short-lived. By the time Elijah ben Zalman “ha-Gaon” of Vilna was redacting the “Sefer Yetzirah” [Book Of Creation] and Moses Mendelssohn was contributing to the Haskalah (also in the 18th century), Ashkenazi culture had fully incorporated the Talmudic tradition into its own.

To reiterate: Such memetic accretions occurred long after the fact; and therefore tell us very little about the origins of Ashkenazim. So those who argue AGAINST the [k]Hazarian origins of Ashkenazim by citing such developments (“Look at the Hebraic elements found in modern Yiddish!”) are engaged in misdirection. Any developments after c. 1500 are completely beside the point. Exigencies during the relevant period (the 11th thru 15th centuries) are not to be confused with later developments in Ashkenazi Judaism—like, for instance, that of [c]Habad Hassidism, which was inaugurated by Menachem Mendel of Haradok [Vitebsk] and Shneur Zalman ben Baruch of Liozna [Lyady] in the 18th century. {97}

So why don’t we have any Jewish liturgical material in Turkic from the Early Middle Ages? If the [k]Hazars were, indeed, predominantly Jewish, wouldn’t there be at least SOME record of it in a [k]Hazarian language? Well, not if it was all destroyed.

But wait. The fact that there are no surviving documents from a thriving, quasi-literate kingdom is rather odd, is it not? Yes and no. {101}

Here’s what would refute the present thesis: If we DID have oodles of [k]Hazarian documents, and (A) none of it indicated anything about their relation to the Jewish Faith and/or (B) at some point it mentioned OTHER Jews (i.e. those who were not fellow [k]Hazars) who were identifiable as (antecedents to) Ashkenazim. (A) would effectively mean: “Judaism, you say? Most of us are not that.” (B) would effectively mean: “Ashkenazim, you say? We’re not them.” Either would refute the thesis that Ashkenazim were a later incarnation of the [k]Hazars.

Documentation by the [k]Hazars themselves would, of course, be tremendously helpful. But what we now have from them is, well, virtually nothing. Clearly, all relevant material—insofar as it existed at one point—was lost and/or destroyed. Destroyed by whom? Probably by the Slavic conquerers who felled their empire…and, within a few generations, had converted to Christianity. Pursuant to said conversion, the Slavs / Varangians would have probably dispatched much of the non-Christian material that remained within their domain—[k]Hazarian and otherwise.

Meanwhile, the [k]Hazarian exiles themselves slowly migrated across Kieven Rus with whatever they could carry—or were allowed to carry—in their horse-drawn carts. Disaffected nomads tend not to transport libraries.

Bottom line: There was surely some [k]Hazarian literature that existed at one point. The fact that none of it remains tells us that—however much of it there may have been—it was entirely lost and/or destroyed; which accounts for the paucity of documentation with which we are now dealing. The lack of such documentation is not evidence of non-Jewishness; it merely attests to the fact that no documentation—of ANY kind—survived.

Extensive scholarship has been devoted to tracing the phylogeny of the potpourri of Turkic languages that eventually came to exist; yet only a minuscule amount of attention has been paid to the metamorphosis of the [k]Hazarian lingua franca (from the Oghuric line) to the Germanized “Yiddish” tongue that emerged during the High Middle Ages. Given the present thesis, though, it should come as no surprise that vestiges of the population’s Turkic roots are evident in the Yiddish vernacular.

Notable is the term for the Judaic headpiece: the “yarmulke”. The term is based on the Turkic “yargmuluk”, meaning “protective dome / canopy” (i.e. a cap); NOT, as some have contended, from the Talmudic phrase “fear of the king” (which, in any case, was from Syriac). Tellingly, this well-known neo- Turkic lexeme was used across Eastern Europe…instead of the Hebraic “kippah” (which, as it happens, ALSO means “protective dome / canopy”). This convention would have been rather odd had the Ashkenazim’s roots been Semitic; especially considering the term pertains to an overtly religious item (which normally warrants etymological continuity).

Well, then, what about female headdress? The head-wrap worn by Ashkenazi women is called a “tikhl” instead of a “mitpa[c]hat”. The latter is based on the Hebrew term for cloth, “tipa[c]h” (with the prefix “mi- ” meaning “from”, and “-at” appended at the end). Some attribute the Yiddish term to the German word for cloth, “tuch”, which derived from the Old / Middle High German “tuo[c]h” (the word that would have been in use during the relevant period). This is possible, though unlikely. (“Tikhl” probably does not have any relation to the Bavarian terms, “tu[s]che[r]l” or “tiachal”.)

It is more likely that “tikhl” shares its origins with that of the Turkic (spec. Chuvash) term for a woman’s head-wrap: “tukhya”. It might possibly even be a melding of the Turkic and Germanic lexemes. In any case, it remains a mystery why the Ashkenazim opted for “tikhl” in lieu of EITHER the Hebrew term for a cloth covering (“mitpa[c]hat”) OR the term used by Sephardim at the time (“pe’ar”). Clearly, there was a disjuncture in vernacular. {68}

Also notable is the Yiddish term for prayer, “davnen”, which is unique to Ashkenazi Jews; and is decidedly different from the traditional Hebrew term, “tefillah”. {61} Needless to say, propitiation is an integral part of a sacred creed: a holy act with a specific name. Why, then, would a term be used that was different from the one used in rabbinic (Mishnaic / Masoretic) lore? Had the Ashkenazim come from a Sephardic background, this would have entailed jettisoning a Hebraic moniker in order to adopt a term with an alternate etymological background–a highly unlikely scenario. Meanwhile, there were two words for soul / spirit in Old Turkic (which seem to have come from Sogdian or Middle Persian): “khut” and “dukh”; while “-nen” / “-nan” was the Turkic suffix for “in” / “of”. In Old Yiddish, the term for a priestly blessing was “dukh-nen” [in/of the soul]. {61} The same goes for “shul” (from the German “schule”) instead of the Hebraic “yeshiva” or “bet[h] midrash”. Under no circumstances would Sephardim have jettisoned the Hebrew term for “place of scriptural study” in favor of a Gentile term.

There are numerous examples. Ashkenazim opted for “zelik” (from the German “selig”) instead of “kodesh” for “holy”; which became a popular given name in Ashkenazi communities. They also opted for Sieg[e]l instead of “Khatam” (meaning “signet ring”; the original talisman known for exhibiting the seal of Solomon). For “pious”, Ashkenazim use the term “frum” instead of the Talmudic “khumra”. Tellingly, the 12th-century Tosafist (and maternal grandson of Rashi), Jacob ben Meir ben Samuel of Troyes never used the term, “frum”. This likely means that it had NON-Sephardic origins. And for “redeem”, Ashkenazim adopted “oysleyzn” from the Germanic “erlösen” [redeemed] / “erlöser” [redeemer] instead of the Hebraic “geul” / “go- el” (or even the Aramaic “yeshuah”). This would be rather odd had the Ashkenazim been from a Sephardic background. Other notable lexical transplants include the Germanic “stern” instead of the Hebraic “kokab” [alt. “kochav”] for star.

When moving into a new region, for a (Talmudic) Jewish community of Semitic heritage to suddenly eschew Hebraic (Mishnaic / Masoretic) terminology in favor of a patently non-Jewish vernacular would have made no sense.

Then there are everyday items. The Yiddish word for potato (“bulbe”) comes from the Turkic “bülbe”. The Yiddish word for noodles (“lokshe”) comes from the Turkic “laksha”. The Yiddish word for a sac (“torbe”) comes from the Turkic. The Yiddish word for a long garment for men (“kaftan”) comes from the Turkic. The Yiddish word for “happiness” (“glik”) is likely derived from the Old Turkic “got-lik”. Etc.

How in heaven’s name would Turkic lexemes have been incorporated into Ashkenazi vernacular if they’d split off from Sephardim? Even something as simple as the Yiddish salutation, “welcome” seems to have Turkic undertones: “borekh-habo” (a locution that–ostensibly–has something to do with blessings).

Moreover, if the first Ashkenazim had a tradition that was couched in Hebrew (as did the Sephardim), they would not have opted to transition to Germanic onomastics in lieu of Semitic nomenclature. Note, for instance, the use of the Germanic name “Loew” / “Löwe” rather than the Hebraic “Ari” / “Arya[h]” / “Aryeh” (alt. “lah-yish”) for “lion”. {75} This is peculiar, as the iconic animal is often associated with Judah (“Yehuda”)…and even with god himself (“Ari-El”). No Semitic Jew would have been inclined to adopt this Germanic lexeme IN LIEU OF the Hebraic lexeme. Meanwhile, “A[r]slan” is Old Turkic for “lion”, and remains a common Ashkenazic given name. When Sephardim would alter Biblical (i.e. Hebraic) names, they typically just modified their morphology—as with, say, “Elias” for “El-i-jah”.

Other Turkic given names occur sporadically amongst Ashkenazim—as with “Irek” [liberty] and “Ai-gul” [moon-flower]. {27} Other Turkic lexemes that crop up in Ashkenazi onomastics include “silu” [beautiful] and “güney” [south]. Also notable is the use of the Old Turkic “Kaplan” [alt. “Kaplun”] in lieu of the Hebraic “tigris” for “tiger”. Then there’s “Mendel”, the diminutive of the German for “man”, in lieu of the Hebraic name, “Mana[c]hem”. “Sorkin” seems to have something to do with “Sarah”. Why the Germanic when the Hebraic was available?

Some other (normally Hebraic) given names ended up having a Slavic bent–as with “Rivka” instead of Rebecca, or “Rashka” instead of Rachel. Again: This is a peculiar onomastic choice considering these were Biblical names. Meanwhile, “Bog-dan” is Slavic for “god-given” (alt. gift from god). Why would a Jewish family, in adopting a surname, abandon a coveted religious term (the Hebrew “min[c]hah”) in favor of a foreign onomastic…unless, that is, they didn’t have such a term in their repertoire in the first place?

There are myriad other indications of the NON-Talmudic provenance of Ashkenazim. “Alt-S[c]hul[er]” was coined as the term for the original (“old”) synagogue in Prague (instead of, say, “Beth Midrash” or “Beth Knesset”). Using the German word for “school” for a synagogue is probably not something Sephardim would have been inclined to do. Another telling clue is “Roth” instead of the Hebrew “Edom” for “red”. Nobody with a Semitic background would have been inclined to use “Rothstein” in lieu of the medieval Hebraic “Adamah”. “Roth[en]schield” is another interesting case (see Postscript 1).

An adumbration of Old Turkic vernacular can be found in the “Diwan Lughat-i Turk” from the late 11th century. Composed by a Kara-Khanid scholar from Kashgar, the work documents the migration of Turkic peoples and Turkic LANGUAGES into eastern Europe in the preceding century or so. (Good luck getting your hands on a copy. I suspect it is a treasure trove of lexical gems.) For the present inquiry, a point of departure would be to identify cognates between Old Turkic and Old Yiddish—specifically those that have roughly the same meaning. (My own observations, here, are surely only the tip of the iceberg.)

We might then consider a work in Old Turkic vis a vis Old Yiddish. For the former, we might look to the “Irk Bitig” (Book of Divination) from the 9th century (which would need to be transliterated from Old Turkic runes). The best sources of early Yiddish would be either the “Dukus Horant”, a Judaic adaptation (from the 14th century) of the Germanic legend of Kudrun (from the previous century), or the “Shmuel-Bukh” (Samuel Book) from the 15th century. {83} In juxtaposing these works, we would find that it was during the intervening five to six centuries that the preponderance of linguistic metamorphosis would have taken place—whereby the [k]Hazarian diaspora abandoned their native (Turkic) tongue and adopted a palpably Germanic one. It makes sense, then, that the groundbreaking Ashkenazi tract, the “Vitry Ma[c]h[a]zor” was not composed until c. 1100 (about a quarter-millennium after the “Irk Bitig”). That is to say: It was only composed once a distinct ethnic identity had been asserted in the new land: Ashkenaz.

Another indication that there was an independent Jewish community amongst the Turkic peoples is the emergence of the Old Bulgarian Book of Enoch. This text (a.k.a. the “Book of the Secrets of Enoch”; alt. Second Enoch) was unrelated to the original Book of Enoch, and was clearly not in the Mishnaic / Masoretic tradition. (Thus: Judaic scripture originally composed in a Slavic rather than Semitic tongue.) Remarkably, the first manuscripts of this book emerged amongst the Bulgars–a Turkic people who, it should be noted, originally hailed from the Pontic Steppes. While clearly drawing on antecedent Judaic lore (as with, say, the exaltation of Melchi-zedek), the text does some strikingly anomalous things–notably: designating the central place of worship for the ancient Israelites as “Ahuzan”. (!)

In light of all this, it is also important to look for countervailing evidence to the present thesis. Here, this would entail identifying cognates between, say, Zarfatic (including its Occitanian variant, Shuadit; used by none other than Rashi) and Old Yiddish. Doing so would help ascertain whether or not the Ashkenazim might have a Sephardic background. (Surely, traces of Zarfatic would crop up in the Yiddish vernacular if Ashkenazim had Sephardic provenance.) So far as I’ve found, though, no such cognates exist—an absence that would be inexplicable had the Ashkenazim hailed from western Europe. There are no vestiges of Tosafot in the “Dukus Horant”—a peculiar absence had its authors come from a Sephardic tradition. The work was clearly not composed by those who had a Zarfatic linguistic background. {70}

Another indication of the Turkic origins of medieval Yiddish is its grammar. Intriguingly, its periphrastic conjugation is neither Germanic nor Semitic in nature. (MODERN Hebrew incorporates periphrastic conjugation, UNLIKE Classical / Mishnaic Hebrew. As it turns out, it adopted this grammatical feature from Yiddish; so using this particular feature of the new lingua-franca as evidence of its speakers’ Semitic origins would be question-begging.)

Ashkenazim also opted for the Germanic “Weiss” instead of the Hebraic “Laban” for “white”. This is odd, as “Laban” is a Biblical name that was familiar to all Jews. (It was Isaac’s brother-in-law.) Also note “Taub[er]” / “Daub[er]” (from the Middle High German “tube”) instead of the Hebrew “Yonah” for one associated with a dove. This is peculiar, as “Jonah” is a Biblical name.

We also encounter generic terms like “Liub-wine” (later rendered “Lewin” / “Levin”), meaning “dear friend”, which is often—erroneously—conflated with names based on “Levi”. (The Anglicized version of that lexeme was “Leof-wine”.) If we were to suppose that “Levin” pertained to the Levites, we would be forced to posit an onomastic incongruity. For instead of “ben Levi” (which would be consistent viz. Hebraic nomenclature), we encounter “Levinowitz”, “Levinson”, and “Levinski” (where the “v” is sometimes “w”). Those surnames use Germanic / Nordic / Slavic patronymics for the (Hebrew) Biblical name of a hallowed tribe—entailing an odd etymological disjuncture.

Granted, some aspects of (the predominantly Germanic) Yiddish may be attributed to Slavic influences. However the language retains both definite and indefinite articles, which must be from linguistic sources other than Slavic. This may well be indicative of Turkic origins. (The Germanic elements of Yiddish are evident in its verb-second syntax, as well as significant parts of its lexicon.) Worth noting is the use of the suffix “-te” in Yiddish for the female version of something; which is from Babylonian Aramaic, not from (the Middle Aramaic-inspired) Masoretic Hebrew that is palpable in Sephardic vernaculars. Interestingly, the Yiddish term for grandfather, “[d]zeyde” has Slavic roots. This is a peculiar choice, as it is used in lieu of “saba”, the root of which is the Hebrew word for father: ab[a]. Both “ab[a]” and “am[a]” are basic words in the (Semitic) Jewish lexicon—words that one would presume would not be transplanted by Gentile terminology—especially when it comes to anyone with Semitic provenance.

Further work needs to be done on the vernacular of Old Yiddish by (impartial) linguistic scholars. A complete survey of the Yiddish vernacular goes beyond the scope of this essay. But the available evidence is in keeping with the present thesis.

It is worth taking pause, and posing the question: If the Ashkenazim’s ancestral tongue was Turkic, then why aren’t there MORE traces of it in Yiddish than there are? For even after the adoption of a highly Germanized tongue, one would still expect to find vestiges of the abandoned Turkic vernacular. Yes and no. Keep in mind: The ALTERNATIVE to the present explanation is that the forerunner was a (Sephardic) Zarfatic tongue, for which we find ZERO traces. That disappearance would be even more implausible, as there was a long-lived Talmudic tradition by that time…which would need to have been entirely discarded by the break-away sect. Ockham’s Razor provides us with the most likely explanation: the Ashkenazim had a provenance that was not Sephardic.

As mentioned, for indications of how Yiddish emerged from Turkic roots, the best place to look is the 14th-century proto-Yiddish epic, “Dukus Horant”. As would be expected, the work that exhibits palpably Turkic linguistic features. It is based on an old Germanic legend about a dastardly Norman prince, Hedinn (alt. “Hartmut”) and his dealings with a fictional Germanic king: Hogni (alt. “Hagen[a]”). More specifically, it was about Hedinn winning the hand of Hogni’s beautiful daughter, Hild[r] / Hilde (alt. “Kudrun” / “Gudrun”). In the Ashkenazic rendering, Hartmut (as “Horant”) is made the hero instead of the villain. He must prove himself to Hilde’s father (cast as a Byzantine king: “Hagen”) by going through various trials. The fact that Ashkenazim resorted to antecedent Germanic lore to write their first epic is quite telling. It shows that they eschewed the folklore that they’d previously had at their disposal, and were seeking an alternative. In no other instance can there be found material created by a Jewish community that was disconnected from the Mishnaic / Masoretic (read: Talmudic) tradition; and was composed in a language with no Hebraic precursors. It’s not like the Talmudic tradition was bereft of parables; or lacking in endogenous folkloric material. It already had a surfeit of both. (Note, for example, the fables compiled by Berechiah ben Natronai Krespia “ha-Nakdan” in the late 12th century: the “Mishle Shu’alim”.) The [k]Hazarian diaspora, on the other hand, WOULD have been looking to appropriate whatever useful Gentile material they encountered; as they had a limited Judaic heritage from which to work.

What of the native [k]Hazarian language? Might there be any clues there? Alas, we don’t know much about their particular dialect of (Oghuric) Turkic. The [k]Hazars referred to Saturday (the Sabbath) as “shabat kun”–a clear mark of their Jewish culture. We know that this was not the result of a Semitic background; for the Kuman peoples–who spoke Kipchak and were not Jewish–ALSO came to use the term for that (auspicious) day of the week; being, as they were, vassals of the [k]Hazar Empire (ref. Kevin Alan Brook’s “The Jews Of Kazaria”). The terms used by the [k]Hazars for all the other days of the week–which had no religious significance–did NOT have Hebraic etymologies. This means that the [k]Hazars treated this particular day in a unique manner, labeling it according to Judaic convention…even as they retained the Turkic vernacular for all things secular (e.g. the other six days of the week). In other words: The use of this term for the Sabbath day was due to semiotic pertinence rather than linguistic inheritance. {115}

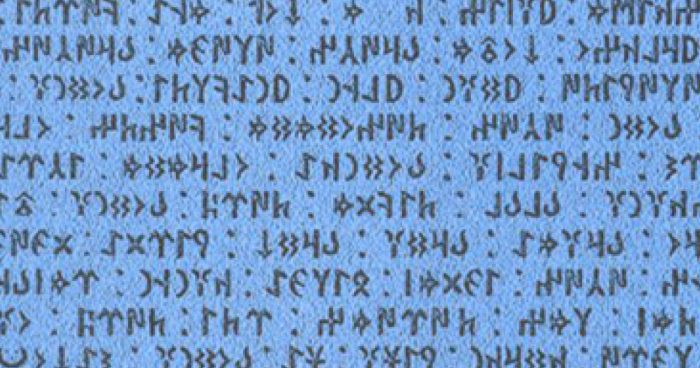

Meanwhile, by the 10th century, the [k]Hazars seem to have adopted a variant of the Samaritan alphabet for their writing. This indicates that there were Semitic ORTHOGRAPHIC influences in [k]Hazarian lore; and it was not Hebraic. More to the point, [k]Hazarian lore was derived from sources that did not use either Mishnaic or Masoretic Hebrew (i.e. sources used by Sephardim). In sum: Their lore was–in part–Abrahamic lore, yet it was not conveyed via Hebraic means (as was always the case with Sephardim–from Maghrebis to Andalusians to Tosefot). Their Judaic material come to them via alternate intermediaries. Such sources likely came to the Pontic Steppes via Persia at some point in Late Antiquity. It is possible that such memetic transmission occurred via the peoples known as the “Mishars” (alt. “Nizhgars”), as well as the Burtas and the (Jewish) Radhanites: Persian and Eurasian peoples–many of whom traveled the Silk Road and used Sogdian; some of whom were reported to have converted to Judaism.

Note, though, that it was not until the last days of the empire that some [k]Hazarian documents were written using this quasi-Samaritan script. The empire even came to use that script on some of its coinage. {25} Pursuant to the first Muslim conquests of the 7th century, many Samaritans were displaced to Persia, which is precisely the route by which Judaism would have come to the [k]Hazars. (Keep in mind, the Samaritans recognize only the Torah…which explains why, to this day, Orthodox Jews refuse to consider Samaritans properly “Halakhic”.) And so it went: The so-called “kadmonim”, founders of the Ashkenazi Halakhic tradition, trace back to–you guessed it–about a thousand years ago. That the [k]Hazars used the Samaritan alphabet makes sense, as it was not uncommon for Samaritan script to be used to compose works stemming from Babylonian Aramaic–as demonstrated by the “Tulida”.

[k]Hazarian coinage from the 9th century praised Moses as the “messenger of god”…in Samaritan script. In his “Kitab al-Fihrist”, the 10th-century Arab historian, Abu al-Faraj Muhammad ibn Ishaq al-Nadim even commented that the [k]Hazars wrote using a Hebrew-like script. {25} Unsurprisingly, other [k]Hazarian coinage was written in variants of Turkic script (i.e. Old Turkic runes, which were used for Kipchak in its earliest phase). Archeology has even uncovered syncretic iconography, combining the Judaic menorah with various ancient Turkic symbols. (!)

That’s not all. The necropolis at Chelarevo in the Balkans had a cache of Turkic artifacts from the 8th and 9th centuries–likely from the Bulgarian Khanate (which was primarily Tengri-ist until c. 864 when their leader, Boris converted to Christianity). Many of those ALSO made use of the menorah. (!)

The Bulgar Khanate bordered the [k]Hazar Empire along the Dnieper river; and the two peoples shared iconography–as attested by the Treasure of Nagy-Szent-Miklos. The use of menorahs on such artifacts would be inexplicable but for the current thesis.

Another key point: The origins of the Ashkenazi Hebraic dialect–which was eventually established for liturgical purposes–seems to be largely disconnected from the Mishnaic / Masoretic Hebrew of the Talmudic (spec. Amoraic) tradition. The discrepant origins of these two medieval renderings of Hebrew is very telling. Note that the medieval incarnation of Hebrew (spec. Masoretic) is primarily traced to Andalusia…and, even further back, to the Mishnaic Hebrew of the “[c]Hazal” and “Geonim” (which would have been based on Babylonian Aramaic). The Ashkenazi dialect of (pseudo-)Hebrew was a post hoc creation that was completely unrelated to the discursive practices found in the Talmud.

As would be expected from the timeline of events, Yiddish did not emerge as a distinct language until the late 13th century. The oldest surviving text that incorporated this new hybrid language was a liturgical document (“ma[c]h[a]zor”) from Worms written c. 1272. The text primarily used a Germanic lexicon and grammar…along with various Slavic, Turkic, and even Syriac terms. (There were no distinctly Hebraic elements.) Tellingly, this document is rarely made available to the public. This is to be juxtaposed with the aforementioned “Vitry Ma[c]h[a]zor”: a ruling on liturgy from c. 1100; so called because it was composed in Vitry (northeastern France) by a student of Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes (a.k.a. “Rashi”): Simhah ben Samuel. THAT tract was composed in the Zarfatic idiom; and was done to rebut the liturgical positions of those pesky foreign Jews to the East: the Ashkenazim. (It has also palpable influences from the “Seder Amram Gaon” and the “Halakhot Gedolot”.)

It was not until the late 14th century that Yiddish came to be a full-fledged language, as attested by the earliest instance of an distinctly Yiddish document: the “Cambridge Codex” from c. 1382 (discovered in the archives of the Ganiza at Fustat in Egypt). The codex was comprised of four texts: “Gan Eden”, “Avraham Avinu” [Abraham Our Father], “Moshe Rabbeinu” [Moses Our Teacher], and “Yosef Hatzadik” [Joseph the Righteous]. As we might expect, the material is slightly discordant with standard Biblical narratives. In the codex, there is a segment from the German epic, “Kudrun”…which was not composed until the mid-13th century. (That epic was likely inspired by the Norse “Hjadningavig”; a.k.a. the “Saga of Hild”.) Would Sephardim have been inclined to incorporate Varangian lore into their literary repertoire?

Also in the Cambridge codex is a segment from the aforementioned “Dukus Horant”, which was composed in the 14th century; and was also inspired by “Kudrun”. This indicates that the earliest Ashkenazim were dealing with fairly recent material (that is: recent at the time). In its initial iteration, Yiddish literature seems to have been more influenced by Germanic material than by Hebraic material–exactly as we would expect given the origins of the Ashkenazi Jews. What we see here is a disconnection from their Turkic roots, leaving a folkloric vacuum to be filled by what was at hand IN THAT REGION.

Another thing worth noting: Literature that was exemplary of the hallowed Sephardic legacy in France–like the “Pirkei Avot” and the “Ma[c]hz[o]r Vitry”–did not circulate amongst the Ashkenazim during this period: a peculiar liturgical omission had the Ashkenazim been the progeny of that community. We should recall that when they first arrived in Lotharingia, the [k]Hazarian diaspora would not have conjured Yiddish from whole-cloth. Insofar as they abandoned their ancestors’ Turkic tongue, they would have begun using the lingua franca of their new home: medieval German. Sure enough, “Adir Hu” is a medieval German hymn sung by Ashkenazim for Seder. Why would this exist given that there later came to be a Yiddish version of “E[c]had mi Yodea”? The only explanation is that, for these newly-arrived Jews, the origin of the hymn was not Semitic.

It is also very telling that the first time the topic of the origin of Ashkenazim (and Yiddish as a distinct language) was broached was not until the 16th century (by the Frankonian philologist, Elia Baxur)! This means that the issue was not a major focal point until modern times. It only started to become a point of contention when the “aliyah” (in-gathering of the diaspora in the Holy Land) started to become modish in certain precincts–prompting the need to contend with why Yiddish was, well, Yiddish. (The eventual solution was to eschew it in favor of a modern version of Hebrew.)

As philology is not my vocation, the examples provided presently should suffice to make the point at hand: Over the course of the 12th and 13th centuries, Yiddish was developed as a new-fangled language for a new-fangled people, who asserted a novel identity after the westward [k]Hazarian migration into “Ashkenaz”…which was itself an appellation retained from the [k]Hazars’ use of the Assyrian moniker for people of the Eurasian Steppes: “Ashkuza”. If even a dilettante like me can notice such things; surely there is much more for (impartial) scholars to offer.

When it comes to connecting the relevant dots, I leave it to (disinterested) philologists (spec. those who are well-versed in Turkic languages and in Yiddish) to do the rest. As with any other serious inquiry, those with conflicts of interest (that is: vested interests in certain conclusions) should be disqualified from such a project.

One thing that might be useful is a timeline of Hebrew terms being incorporated into Yiddish vernacular. It does not seem as though this has yet be done; and it would reveal much about what was and was not present during the tongue’s inception. There are, of course, some contemporary Yiddish words that have Hebrew etymologies—as with “[c]hutzpah”, “sim[c]ha”, “meshug[gen]a[h]”, and “mishpocha[h]”. However, such Hebraic terms were not incorporated into the Ashkenazi vernacular until the modern era (that is: long after the fact); so they are not indicative of the language’s origin.

One of the more popular objections to the present thesis pertains to onomastics. The contention is simple: There are very few PROPER nouns with Turkic roots used in Yiddish (that is: Turkic NAMES used by Ashkenazim). This is entirely beside the point. There is far more to linguistics than onomastics.

It makes perfect sense that Jewish communities did not retain Turkic surnames; as–naturally–there was an inclination to assert their identity as Jews (in contradistinction with other Turkic peoples). After all, as time went by, the [k]Hazarian diaspora sometimes opted to write using a Samaritan script (then, later, a pseudo-Hebraic script), not the prevailing Turkic script. Surely, they would have adopted names that were consummate with their (re-vamped) identity. Even so, family names like Burak, Khanum / Khatum, Kazan, Krak[h]mal, Kagan[ek], and Perchek exist to the present day amongst Ashkenazim. Kulaga is from the Bashkir “külägä”, a variation on the Old Turkic “kölge”. Lipka is literally the name of a Tatar ethnic group.

The vast majority of Jews in the region ended up adopting Germanic surnames for non-religious vocations. This was an onomastic convention that had no precedent in the Semitic (i.e. Judaic) tradition. While most Ashkenazim ended up adopting occupational surnames (typically ending with “-man[n]”; or even the patronymic “-[s]so[h]n”), almost no Sephardim opted to do so. This discrepancy is hard not to notice. {45}

When adopting a surname, some Ashkenazim even retained the Turkic term for a vocation–as with “Bak[k]al” (food vendor) and “Pamuk” (weaver). “Kilimnik” (carpet tradesman) combines the Old Turkic word for carpet (“kilim”) with the Slavic suffix used to designate an affiliation (“-nik”; as in “Kramnik”). (Here, the Germanic suffix would be “-man[n]”; while the Hebraic suffix would be “-um”.) {66} The Turkic term was used in lieu of the Hebrew terms: “shatiac[h]” and “marvad”. This alternate onomastic would not have occurred were the people to have had Sephardic ancestry. (It would not have made sense for them to have eschewed the Hebraic term in favor of the Turkic term.) Again, we find an exigency that would be inexplicable but for the present thesis.

Already mentioned is the Turkic origin of “Schwartz”. Surnames like “Jeljasze-wicz”, “Sulkie-wicz” / “Sulko-wicz”, “Achmato-wicz”, and “Abakano-wicz” have Lipka Tatar roots. “Khan” (often rendered “Kahan” or “Kahn”) is self-explanatory. And, of course, there is the surname “Kagan”. It is no secret that “k[h]agan” means “ruler” in Old Turkic. {33}

These are merely the most obvious examples of vestigial Turkic onomastics. Surely other Turkic surnames went the to wayside over time as the “Ashkenazi” identity came to the fore. Keep in mind, we are talking about a linguistic metamorphosis over the course of a thousand years. Countless Turkic surnames invariably disappeared into the local vernacular over the centuries. For example, in Greater Lithuania, there are Jews with the surname “Shahn”…which is inexplicable lest we suppose the moniker was either a variant of the Persian “Shah” or had a “g” in it at some point (meaning it was derived from the Turkic “Shagan”). The genealogy of names is a funny business; and etymology is nothing if not quirky. {49}

But wait. There are still other residual traces. “Bak[h]shi” is derived from the (Krymchak) Turkic word for (alternately) “garden” / “gift”. There are Ashkenazi names like Sevim and Khanum / Khatum–all with Turkic backgrounds. Other etymologies are unclear. While “karman” was Hebrew for orchard / garden, it was also Turkic / Slavic for basket / pocket. And “korchma” was used in both Old Slavic and Old Turkic for tavern / inn.

The Mas[h]hadi surname “Kaganovi[t]ch” was used by descendants of Jewish merchants of the Silk Road (likely Radhanties), who would surely have interacted with peoples of the Eurasian Steppes. The given name “Kozar” derived from a melding of Slavic and Turkic. The popular given name, “Lazar” (the Slavic / Turkic version of “Eleazar”) has Magyar and Bulgar roots. {34} (We discussed the Italic surname, “Kalonymus”, earlier. For more on that surname, see the Appendix.)

And it is likely that “Sagan” came from “Shagan”, a Turkic surname that is still used by Azeris and Kazakhs. It is possible that the name is related to the Aramaic term for Babylonian priests, “segan”–an honorific that had propagated along the Sogdian trade-routes. That is to say: The term exists as a result of the predominant language of the Silk Road during Late Antiquity. (It is almost certainly NOT derived from the Polish word for “kettle”.) Considering the location of the [k]Hazar Empire, it makes perfect sense that this popular Ashkenazi surname has Sogdian origins. (Note that the area just east of Rothenburg, in Silesia, came to be called “Sagan”.) This was no anomaly. Other neo-Aramaic words were incorporated into the [k]Hazarian vernacular via Sogdian–primarily religiously-significant terms like Messiah (in its Syriac form), hell (“tamu[k]”), and paradise (“us[t]mak”).

When it comes to juxtaposing (Semitic) Sephardim against (non-Semitic) Ashkenazim, another contradistinction is worth noting. Rarely did European Sephardim (i.e. the Jews of Andalusia and France) come to have family names based on the places in which they settled; as they tended to retain their Judaic surnames. There were a handful of cases where Sephardic families ended up with toponymic surnames. The difference is that they were ALREADY surnames (as with, say, “Toledano”, “Salvador”, or “Touro”), and were simply adopted–primarily from Arabic, Berber, Spanish, Portuguese, (Occitania) French, or Italian. None were sui generis. The use of such exogenous family names amongst Sephardim, then, was part of the natural course of events.

By contrast, Ashkenazim DID end up establishing novel family names based on places they settled during the Middle Ages–names that were concocted BY THEM for precisely that purpose. A moment’s thought reveals an indubitable fact: Only a change in ethnic identity would have prompted such a widespread change in surnames (to names that were sui generis); and–more to the point–a change in this particular manner (to wit: identifying with a new PLACE, but not necessarily with a new RELIGION). So…while it did happen from time to time, entirely newfangled onomastics based on PLACE was not nearly as common amongst Sephardim as it was with those Ashkenazim.

How does this comport with the present thesis? People who ALREADY resided in the region–or in Europe in general–would not have been moved to convert to Judaism; as there was no Jewish evangelism (and there was certainly plenty of dis-incentive to leave Christianity). The only explanation, then, is that the first Ashkenazim were people who were already Jewish, yet came from somewhere without a Semitic onomastic. Consequently, they arrived with surnames that they were inclined to jettison…and replace with names that were NOT associated with Christianity yet WERE associated with their new homeland. Heck, they called themselves people of “Ashkenaz”, an endonym that would not make any sense if they thought of themselves in Semitic terms. As we’ve seen, this applies even if they had the Biblical figure in mind. {42}

And so it went: Many of those in the [k]Hazarian diaspora opted for toponyms when they settled in Europe. When toponymic, the new surname was sometimes in reference to an entire region–as with:

- “Frankel” for Frankonia

- “O[e]streicher” for Austria

- “Bayer” for Bavaria

- “Schlesinger” for Silesia

- “Litwak” for Lithuania

- “Gurdji” for Georgia

- “Valadji” for Wallachia

- “Pollack” for Poland

- “Unger” for Hungary

…and, of course, “Deutsch” for those living in Germany. A surname could refer to general places—as with “Friedlander”. It could even simply mean “villager”–as with “Dorfman” or “Berger”. “Flecker” means a clearing in the woods. “Nordhaus” simply means a house in the north.

Most often, though, the toponym was based on a specific place. Here are FIFTY examples:

In the Rhineland / Lotharingia: Dreyfus for Treves / Trier[s], Oppenheimer for Oppenheim, Mintz for Mainz, Spiro / Shapiro / Sapir / Speier for Speyer, Epstein for Eppstein, Ettlinger for Ettlingen, Bacharach for Bacharach am Rhein, Florsheim, Landau, Hammerstein, and Heilprin / Heilbron[n]er / Halper[in] for Heilbronn.

In Saxony / Frankonia: Heller for Halle, Garti for Gartach (Württemberg), Eisenberg, Lipsky for Leipzig, Kissinger for Kissingen, Berlin, and Friedland[er] for Göttingen.

In Bavaria / Austria: Ruttenberg for Rothenburg, Auerbach [literally “meadow-brook”], Sulzberg, Linzer (Linz), Roth for Roth bei Nürnberg, Ginsberg for Günzburg, and Wiener for Vienna.

In Prussia / Pomerania / Silesia / Bohemia / Moravia: Wolin, Horowitz for Horovice, Gutfeld for Gutenfeld, Altschul[er] and Prager for Prague, Brandeis for Brandys, and Brin for Brno / Brünn.

In Poland: Danziger for Gdansk, Warshauer and Breslau for Warsaw, Krakauer for Krakow, and Posner for Posen.

In Greater Lithuania: Vilner for Vilnius, Twersky for Tverai, Persky for Pershai, Pinsky for Pinsk, Minsky for Minsk, Smolyansky [alt. “Smelyanski”] for Smolensk, and Gordon for Grodno.

In Volhynia / Galicia: Tartakover / Tartakower for Tartakov, Brody, Borsuk, Gulko, and Zaderikhvost.

And in Hungary: Budun for Buda[pest]. Some who descended from Magyars simply ended up with the surname “Madjar”.

Jewish families that settled in these places would have had alternate surnames prior to that time (as their progenitors lived elsewhere before they lived there). This means that they opted to change those surnames after arrival. What is telling is that almost no Sephardim opted to do this when THEY settled in Europe. Why not? Well, they ALREADY HAD (Jewish) surnames. Granted, a few Sephardim eventually adopted local surnames, some of which may have been toponymic (as with, say, Toledano); but that was certainly not the norm. {86}

Bottom line: Such disparate onomastic practices between Sephardim and Ashkenazim attests to two different heritages.

Also worth noting are names ending in “-thal” (German for “valley”), “-feld” (German for “field”), and “-berg” (German for “hill”): common toponyms. Other suffixes include “-baum” (tree), “-blum” (flower), “-blatt” (leaf), “-stein” (rock), “-bach” (stream), “-hoff” (farm), and “-heim” (home). (The suffix “-heim” led to names like bettel-heim [beggar’s home].) “Gaster” meant “guest” (from the German; though with an “-er” oddly appended at the end). It’s difficult to imagine a Sephardic family in Andalusia adopting the surname “Invitado” (or in France adopting the surname “Invité”). In the Rhineland, the [k]Hazarian diaspora probably did, indeed, initially feel as though they were guests—that is: visitors in a new land.

Sometimes, kinds of topography were combined—as with, say, Wiesen-thal (meadow-valley). Also worth noting are surnames ending in “-berg”–as with Korn-berg (grain hill), Grün-berg (green hill), Steinberg (stone hill), Eisenberg (iron hill), Weisselberg (white hill), Goldberg (gold hill), Kronenberg (crown hill), and Weinberg (wine hill; i.e. vineyard). This occurred with many geographical descriptions–as with, say, Grunwald (green forest). A potpourri of other surnames was adopted–clearly from a people who were seeking new monikers to assimilate. “Rosenthal” means “rose valley”. {51} Meanwhile, there’s Rosenberg (named after a town in the Rhineland) [rose hill], Bloomberg [flower hill], Rosenstein [rose stone], Rosenfeld [rose field], Rosenblatt [rose pedal], Rosenbaum [rose tree], and Rosenblum [rose flower]. (Of course, no Ashkenazim adopted “Rosenkranz” [rosary]; though “Blumenkrantz” was adopted.)

In no other scenario did Jewish people (elsewhere in the world) do this; as there was no reason to do this. (This does not discount instances in which some Jews adopted local names for themselves: a ubiquitous phenomenon. Hence we should not be surprised that some Andalusian Jews are named Esperanza, Merkada, Nina, or Zafiro.)

In many cases, Ashkenazim opted to make use of Germanic terms in lieu of Hebraic terms when transitioning to their new lexicon. Take, for instance, “finkelstein” [spark stone]. This was the term adopted for pyrite…instead of the Hebrew “bareketh”. For a Semitic people, such a choice would have been rather odd, as it names one of the twelve tribal stones of the breastplate of a high priest (ref. Exodus 28:17). Any community coming from a Hebrew-based background would not have been inclined to transplant a Biblical term (which they would have already been using) for a Gentile term.

We’ve already mentioned the use of the non-Semitic “schultheize” (later rendered “Schultz”) for a surname (a local term having to do with mercantile dealings). Ashkenazim also opted for the Germanic “Fechter” instead of the Hebraic “Lochem” for fighter. Meanwhile, they opted for the Germanic “Volf” in lieu of the Hebraic “Ze’ev” for wolf; and for the Germanic “Bär” / “Bër” in lieu of the Hebraic “Dov” for bear. (“Tov” means “good” in Hebrew.) The same goes for the aforementioned Yiddish term, “shul” (place of scriptural study): also taken from German. (“Yeshuv” was evidently not in the vernacular of the early Ashkenazim.)

Recall the peculiar treatment of Solomon’s fabled signet ring, on which his seal was engraved. Why would have practitioners of Judaism opted for “S[i]egel”, the Germanic term for “seal”, when “hotem” was already an auspicious Hebraic term amongst Sephardim? Ashkenazim adopted the surname because it was affiliated with a trade: those who made the signet for wax seals. There was clearly a population of Jews in Ashkenaz about a millennium ago who were shopping for new surnames; and who did not already have a Hebraic vernacular from which to work.

Clearly, the Jewish community that came to known as “Ashkenazim” did not have a Semitic background. If they DID, the incumbent liturgical terminology would have been retained even as their lingua franca changed.

The “Kozare” district in Kiev does not shy away from advertising its Turkic–specifically, [k]Hazar–origins. And, as mentioned earlier, the medieval name for central Ukraine and Crimea was “Casari”–a label that was used on maps until the 18th century. (!) These were clearly vestiges of an earlier Turkic nomenclature. {49} Meanwhile, France was typically referred to as “[t]Zarfat” (alt. “Sarfat”) in by Sephardim; yet–tellingly–it seems never to have been referred to as such by the Ashkenazim.

How did Ashkenazi Jews refer to Sephardic Jews—and, for that matter, to the regions known as “Sepharad” and “Zarfat”—in the 11th thru 14th centuries? It’s safe to assume that if there were exonyms in one direction, there were exonyms in the other direction. The Ashkenazim clearly thought of France in different terms than the Sephardim, who had been there since Late Antiquity. It would make no sense that Sephardic Jews who (hypothetically) ended up in the Rhineland suddenly, and for no apparent reason, to stop referring to France by the name that had always been used by their forebears.

The Jewish people who came to be known as “Ashkenazim” had a decidedly different perspective on the various languages of their Jewish brethren to the west (i.e. in France). Had they COME FROM France, surely they would have exhibited traces of Zarfatic (and/or Ladino) in their tongue. No such linguistic residue exists in Yiddish.

The question, then, is: Did Ashkenazim use different terminology than Sephardim when it came to referring to, well, Sephardim (as well as to France and the Iberian peninsula)? This is something to look into. Tellingly, Sephardim referred to Ashkeanazim as “Jews from the Caucuses”, “Yehudim Kuzari”, and—pejoratively—as “Tudesco”.

And what of Sephardim who (eventually) DID end up coming into Eastern Europe? Lo and behold: The surname “Vlach” / “Bloch” was the Old Slavic term for “foreigner”, which seems to have been used to refer to those in Ashkenaz who hailed from the Italic peninsula or somewhere else from southeastern Europe (possibly the Balkan peninsula, Wallachia, or the Danubian Plain). Clearly, Jewish people coming from elsewhere in Europe were not thought of as being of the same ethnic background…even as they eventually came to be part of the greater Ashkenazi community.

The onomastics of the Ashkenazim is exactly what we would expect given where they came from and where they ended up.

It’s worth recalling that during the Middle Ages, the only other notable language spoken by Jews in Eastern Europe was the Kara-im language, which was the product of efforts to meld medieval Hebrew with…you guessed it: Turkic. This would make no sense unless Turkic was an autochthonous linguistic element (that is: the lingual starting point for the indigenous population).

Note that Kara-im dialects like Halych (in Galicia-Volhynia; now western Ukraine) and Troki (in Lithuania) are distinct from the Crimean Tatar dialect. (As is Kumen, Kumyk, Kalmyk, Kazan, [Balkan] Kara-chay, and Kara-kalpak; Kara-im is a neo-Kipchak language.) When it comes to Jews who speak Kara-im, the point is simple: There would have been no reason to try to meld the liturgical language of Judaism with Turkic languages had there not been a significant number of Turkic Jews (i.e. Jews who’s incipient tongue was Turkic) that warranted doing so.

And what of the southern-most part of the Pale of Settlement? As it happens, the Krymchaks (a.k.a. Jewish Tatars; spec. the Crimean Karaites) STILL use a Judaic tongue that has distinctly Turkic roots. {31}

All this is yet more corroboration of the present thesis. It shows that any contention that the Ashkenazim primarily emerged in northeastern Europe due to an EASTWARD migration of Jews from the WEST (prior to the 11th century) is fallacious.

Another point worth noting: If the majority of Ashkenazim had originally hailed from the west / south of “Ashkenaz”, they likely would have done in Germany what Jewish people had done in virtually EVERY OTHER region: created a creolization of Hebrew with the indigenous language. Note that this happened ALMOST EVERYWHERE ELSE that Jews found themselves:

- Lusitanic in Portugal

- Ladino (and its variants: Haketia and Tetuani) primarily in Andalusia. Here, Hebrew melded with Castilian Spanish; with a dash of Arabic and Frankish; and even some Ottoman Turkish and/or Byzantine Greek for those farther east. This was also in the midst of Mozarabic—an Iberian variant of Arabic infused with Galician.

- Zarfatic in Frankish lands (“Zarfat” was the Sephardic name for France) {70}

- Shuadit in Occitania (a distinct variant of Zarfatic used by Rashi)

- Italkian on the Italic peninsula

- Yevanic (Judaeo-Greek; including Romaniot[e] and Karaitika) in Greece

- Gruzinic in Georgia

- Dzhidi / Latorayi (Judaeo-Persian) in Persia; including its offshoot, Bukhori (Judaeo-Tajik; Judaeo-Hamedani) amongst Bukharan Jews in Transoxiana

- Hulaula / Didan (Judaeo-Azeri) in the southern Caucuses

- Lishan[a] Deni (Judaeo-Kurdish) in Nineveh

- Judaeo-Arabic in Palestine; including Judaeo-Yemeni in southern Arabia (often referred to as “Te[i]mani”)

Those are a dozen of the most well-known instances. ALL had a Hebraic substrate. Amongst Mizra[c]him (Arab Jews), communities also melded Hebraic vernaculars with Berber (in the Maghreb). And in Mesopotamia, they even melded Hebrew with its antecedent, Aramaic, yielding Yahudic (Judaeo-Aramaic).

Also notable is Judeo-Tat (a.k.a. “Juhuri”; “Juvuro”), which later emerged in the Caucasus (and closely resembles the aforementioned “Didan”). That was a synthesis of Middle Persian and Sogdian; and was effectively a creolization resulting from the centuries of commerce along the Silk Road. This illustrates the fact that there were alternatives to Yiddish available to the [k]Hazarian diaspora.

Another illustration of a cultural confluence was the Alans: a Perso-Turkic people from the Eurasian Steppes whose language was ALSO a synthesis of Middle Persian and Sogdian. As it happens, they originated in the north Caucuses as well; and—via modern-day Ukraine—they migrated to Europe (though farther to the south than did the [k]Hazars).

Wonder how far a Turkic people could have made it into Europe? Behold the Alans, who made it all the way to the Iberian Peninsula. (!) The Alans did not change their identity during their migration westward; as they had no reason to do so. Though they DID shed their original identity as “Aryan[a]”—the etymological basis for their ethnonym, which was also the basis for the Sarmatian “Rhoxolani” and “Alanorsoi”. {64}

The [k]Hazars were not the only Turkic people to undergo an identity reboot upon arriving in Europe. The Gagauz, who’s Turkic ancestors were the Kutrigurs / Utigurs of the Pontic Steppes, have considered themselves European Christians for many centuries. Meanwhile, the Ossetians (of the Caucuses) have Alanic provenance; yet they no longer consider themselves Turkic. The Ossetian tongue is a hybridization of Persian (likely due to Sogdian) and Old Turkic. Modern Hungarians (Magyars) have embraced an explicitly Occidental identity, having shed any allegiance to their Turkic provenance (see Postscript 1).

Hybridization with Semitic antecedents was clearly the prevailing trend wherever Jews happened to settle over the centuries. Yet–remarkably–such lingual hybridization did NOT happen with the Ashkenazim. Are we to suppose that this is some uncanny coincidence?

This exception is especially odd, as a creolization of Hebrew with Slavic DID (fleetingly) exist: Knaanic. For the Ashkenazim, the fact that Yiddish prevailed over Knaanic is very telling. It means that the Jews of the German lands most likely derived their lingua franca from some OTHER hybridization (to wit: German was melded with a non-Semitic tongue…with which they were more familiar than even Slavic).

The most interesting case is the emergence of Yevanic in Anatolia, which had Semitic (mostly Aramaic) elements, yet also incorporated TURKIC elements. (“Yevan” / “Yawan” was the Biblical name for Greece, likely a variation on “Ionia”.)

Yevanic seems to have originated in Chalkis (a.k.a. “Negroponte”) amongst Hellenized Jews, so may have merged with the language used by Jews in Anatolia at some point during the Middle Ages. Note that inscriptions from much earlier, such as those in Thessalonika (e.g. the synagogue of the agora in Athens) and on the island of Delos, were Samaritan, not Judaic.

The Romaniote Jews were always distinct from Sephardim. Tellingly, “Romaniote” derives from the medieval term for the Byzantines: the “Rhomaioi”; which means that particular Jewish identity would have been established at some point in Late Antiquity.

Another query is worth posing: Did there arise any instances in which Sephardim felt obliged to adapt their endogenous Hebraic vernacular to an indigenous Turkic language? As it turns out: yes. Lo and behold: Sephardic Jews hybridized Hebrew and Azeri–yielding the creole tongue listed above: Didan, which is used by Sephardim who ended up in what is now Azerbaijan.

This corroborates the fact that, even when adopting new vernaculars, Sephardim ALWAYS retained the Hebraic linguistic element of their Semitic forebears. It comes as no surprise, then, that Sephardim in the Rhineland ESCHEWED Yiddish even as Ashkenazim in the Rhineland EMBRACED it.

Both Juhuri and Lishan Deni (Didan) demonstrate what happens when Sephardim incorporate Turkic into a Semitic vernacular. Were the Ashkenazim originally Sephardic, they would have done the same sort of thing. What was done by Azeri Jews, who had a Sephardic background shows what WOULD happen were Sephardim to have mixed a Hebraic tongue (like Ladino or Zarfatic) with a Turkic tongue. Yet no Hebraic hybridization occurred amongst the Ashkenazim. Yiddish, which is essentially a de facto Judeo-German, exhibits palpable traces of the Turkic origin of its speakers.

Note that, amidst all of this, Sephardim were still composing material IN HEBREW through the 12th century—as attested by chronicles of the Rhineland massacres by the Tosafists, Solomon ben Simson and Eliezer ben Nathan (both of Mainz).

It is worth noting that there is a smattering of Slavic elements in Yiddish. For example, in Yiddish, “koval” became slang for “maverick”. It seems to have been a variation on the Old Slavic term for blacksmith: “kuznets” (which, it turns out, was also used as an Ashkenazi surname). Shall we conjecture that Sephardim migrated from the Iberian peninsula, France, and/or the Balkans into Slavic lands and subsequently–during the Renaissance–incorporated that region’s lexemes into their already-established vernacular? It is feasible. But with regard to this particular case, doing so would not have made much sense; as the Hebrew term for blacksmith had long-been “napa[k]h”–as in Isaiah 41:7, 44:12, and 54:16 (also used in First Samuel 13:19). Meanwhile, the Saxon term for blacksmith was “schmied”, the basis for “schmidt”; which became a popular Ashkenazi surname. If the Ashkenazim had emerged as a distinct community due to a SCHISM (a separation from Sephardic forebears), we would need to conjecture that the Hebraic term was jettisoned in favor of these other (foreign) terms–a scenario that seems far-fetched. It is far more likely that, upon arriving in Eastern Europe, the [k]Hazarian diaspora eschewed the Turkic term “tarkhan” in favor of the Slavic “koval” and Germanic “schmied” as they asserted their new ethnic identity.

Bottom line: The so-called “split” between the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim in north-central Europe is a myth. There is no evidence for a schism in Beth Israel in that region—or in ANY region—at that point in time. {108} As it happens, there’s only one other explanation for two disparate versions of the creed suddenly finding themselves in proximity to one another: Two pre-existing Jewish communities ENCOUNTERED each other…either by one or both of them migrating to the region in which the encounter took place. The Sephardim had already been in Western Europe for many, many centuries. The new arrivals must have come from somewhere else. (Hint: They didn’t come from the North Pole.)

In the 16th century, there was finally a (doctrinal and ethnic) reconciliation between these two Jewish communities with disparate provenance—that is: between the “Beit [house of] Joseph Karo” (Sephardic / Talmudic) and the “Darchei [way of] Moses Isserles” (Ashkenazi / non-Talmudic) via the former’s “Shulchan Aruch”. There would have been further motivation for this reconciliation that that point is history, as European Jewry was in the midst of a series of pogroms from Andalusia to “Ashkenaz”. Not only was the Spanish Inquisition carrying out its horrors across the Iberian Peninsula (following the expulsion of Jews in 1492), there was systematic persecution of Jews in Germany beginning c. 1509. Such tribulation would have likely prompted a call for solidarity across the Sephardic-Ashkenazi divide. It was time for Beth Israel to unite.

Other clues are worth considering. In the 10th century, a [k]Hazarian Jewish community, which had settled in what is now the Kievan “Podil” (in Ruthenia, along the Dnieper River; formerly the land of the Polans; which, by that time, was ruled by Kieven Rus), penned a letter using Old Turkic runes. In this Kievan letter, the authors signed off with the hallmark [k]Hazar “hokurüm”: “ilik” [I read it thus]. (Ref. Norman Golb and Omeljan Pritsak’s “Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century”; Peter B. Golden’s “The World Of The Khazars”.) Behold a distinctly Jewish document with signature [k]Hazar features.

What else happened in the late 10th / early 11th century? Another Turkic language (that of the Magyars: Old Hungarian) adopted the Roman script, even as it retained much of its old vernacular. This transition occurred at the behest of Grand Prince, Stephen (ref. the chronicles of Simon of Keza). Other Turkic tribes made a transition from Old Turkic runes to a more Occidental (i.e. European) orthography–as with the Esegel Bulgars, who may have been affiliated with the [k]Havars (ref. the “Zayn al-Akhbar” by Abu Said Abd al-Hayy ibn Zahhak of Gardiz). This occurred in the lower Volga area–in Pannonia (by the Carpathian Basin). These other case-studies demonstrate that Turkic peoples who found themselves in the Occidental orbit ended up shedding much of their Turkic heritage; though vestiges remain if we care to look. (The “catch”, of course, is that not everyone cares to look.) {76}

In terms of disjunctive literary heritage, we might consider the circulation of the “Meshal ha-Kadmoni[m]” [Fables of the Ancients] by the Sephardic author, Isaac ben Solomon “Ibn Sahula” of Castile. The book was composed in the 13th century; yet the work was not rendered in Yiddish until the last decade of the 17th century–over four centuries later! Had Ashkenazim been familiar with these fables all along, then why the long delay in translating it into their lingua franca? Recall that Yiddish material had been in use since at least as far back as the 14th century, when Ashkenazim composed the “Shmuel-bukh” and “Dokus Horant” discussed earlier.

We might also note that the “piyyut” (Jewish liturgical poem) known as “Akdamut” [Aramaic for “Introduction to the Words”] is recited by Ashkenazim–but not by Sephardim–on Shavuot. Supposedly, it was originally composed by Meir ben Isaac (also known by the sobriquet: “Nehora[i]”, which is the Aramaic term for “light”) while he was the cantor at Worms…so the story goes. However, this is probably an urban legend, as it was reputed to have been written AFTER his son was killed in the riots of the first Crusade (that is: after the spring of 1096). Meir is said to have died in 1095.