The History Of Female Empowerment II: Women of Battle, Women of Letters

December 7, 2019 Category: History

Writers and Intellectuals

There are several metrics by which the degree of enfranchisement might be determined. As demonstrated by the Sumerian goddess of writing / learning, Nisaba, wisdom has often been associated with the feminine since the Bronze Age. This was attested during Classical Antiquity by the prominence of Athena and Minerva. In Late Antiquity, Gnostics posited “Sophia” as a feminine form of the divine (associated with divine knowledge).

Women have often been accorded esteem according to their intellectual prowess for millennia. So now let’s survey prominent female THINKERS of history. I will limit this survey to the pre-Enlightenment era; as there was an explosion of figures after c. 1700. (The next essay–part three in this series–will explore female luminaries thru the early 20th century.) For now, let’s assume that the incidence of influential female writers / scholars can also be used as an index for the esteem accorded to women in any given society. In the spirit of Calliope (Greek) and Saraswati (Hindu), our survey will predominantly feature writers.

In the 1670’s, French philosopher, François Poullain de la Barre explicitly addressed his female readers, stating: “The [analytic] mind has no sex whatsoever. You are endowed with Reason. Use it. And do not sacrifice blindly to anyone.” Unfortunately, this was not a common sentiment at the time; yet, as we’ll see, it is an insight that dates back to time immemorial. The annals of (recognized) great female minds goes back to the fabled Egyptian physician, “Merit Ptah” c. 2700 B.C. The Sumerian / Akkadian high priestess, En-hedu-ana from the 23rd century B.C. is also worth noting; as she was evidently a respected orator at the time. The female scribe, Amat-Mamu earned renown in Sippar in the 18th century B.C. Meanwhile, the Indian philosopher, Lopa-mudra (a.k.a. “Kaushi-taki” / “Vara-prada”) from the 15th century B.C. is celebrated to the present day. And the Babylonian high priestess, Tapputi “Belatekallim” was a renown scientist c. 1200 B.C.

Reverence for females as sources of wisdom was common in ancient Egypt. The 11th century B.C. saw the high priestess, Maatkare Mutemhat memorialized for posterity. The 10th century B.C. saw numerous revered priestesses–including Gautseshen, Henut Taui, Karomama Meritmut, Neskhons, and Nesitanebetashru. The 9th century B.C. brought the high priestess, Meresamun. The 8th century B.C. brought the high priestesses, Shepenupet I & II. And the high priestess, Nitokris, rose to prominence in the late 7th century / early 6th century B.C.

In Abrahamic lore, there was Esther of Persia–who leveraged her political standing to save the Maccabees from the dastardly Amalekite vizier, “Haman”. This reminded us that, even in a patriarchal religion, powerful women could hold sway over the affairs of men.

Let’s take a look at Classical Antiquity. Female spirits seen as the source of wisdom / inspiration goes back to the Greek muses. We find a similar motif with the Buddhist “dakini”. The list of renown poetesses from ancient Greece alone is quite long. Here are a dozen of the most celebrated:

- Korinna of Tanagra (Boeotia)

- Myrtis of Anthedon (Boeotia)

- Telesilla of Argos

- Sappho of Lesbos

- Erinna of Rhodes

- Cleobulina of Rhodes

- Praxilla of Sicyon

- Nossis of Locri (Calabria)

- Melinno of Locri (Calabria)

- Anyte of Tegea

- Myro / Myra [Moero / Moera] of Byzantium

- Cleitagora of Sparta

It is no secret that women have been involved in literary affairs for millennia. Indeed, women from Classical Antiquity were more than just poets. There were scholars (publicly recognized intellectuals) as well. In ancient Greece alone, there was:

- Theano of Croton(a) [possibly of Thurii or Crete] (Pythagorean philosopher in the late 6th century B.C.)

- Cheilonis of Sparta (Pythagorean philosopher in the late 6th / early 5th century B.C.)

- Tyrsenis of Sybaris (Pythagorean philosopher in the late 6th / early 5th century B.C.)

- Damo and Arignote of Croton(a) (both Pythagorean philosophers in the late 6th / early 5th century B.C.)

- Gorgo of Sparta (influential politician in the late 6th / early 5th century B.C.)

- Aspasia of Miletus (Ionian Pythagorean philosopher in the 5th century B.C.)

- Diotima of Mantinea (Arcadian Pythagorean philosopher in the 5th century B.C.)

- Arete of Cyrene [Kyrenaika] (Libyan Pythagorean philosopher in the early 4th century B.C.)

- Lastheneia of Mantinea (Platonic philosopher in the early 4th century B.C.)

- Axiothea of Phlius [Argolis] (Platonic philosopher in the early 4th century B.C.)

- Agnodike and Metrodora of Athens (both physicians in the 4th century B.C.)

- Hipparchia of Maroneia (Cynic philosopher in the late 4th / early 3rd century B.C.)

- Aesara of Lucania (Pythagorean philosopher in the late 4th / early 3rd century B.C.)

- Anyte of Tegea (Arcadian poet in the early 3rd century B.C.)

- Themista and Leontion of Lampsacus (both Epicurean philosophers in the 3rd century B.C.)

- Ptolemais of Cyrene (Pythagorean scientist in the 2nd century B.C.)

- Aglaonike of Thessaly (astronomer in the late 2nd / early 1st century B.C.)

…to name twenty of the most renown before the common age. We might also note Pamphile of Epidaurus, who was a renown female historian in the 1st century A.D.

This is not to say that everything was hunky-dory for the Hellenic everywoman. Far from it. What records of these exceptional women indicate, though, is that there were circumstances in which women were accorded esteem based on their intelligence (as opposed to, say, simply being the wife / daughter of a famous man). Put another way: These women were respected for more than just their beauty or their usefulness to an otherwise patriarchal order.

Women were sometimes allowed to rise to prominence–and make important contributions to society–in ancient Greece because of their minds (rather than merely because they were well-connected). Here are 33 more notable female thinkers through Late Antiquity:

- Indian (Kosala) philosopher, Gargi-Vachaknavi of Vaidaha c. 700 B.C.

- proto-Korean poet, Yeo Ok of Go-joseon (7th century B.C.)

- Chinese poet, Lady Xu Mu (7th century B.C.)

- Persian (Achaemenid) Queen [“Shahbanu”] Amitis (6th century B.C.)

- Persian (Achaemenid) Persian business-woman, Irdabama (5th century B.C.)

- Celtic (Galatian) political leader, Onomaris (4th century B.C.)

- Persian (Parthian) queen [“Shah-banu”], Azadokht (3rd century B.C.)

- Chinese (Han) poet, Zhuo Wenjun (2nd century B.C.)

- Roman intellectual, Cornelia Africana (2nd century B.C.)

- Roman political activist, Hortensia (1st century B.C.)

- Roman historian, Pamphile of Epidaurus (1st century A.D.)

- Roman satirists, Sulpicia I & II (1st century A.D.)

- Gallo-Roman physician, Aemilia “Hilaria” of Austrasia (1st century A.D.)

- Persian (Parthian) secretary of the treasury, Artadokht (1st century A.D.)

- Roman writer, Julia Balbilla (late 1st / early 2nd century)

- Chinese historian, Ban Zhao (late 1st / early 2nd century)

- Roman empress, Julia Domna (late 2nd / early 3rd century)

- Egyptian chemist, Cleopatra the Alchemist (3rd century)

- Greco-Roman physician, Metrodora (3rd century)

- Japanese high priestess, Yamatohime no Mikoto (c. 300)

- Roman (Christian) writer, Faltonia Betitia Proba (4th century)

- Chinese (Eastern Jin) scholar, Xie Daoyun of Henan (4th century)

- Byzantine physician, Aspasia (4th century)

- Egyptian pedagogue, Pandrosion of Alexandria [possibly apocryphal] (4th century)

- Egyptian philosopher, Aedesia of Alexandria (5th century)

- Egyptian philosopher / pedagogue, Hypatia of Alexandria (5th century)

- Persian (Sassanid) politician and jurist, princess Parin (5th century)

- Chinese (Southern Qi) poetess, Zu Xiao-xiao of Qian-tang (5th century)

- Chinese poetess, Han Lan-ying of Wu (5th century)

- Indian matriarch of Zen Buddhism, Prajnadhara [Bodhidharma] (5th century)

- Gallo-Roman satirist, Eucheria of Aquitania (late 5th / early 6th century)

- Indian (Tamil) spiritual icon, Karaikal Ammaiyar (6th century)

Note as well the prominent role women played in the Seleucid Empire–especially Queens consort Laodice of Pontus, Laodice of Macedonia, and Laodice I-VII, each of whom wielded prodigious political power.

There were well-known female poets in pre-Islamic Arabia–most notably the poetess, Afira bint Abbad in the 3rd century and Layla bint Lukayz in the 5th century. There were at least SEVEN well-known female poets in Arabia during Islamic prophet, Mohammed’s lifetime:

- Al-Khirniq bint Badr

- Safiyah bint Thalabah al-Shaybaniyah of the Banu Shayban (a.k.a. “Al-Hujayjah”)

- Qutayla ukht al-Nadr of the Banu Quraysh (possibly from Ta’if)

- Hind bint al-Numan of the Banu Lakhm (a.k.a. “Al-Hurqah”)

- Asma bint Marwan; assassinated at the behest of MoM for speaking out against him (ref. Ibn Ishaq’s “Sirat Rasul Allah”).

- Jewish poetess, Sarah of Yemen (of the Banu Qurayza); assassinated for speaking out against MoM.

- Al-Khansa of Najd; lived until c. 645, and is said to have become a Mohammedan later in her life. Presumably, being a poet, she did not have much of a choice in the matter…if, that is, she wished to continue in her vocation and live. {6}

Prominent female writers in the Far East from the late 6th thru 9th century included:

- Japanese princess, Nukata (late 6th / early 7th century)

- Japanese Empress, Yamato no Okimi (late 6th / early 7th century)

- Chinese poet, Xu Hui (late 6th / early 7th century)

- Chinese courtesan, Shangguan Wan’er (late 6th / early 7th century)

- Chinese Empress, Zhangsun (late 6th / early 7th century)

- Chinese (Tang) rebel leader, Chen Shuozhen of Muzhou (7th century)

- Chinese (Tang) poet, Xu Hui of Huzhou (7th century)

- Japanese Empresses, Jito no Tenji and Yamato Hime no Okimi (7th century)

- Japanese princess, Oku [a.k.a. “Saio”] (late 7th century)

- Chinese (Tang) Empress Wu Zetian (late 7th century)

- Indian (Tamil) “Alvar” [sage] and author, Andal of Srivilliputhur (late 7th / early 8th century)

- Indian natural philosopher, Gargi Vachaknavi of Bihar (late 7th / erly 8th century)

- Japanese Empress Genmei (early 8th century)

- Japanese poet, Otomo no Sakanoue no Iratsume (early 8th century)

- Chinese (Tang) poets, Xue Tao and Yu Xuanji (late 8th / early 9th century)

- Japanese poets, Ono no Komachi and Kodai no Kimi (9th century)

- Chinese poet, Song Ruo-shen of Hebei (9th century)

Also note the Armenian poetess, Khosrov-i-dukht (8th century), as well as the renown Byzantine poet and composer, Kassia of Constantinople and Frankish writer, Dhuoda of Septimania (from the 9th century). The Muslim world had no equivalent.

A disparity between women of letters in the non-Muslim world vis a vis the Muslim world is impossible not to notice. The only possible exception here would have been an 8th-century poetess named Maria Alphaizuli of Silva (Lusitania, in western Andalusia), who was retroactively given an Arab name: Mariam [bint Yaqub] ash-Shilbi so as to advertise her Moorish identity. Whether or not she was even Muslim is unknown; though it is doubtful. She spent most of her career in Seville.

Tales are also told of the Muslimah “mu-fassir”, Jana Begum bint Abdul Rahim Khan of Delhi, who was employed under Mughal Emperor, Akbar the Great (17th century); and of the Muslimah “mu-haddith”, Fatima bint Hamad al-Fudayliya of the Hijaz (late 18th / early 19th century).

Within Dar al-Islam during the late 8th / early 9th century, the most renown writer was the Qurayshi love-poet, Umar ibn Abi Rabia al-Makhzumi. Also in the early 9th century, the Abbasid princess, Ulayya bint al-Mahdi was said to have composed some love poetry.

Once we get past Mohammed’s ornery declarations about the deficiency of a woman’s mind in Bukhari’s Hadith (upon being asked why a woman’s testimony is worth half that of a man), the explanation for the dearth of female luminaries in Dar al-Islam becomes plain to see.

(MoM is also said to have averred that the proof of a woman’s intellectual deficiency is that the witness of two woman is equal to that of one man. It is difficult to decide which is more risible: the circular reasoning or the misogyny.)

From c. 900 to c. 1600, many female luminaries are worth noting. The most renown Renaissance women included:

- German author (and outspoken freethinker), Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim (10th century)

- Persian (Samanid) poetess, Rabia bint Ka’b al-Quzdari of Balkh / Khorasan [a.k.a. “Rabia Balkhi”] (10th century) {1}

- Kashmiri (Vajrayana Buddhist) sages, Sukhasiddhi and Niguma [who founded the Shang-pa Kagyu school] (late 10th / early 11th century)

- Andalusian poetess, Nazhun al-Garnatiya bint al-Qulai’iya of Granada (11th century)

- Andalusian (Jewish) poetess, Qasmuna bint Isma’il (11th century)

- Italian political rebel, Matilda of Canossa [a.k.a. the “Grand Contessa”] (11th century)

- Chinese poetess, Lady Li Qingzhao [a.k.a. Yi’an Jushi] (late 11th / early 12th century)

- Byzantine chronicler, Anna Comnena (early 12th century)

- Italian physicians, Adelle Saracinensa [a.k.a. “Adelle of the Saracens”] and Trota [a.k.a. “Trotula”] of Salerno (12th century)

- German polymath, Hildegard of Bingen (12th century)

- Persian poetess, Mahsati Dabira of Ganja[vi] (12th century)

- Mesopotamian (Jewish) scholar, [?] bat Samuel ben Al-Dastur of Baghdad [a.k.a. “Bat ha-Levi”] of Baghdad (12th century)

- Andalusian poetess, Hafsa bint al-Hajj ar-Rakuniyya of Granada (12th century)

- Andalusian legal scholar, Habiba of Valencia [a.k.a. “Thoma”] (12th century)

- Indian (Kannada / Bhakti) writer and feminist, Akka Maha-devi of Udugani / Karnataka (12th century)

- Mongol (Karaite) “Khatun” [and renown intellectual], Sorghaghtani “Beki” (12th century)

- Chinese restauranteur, Song Wusao of Hang-zhou (12th century)

- French (Britton or Norman) writer, Marie of France (late 12th / early 13th century)

- French physicians, Jacobina Félicie and Magistra Hersend (13th century)

- Italian (Jewish) biblical commentator, Paula Dei Mansi of Verona (13th century)

- Japanese Zen master, Mugai Nyodai (13th century)

- Chinese (Yuan) poetess, Guan Dao-sheng (late 13th / early 14th century)

- Chinese poetess, Zheng Yunduan [a.k.a. “Zhengshu”] (14th century)

- Italian (Roman Catholic) theologian (and political / religious power-broker), Catherine of Siena (14th century)

- Italian physicians, Alessandra Giliani of Emilia-Romagna, Adelmota of Carrara [originally of Padua], Abella of Salerno, Mercuriade of Selerno, and Rebecca de Guarna of Selarno (14th century)

- French physician, Sara of Sancto Aegidio / St. Gilles (14th century)

- Indian (Telugu) princess, Ganga-devi [a.k.a. “Gangambika”] (14th century)

- Indian (Telugu) stateswoman, Nayakuralu Nagamma of Palanadu (14th century)

- Serbian poetess, Jelena Mrnjavcevic [a.k.a. “Jefimija”] (14th century)

- Chinese (Ming) writer, Empress Xu Yihua [a.k.a. “Renxiaowen”] (late 14th century)

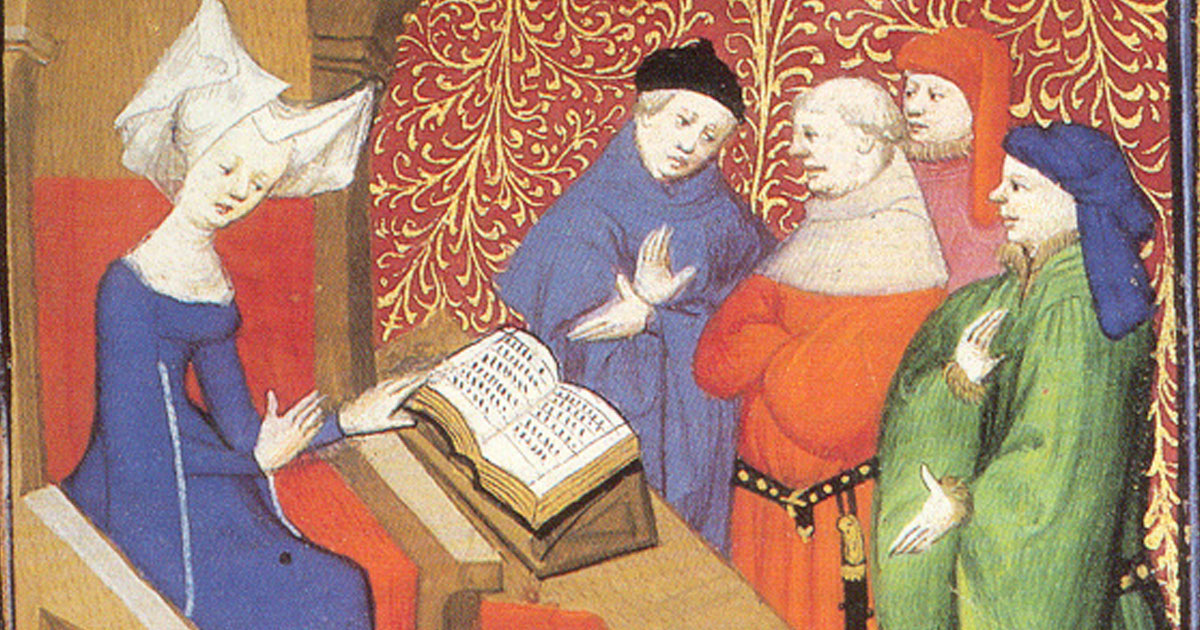

- Italo-French writer, Christine of Pizan (late 14th / early 15th century)

- Italian scholar of medicine, Dorotea Bucca of Bologna (late 14th / early 15th century)

- Andalusian memoirist, Leonor Lopez of Cordoba (late 14th / early 15th century)

- English memoirist (and freethinker), Margery Kempe (late 14th / early 15th century)

- French novelist, Elisabeth of Nassau-Saarbrucken (15th century)

- French reformer, Marguerite of Navarre (15th century)

- Italian (Venetian) feminist / humanist writers, Isotta and Angela Nogarola; as well as Laura Cereta (15th century)

- Castilian (Spanish) writer, Florencia del Pinar (15th century)

- Castilian (Spanish) memoirist, Teresa de Cartagena of Burgos (15th century)

- Icelandic political leader, Olof Loftsdottir (15th century)

- Indian (Telugu) poetesses, Tallapaka Tirumalamma [a.k.a. “Timmakka”] and Atukuri Molla (15th century)

- English writer, Laura Cereta (15th century)

- Welsh poetess, Gwerful Mechain (late 15th century)

- Italian (Venetian) scholar, Cassandra Fedele (late 15th / early 16th century)

- French writer, Anne of France [a.k.a. “Madame la Grande”] (late 15th / early 16th century)

- Spanish pedagogue and humanist, Beatriz Galindo of Salamanca [a.k.a. “La Latina”] (late 15th / early 16th century)

- Italian stateswoman and poetess, Veronica Gambara (16th century)

- French (Huguenot) political leader, Jeanne d’Albret (16th century)

- French (Walloon) religious reformer, Marie Dentière of Tournai (16th century)

- Korean physician, Jang Geum (16th century)

- Korean poetesses, Shin Saimdang and Heo Nanseolheon (16th century)

- Chinese (Ming) poetesses, Duan Shuqing and Huang E (16th century)

- Indian (Kannada / Bhakti) poetess, Mira-bai of Rajasthan (16th century)

- French novelist, Marguerite Briet of Abbeville [a.k.a. “Hélisenne de Crenne”] (16th century)

- French writers who stood up for female empowerment, Nicole Estienne and Louise Labé (16th century)

- French philosopher, Claude de Bectoz of Dauphiné (16th century)

- French humanist and religious reformer, Marguerite of Navarre / Angoulême (16th century)

- English writers, Jane Anger and Isabella Whitney (16th century)

- English historian, Anne Dowriche (16th century)

- English commentator (and iconoclast), Anne Ayscough [a.k.a. “Askew”] (16th century)

- Danish businesswoman, Ingeborg Skeel of Vendsyssel (16th century)

- Italian polymaths, Loredana Marcello of Venice and Olympia Fulvia Morata of Ferrera (16th century)

- Italian poets, Vittoria Colonna, Laura Terracina, Laura Battiferri, and Tullia d’Aragona (16th century)

- Italian (Venetian) writers (who stood up for female empowerment), Moderata Fonte [a.k.a. “Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi”] and Lucrezia Marinella (16th century)

- Spanish professors, Isabella Losa, Luisa de Medrano, and Francisca de Lebrija (16th century)

- German postmaster, Katharina Henoth of Cologne (late 16th / early 17th century)

- French mathematician, Catherine de Parthenay (late 16th / early 17th century)

- English writers, Mary (née Sidney) Herbert [Countess of Pembroke] and her niece, Mary Wroth; Elizabeth Cary [Viscountess Falkland]; and Aemilia (née Bassano) Lanier (late 16th / early 17th century)

- Dalmatian (Croatian) poetess, Cvijeta Zuzoric of Dubrovnik / Ragusa (16th / early 17th century)

Note that the women who earned notoriety in Mesopotamia and Persia were not Muslim. Most interestingly, of the five women who earned notoriety in Andalusia between c. 1000 and c. 1400, all were non-Muslim.

This brings us to the 17th century. Here are 25 of the most notable luminaries:

- Mesopotamian rabbi, Asenath Barzani of Mosul

- Scottish poetess, Elizabeth Melville

- Dutch polymath, Anna Maria van Schurman

- Dutch poetess, Anna Roemers Visscher of Amsterdam

- Swedish polymath, Wendela Skytte

- Swedish post-master, Gese Wechel

- English polymath, Margaret (née Lucas) Cavendish [Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne]

- English philosophers, Judith Drake and Anne Conway

- English political writers, Jane Barker, Rachel Speght, and Bathsua Reginald Makin

- English writers, Aphra Behn, Elizabeth Cary [Viscountess of Falkland], Jane Cavendish, Katherine Philips, Mary Chudleigh, Anne Killigrew, Rachel Speght, Mary Wroth, Mary Herbert (née Sidney) [Viscountess of Pembroke], Margaret Fell, and Susanna Centlivre

- Mexican writer, Juana Inés de la Cruz

- French writers, Madeleine de Scudéry, Catherine Bernard, and Marie-Madeleine Pioche de La Vergne (a.k.a. “Madame de La Fayette”)

- British-American writer, Anne Bradstreet

- Swiss naturalist, Maria Sibylla Merian

We might ask: Were these women part of a trend or were they mere aberrations? Alas, it is difficult to determine the extent to which they were outliers in their respective societies; as history tends not to record the quotidian lives of common-folk. Be that as it may, any society in which women could rise to prominence, and earn ANY acclaim, says something about the ambient culture. Note, for example, the prominent role of the “iya-l-awo” / “mama-l-awo” (female diviner) in the Ife Faith of the Yoruba.

At the beginning of the 15th century, Christine of Pizan argued that women–as fully rational beings–could be virtuous leaders; and that a virtuous woman in power could beget a virtuous polity. She argued for the enfranchisement of women; and promoted the education of women. It is difficult to imagine this being done in the Muslim world.

The women enumerated here were, indeed, considered exceptional; yet the fact remains that they were accorded prodigious social status AS WOMEN in their society. That’s not nothing.

Medieval Japanese culture also offers a point of reference. Between the late 9th and 13th centuries (i.e. Islam’s “Golden Age”), renown female writers from Japan alone included:

- Lady Ise no Miyasudokoro (late 9th century)

- Kiyohara no Nagiko [a.k.a. “Sei Shonagon”] (late 9th / early 10th century)

- Nakatsukasa, Kishi Joo, and Michitsuna no Haha (10th century)

- Murasaki Shikibu, Akazome Emon, and Uma no Naishi (late 10th / early 11th century)

- Ise no Taifu and Izumi Shikibu (early 11th century)

- Taira no Nakako [a.k.a. “Suo no Naishi”] (late 11th / early 12th century)

- Oto-jiju no Minamoto no Yorimitsu [a.k.a. “Sagami”], princess Shikishi, and Inpumon-in no Tayu (12th century)

- Fujiwara no Shunzei [no Musume] and Gishumon-in no Tango [no Zenni] (late 12th / early 13th century)

- Go-Toba-in no Shimotsuki [a.k.a. “Shinno”] and Kayomon-in no Echizen [a.k.a. “Ise no Nyobo”] (13th century)

Murasaki Shikibu of Kyoto (a courtesan of the Fuji-wara clan) introduced the world to the novel with “The Tale of Genji” (c. 1000). {8} It is unclear whether or not this was the author’s real name–as she and the tale’s protagonist have the same name. This could either be because the author named the primary female character after herself OR because the author adopted the character’s name as a pseudonym.

The first notable case of a female pedagogue rising to prominence in the Muslim world was a Zaydi (Shiite) Tunisian woman named Fatima al-Fihri of Kairouan–who helped found the “Al-Qarawiyyin” madrasah in Fes, Morocco c. 859 under the aegis of the (Shia) Idrisid Dynasty. {3} The next two notable women in the Muslim world were quasi-scholars: Lubna of Cordoba and Fatima of Madrid–both in Andalusia during the late 10th century. Bear in mind that these women were notable because they were so extraordinary; not because they were indicative of a burgeoning feminist trend in Dar al-Islam. Attributing their scholarship to Islam would be to confuse “because of” with “in spite of”. (For more on this, see the Appendix below.)

This survey mustn’t be misconstrued as an attempt to obfuscate the patriarchal systems that prevailed around most of the world most of the time throughout history. The point here is to highlight where and when marginal headway was made. One way to do this is to use iconic female figures as an indication of watershed developments. Such instances of female prominence were, of course, sadly circumscribed. Even so, they are worth noting. What makes these figures so impressive is that it was much more difficult for women to achieve anything of note. After all, they were generally up against patriarchal systems–replete with structural inequality and systemic misogyny.

Moreover, women had to contend with many things men did not: the dangers of pregnancy and childbirth, the burdens of monthly menstruation, comparative physical weakness, etc. {7} The fact that these women were able to overcome adversity (normalized sexism surely served as a formidable obstacle in most cases) is nothing short of extraordinary. It behooves us to wonder: How many more women would have realized their full potential–and risen to prominence–had they been on a level playing field with men? The least patriarchal societies (Sarmatian, Nubian, Persian, Mongolian, etc.) give us a hint.

The point is worth repeating: It is not only rulers to whom we can look (as we did in the previous essay), but to warriors and influential thinkers / writers as well. In no case was augmented piety to thank for any headway that was made. Having surveyed over FOUR HUNDRED female warriors and writers around the world, we find that it is unsurprising that no religious doctrine figured into the U.N. Commission On The Status Of Women when it was convened in 1946. Two years later, when the U.N. drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (under the tutelage of Eleanor Roosevelt), the document did not cite any sacred text. Nobody was surprised by this.

[To be continued. In part III of this series, we will look at mother-goddesses and modern feminists.]

{1 She may be apocryphal, as there is only second-hand reference to her existence. As legend has it, she was murdered by her brother, Hares, for composing love poems to his slave, Baktash.}

{2 Considering a zeitgeist that was suffused with hyper-dogmatism, it is little wonder that alchemy “informed” much of the metallurgical musings that abounded within the Islamic world during its first millennium (as with men like, say, “Munajimm”). The same spurious enterprise occurred in equally-dogmatic (Roman Catholic) Europe. (Even Isaac Newton dabbled in it!) An example is Edward Talbot / Kelley’s “Book of Dunstan”. Notable dissent on the topic eventually came from iconoclasts like Avicenna and, later, Ibn Khaldun. Their dissent was based on neither the Koran nor the Hadith. It was heterodox positions like this that made such men iconoclasts within the Ummah.}

{3 This eventually became the University of al-Karaouine (in 1963). Interestingly, it was founded under a Zaydi (Shia) caliphate–which means that most Muslims today (who are Sunni) would question the legitimacy of EVEN THIS rare occurrence. Incidentally, the same goes for the other well-known medieval Muslim school in North Africa: the Al-Azhar madrasah in Cairo, Egypt (now Al-Azhar University). It was established just over a century later (c. 972) by the Fatimid Dynasty–who were (Isma’ili) Shiites. Note that, in spite of their Shia origins, both are now Sunni-affiliated institutions. That they would not exist but for Shiites is a fact disregarded by their Sunni enthusiasts today. Indeed, if Sunni precedent prevailed, such institutions would have to be voided (and, arguably, would never have come into existence in the first place). For Sunnis to now take credit for the existence of these schools is the height of perfidy.}

{4 Female samurai were sometimes referred to as “onna-bugeisha”. Also note the “kunoichi” (female ninjas), such as those in the Takeda clan during the 16th century.}

{5 Note also that female warriors were common in the Congolese Monomotapa confederacy…a place where nobody had ever heard of the Koran or Hadith.}

{6 In order to persist in her craft, she was thereafter limited to benedictions / elegies for mujahideen, gushing encomia to MoM, and other approved material. There is no telling whether or not her conversion was a savvy career move.}

{7 Certain technological advancements contributed to the emancipation of women: the washing machine, ways to deal with menses in a sanitary way, the birth-control pill, access to safe abortions, sapience regarding childbirth, etc. There was a long, meandering process by which the general populace managed to rise above patriarchal institutions (which were, of course, mostly religious in nature). Major headway was made via suffrage and access to political power; as well as drastically augmented education and employment opportunities.}

{8 Her daughter was the renown poetess, Daini no Sanmi.}

Appendix:

Beyond the question of who I count in these surveys is who I do NOT count; and WHY I don’t count them. Am I falling victim to confirmation bias; and thus being “selective”–either unwittingly or wittingly–so as to support pre-ordained conclusions?

Certain Muslimahs (i.e. many of those often celebrated in Islamic lore) fail to qualify according to the present criteria. Am I rigging the tabulation somehow? Am I applying different standards to Muslimahs and non-Muslimahs? What about Khadijah? {A}

There are a few (apocryphal) tales of females within Dar al-Islam who were “warriors”. Most notable are Ka’b al-Ansariyya of the Banu Najjar (a.k.a. “Nusayba”; a.k.a. “Umm Amarah”) and Khawlah bint al-Azwar [al-Kindiyyah] of the Bani Asad. The first is revered because she carried water to MoM (and allegedly killed an enemy’s horse) during the Battle of Uhud. She is also said to have helped some of the soldiers. The second is revered because her brother, Khalid, was a military commander in the Battles of Yarmuk, Adnajin, and Sanita-al-Uqab; and she supposedly fought alongside the men. {B}

We might note that another storied Muslimah of the Sahabah was Umm Waraqa, who is known for NOT being allowed to fight with men, and instead being charged with leading prayers off the battlefield. She is now celebrated for being a prayer-leader.

Tales of other fabled Muslimah warriors (such as Ghazala al-Haruriyya) are likely apocryphal. (A Muslimah named Khawlah bint al-Kindiyyah is said to have participated in skirmishes against the Greeks in Syria in the 7th century.) In any case, such figures are relatively minor; and of dubious historical authenticity. More to the point: Their feats are–to put it mildly–unimpressive.

We hear about the Yemeni warrior, Ghamra bint Utarid ibn Awf–an enterprising woman who was brought up as a boy, and so carried out tasks normally accorded to men. (Think of the Arab version of the Chinese legend of Mulan.) She supposedly lived under the alias, “Amr”. There were also tales of a “Jayda” posing as a “Jawdar” in the “Sirat Antar”. In addition, there are apocrypha about a Christian warrior-princess named “Marjana” who eventually converted to Islam. So the story goes.

In a twist of irony so outlandish as to elicit a chuckle, tales are told of the wives of the pathologically misogynist cynosure, Abd al-Wahhab–including “Ulwa” and a dauntless Ethiopian warrior-princess named “Maymuna”. Meanwhile, we are told that his daughter, Qannasa bint Muzahim undertook raiding campaigns from her mountain fortress…to capture and seduce her enemies. (Gadzooks!) Even Abd al-Wahhab’s mother, princess Dhat al-Himma of the Banu Kilab (a.k.a. “Fatima”) was re-cast as an intrepid military leader in battles against the Byzantines. It is possible that such tall-tales were concocted to placate Arabia’s oppressed female population: a kind of perverse consolation for their travails in the real world. Lord only knows.

There are plenty of females in the non-Muslim world who actually LED military campaigns–whom I refrain from qualifying in this survey for similar reasons. Historically, they were not significant enough–as with 13th-century crusader, Eleanor of Castile. Also not making the cut: Dutch heroines, Gertruid Bolwater of Venlo, and Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer of Haarlem. Such omissions from the non-Muslim world demonstrate that the criteria for qualification in this survey are consistent.

There are a few (apocryphal) tales of females within Dar al-Islam who were “warriors”. Most notable are Ka’b al-Ansariyya of the Banu Najjar (a.k.a. “Nusayba”; a.k.a. “Umm Amarah”) and Khawlah bint al-Azwar [al-Kindiyyah] of the Bani Asad. The first is revered because she carried water to Mohammed (and allegedly killed an enemy’s horse) during the Battle of Uhud. She is also said to have helped some of the soldiers. The second is revered because her brother, Khalid, was a military commander in the Battles of Yarmuk, Adnajin, and Sanita al-Uqab; and she supposedly fought alongside the men.

We might note that another storied Muslimah of the Sahabah was Umm Waraqa, who is known for NOT being allowed to fight with men, and instead being charged with leading prayers off the battlefield. She is now celebrated for being a prayer-leader.

In cases where they DID happen to be Muslim, women were–at most–clerks for “fuqaha” (male jurists)–as with, say, the Syrian “muhaddith” (someone who recites Hadith), Umm al-Darda as-Sughra of Damascus. She was evidently known for commenting on fiqh (issues of jurisprudence); and is most renown for suggesting that women should be allowed to pray in the same seated position as men. (Hallelujah!) She supposedly tutored Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (would would become the fifth Umayyad caliph).

The fact that Umm al-Darda is now one of the more celebrated (Muslimah) champions for women’s rights (simply for this bold suggestion) shows us how low the bar has been set. That she is so often singled out as an exemplar tells us much of what we need to know about the prevalence of enfranchised women in early Islam.

Apocrypha from this period proliferate; so we must be cautious in according tribute. Another anecdote is about Amrah bint Abd al-Rahman–also a women known to have commented of fiqh. As the story goes, she once pleaded with a judge that an accused thief should not have his hand cut off, as the item he allegedly stole was worth less than a single dinar [gold coin]. As PIA would have it, we should therefore celebrate her as a stalwart of civil rights…as if Eleanor Roosevelt had magically appeared in the 7th century.

When it comes to female warriors in the Muslim world, a possible exception to the trend was a Khazraj woman from Medina referred to as “Rufaida al-Aslamiya”, who–the story goes–was a nurse for the Mohammedan forces. Her charge was to tend to wounded soldiers after battle–something women had been doing for thousands of years. She was not a scholar of medicine; she was merely a servant to “the cause”. {C}

Other female Sahabah are more incriminating of the Mohammedan record than exculpatory. Notably, Nusayba bint Ka’b al-Ansariyyah is famous for asking MoM why god only addresses men in the “Recitations” [i.e. the Koran]–a great question for which no answer was forthcoming.

In Mohammedan society, the exceptions proved the rule. During the two centuries after MoM’s death, there was a handful of Muslimahs who were employed by the caliphs as propagandists–such as Layla bint Abdullah al-Akhyaliyya (an Umayyad courtier from the Banu Amir); and, later, the so-called “Abbasid singing girls”. {C} However, such women were little more than apparatchiks. These members of the caliph’s court were analogues of what would soon thereafter be dubbed, “gungnyeo” in Korea: maidens employed by the imperium as writers of verse and composers of music (i.e. material produced sheerly as tribute to the ruler, for his own amusement). Their charge was to entertain, not to engage in scholarship or political activity.

Was such a vocation a sign of burgeoning female empowerment? Hardly. The job of such Muslimahs was crafting encomia to the powers that be (i.e. officially sanctioned panegyrics). Their material (which amounted to little more than an exercise in sycophancy) compares unfavorably to that of the great female writers elsewhere in the world at the time.

The list of exalted Muslimahs seems endless: Hafsa bint Ibn Sirin and Amrah bint Abd al-Rahman (7th-century Hijaz), Abida al-Madaniyya and her granddaughter, Abda bint Bishr (8th-century Andalusia), Nafisa bint al-Hasan ibn Ziyad (late 8th- / early 9th-century Egypt), Umm Umar al-Thaqafiyya (9th-century Baghdad), etc.

Concerning any one of them, we might ask: Was she allowed to be a leader? Was she given authority over any men in government? Was she HERSELF allowed to produce fiqh? The answer to all such questions: No. Though there is something to be said for being allowed to PARTICIPATE, the station in life of these women was primarily one of subordination. Their charge was simple: To serve the powers that be; not to be a pioneer (and CERTAINLY not to question authority or to challenge the established order). Free-thought played no role in the vocation of any of these Muslimahs.

One might ask: How common was literacy amongst women in Dar al-Islam? The evidence is sparse. From what we know, it can be adduced that it was rare, indeed, for women to be literate. Nevertheless, we are now treated to a smorgasbord of apocrypha about how esteemed women were in Dar al-Islam.

The tales seem endless: Ruqayyah bint Husayn ibn Ali [a.k.a. “Sukaynah”] was supportive of her fellow Ali’ds (late 7th century), Rabi’ah al-Adawiyya al-Qaysiyya of Basra was extremely pious (8th-century), a woman named “Arib” was a celebrated courtier in Baghdad (9th-century), and Karima bint Ahmad al-Marwaziyya of Marv / Khorasan (a.k.a. “Umm al-Karam”) commented on ahadith in Mecca (11th century). Such women are showered with accolades for dubious reasons. (I mention these Muslimahs because they are the only women Chase Robinson could think of to mention in his book, “Islamic Civilization in Thirty Lives”.) Whether the touted Muslimah was an Ali’d sycophant (Sukaynah), a Sufi ascetic (Rabia al-Adawiyya), a popular sex-slave / court-performer (Arib), or a hadith reciter (Umm al-Karam), none achieved anything of note. In no case did their renown indicate a reverence for women as equal citizens.

There’s more. We hear tales of female “muhaddith” [hadith reciters] like Umm Adhah al-Adawiyyah of Hijaz (7th century) and Zaynab bint Umar ibn al-Kindi of Baal-bek (late 12th / early 13th century). Each of them was, at best, a proselyte / missionary. These women were not pioneers; they were myrmidons. Mere clerical work is hardly a reason to extol anyone–male or female. Whenever we hear about exalted Muslimahs, they were invariably reciters of Hadith (a.k.a. “Hadith scholars” in the argot of PIA), unconcerned with scholarship in anything outside their narrowly-defined religious discipline. Relaying information (especially when merely about folklore) is not the same as adding to human knowledge.

Already mentioned were the two most notable women in the Muslim world: Lubna of Cordoba and Fatima of Madrid–pseudo-scholars from the late 10th century. (Other female Andalusians are probably apocryphal.) It is no coincidence that these last two anomalies occurred in Andalusia. Pace the cities of Baghdad in Mesopotamia and Damascus in Syria (for the same limited span of time, during Islam’s so-called “Golden Age”), that particular region (especially Toledo, Cordoba, and Granada) boasted by far the most liberal (read: pluralistic, intellectually vibrant) climate anywhere in the Muslim world–at any time between MoM’s ministry and the 20th century. Therefore, to attribute the scholarly achievements of ANYONE–male or female, at that particular time and place–to Mohammedanism is to confuse “because of” with “in spite of”. {D}

Cosmopolitanism emerged in isolated pockets for limited amounts of time when / where geo-political exigencies allowed it; daily muezzin calls had nothing to do with it. Suffice to say: The Koran was a sudden boon to women’s role in society in the same way that, say, Darwin’s “Origin of the Species” was a sudden boon to Creationism. From the female minds we’ve enumerated in this Endnote, a trend is hard not to notice; and it does not support PIA claims about feminism being subtly embedded in the Sunnah. {E}

The most telling exception to the overwhelming trend was a 17th-century Mughal princess named Ze[e]b un-Nisa, who allegedly TRIED to write some poetry (under the pen-name, “Makhfi”; meaning “The Hidden One”). It bears worth repeating: She was consequently imprisoned by the presiding Timurid Emperor, Aurangzeb (who also happened to be her own father) for the last couple decades of her life. Needless to say: This is not an example one would use to make the case that women’s roles were prized in the medieval Muslim world.

How many women wrote Hadith? None. How many women were fuqaha? None. How many women had a say in the codification of the Sunnah? None. To this day, there has never been a prominent female “alim” (i.e. an “alimah”), a female “mevlana”, or a female “mufassir”. {F}

That the ulema has been overtly patriarchal since its inception is unsurprising once we read the Koran: a book addressed exclusively to those who were intended to make all of society’s important decisions: men. {G} When in 1374, Giovanni Boccaccio published his “De Claris Mulieribus” [Concerning Famous Women], the project would have been inconceivable even in Dar al-Islam’s most progressive centers. (That includes Andalusia under the Almoravid dynasty during the 11th and 12th centuries as well as Bagdad prior to the Mongol seizure in 1258.)

Overwrought anecdotes of these devout Muslimahs seem to only highlight apologists’ desperation; as touting such figures is–to put it kindly–grasping at straws. The names go on and on. Samra bint Nuhayk al-Asadiyya supervised a souq in Mecca. Shaffa [alt. Ash-Shifa] bint Abdullah supervised a souq in Medina. In the late 15th / early 16th century, a mystic from Damascus named Aisha bint Yusuf al-Ba’uniyyah is said to have written some poetry. Shall we suppose that such eventualities had to do with anything the Koran said? Do we have ANY Islamic scripture to thank for such appointments? Could this have occurred SANS Sunnah?

Other accomplishments have merely to do with piety. Sayyidah Nafisa bint Hassan al-Anwar engaged in dawa. Sukayna bint Hussein [alt. “Sakina”] criticized the religiosity of the Umayyads. Sayyida Nafisa of Mecca was very, very, very devout. Fatima bint al-Hasan ibn Ali ibn al-Daqqaq al-Qushayri knew the isnad extremely well. A Hijazi woman named Umm al-Khayr Amat al-Khaliq commented on the Hadith. Etc. Etc. Etc. In some circles (wherein Islamic apologia thrives), each of these women is lauded as if she were the Muslim equivalent of Ada Lovelace. Alas, the most such icons seem to have done is memorize scripture and pray a lot.

Once we deem extreme religiosity to be a grand achievement, anything goes. {H}

It is important to note that most of the (ACTUAL) female luminaries listed above were highly-esteemed in their time; and most are revered to this day (by people all over the world). What of Muslimahs during the same period? The total number of women in the Muslim world who significantly influenced the way men thought / behaved: zero. Why zero? The Koran offers all the explanation that we need: women should know their place (which is below men).

There were sporadic cases of female writers in the Muslim world–as with the aforementioned 17th-century Mughal-Safavid princess, Ze[e]b un-Nissa. But here’s the thing: She was forced to clandestinely compose her poetry under the pen-name “Makhfi” [the hidden one]. Once exposed, she was imprisoned for her writing.

Let’s be clear on this point: Short of chalking this glaring dearth up to some inherent deficiency in the intellectual capacities of women in the Muslim world, we can only attribute it to environmental factors (i.e. to nurture rather than to nature). Muslimahs were not any less capable than women in the rest of the world; it was the ambient CULTURE that held them back.

That was all BEFORE the Enlightenment. It was only AFTER the Enlightenment (at the onset of the 20th century) that isolated iconoclasts–male and female–within the Muslim world finally started throwing off the shackles of antiquated dogmas.

While there were some prominent writers in the Muslim world during this period (i.e. the Middle Ages), when we survey the extolled “ulu al-ilm” (owners of the science), “ulu al-albab” (owners of the sharpness of mind), and “ulu al-abshar” (owners of the future views) throughout Muslim history, we find that there was almost never a prominent women amongst them.

Meanwhile, even the stridently patriarchal–nay, misogynistic–Roman Catholic Church allowed some room for a few female expositors. I don’t count many fabled Muslimahs simply because they were either apocryphal or–to the degree that they were historical–were not stalwarts of female empowerment.

So how shall we think of the Muslimahs we encounter in such overwrought Islamic historiography? At best, they might be compared to the slew of “trobairitz” (female Occitan troubadours) popular in Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries. Other comparisons include the French writer Catherine d’Amboise and the Scottish poetess, Aithbhreac Inghean Coirceadal (both of the 15th century). We might also compare such Muslimahs to European women of the 16th century like the Austrian-Jewish writer, Rachel Akerman; Italian writer, Isabella Andreini (a.k.a. “Isabella Da Padova”); Toulousaine poetess, Gabrielle de Coignard; French writer, Madeleine Des Roches; or the Italian courtesan, Veronica Franco (none of whom made the cut on the above list, for the same reasons).

Again: Muslimahs typically cited as poets by PIA were either officially sanctioned panegyrists (e.g. the 12th-century Persian, Mahsati Ganjavi), the wives / daughters of powerful men, or simply women who were known to have, well, written something down at some point (e.g. “Lady” Mihri Hatun; a poet in the Ottoman Empire during the late 15th century who has a few stanzas of surviving verse).

Court panegyrists are also not counted. We hear of Abbasid slave-girls like Inan bint Abd-ullah and Fadl al-Sha’irah of Yamama (as well as Arib al-Ma’muniyya) from the 9th century; but they were SLAVES, so hardly count as examples of female empowerment.

Other Muslimahs are the subject of local legend, such as Hausa (Nigerian) Queen Bakwa Turunku of Zazzau [alt. Nikatau; now Zaria]; and her daughter, warrior-queen, Amina Sukhera (a.k.a. “Aminatu”). Typically placed in the 16th century, their legends are based on actual queens–though much about them is likely apocryphal. More to the point, it is unclear exactly how Muslim they may or may not have been. The evidence is sparse. (The same goes for the fabled Indian warrior [“khatun”], “Chand Bibi” of Bijapur / Ahmednagar in the 16th century.)

These women are not so much historical figures as embellished characters inserted into Mohammedan lore. Apocryphal or not, their deeds are neither historically significant nor precedent-setting.

And what of writers / intellectuals? Outside of Fatima al-Fihri of Kairouan, there is not much to report. In the event that any woman DID manage to achieve something of note within the Muslim world, she was SECULAR–as with the Andalusian poets (listed above): Nazhun al-Garnatiya bint al-Qulai’iya, Hafsa bint al-Hajj ar-Rakuniyya, and Thoma. (And Thoma may very well have been apocryphal.) The Persian poetess, Mahsati Dabira of Ganja[vi] (also listed above) was hardly an exemplar of female empowerment in Dar al-Islam, as she was persecuted for her outspoken condemnation of religious dogmatism, puritanism, and obscurantism. So rather than making the case for Muslimah suffrage, she makes the opposite case.

We might note that “A Thousand And One Nights” was based on the Persian anthology, “Hazar Afsan”. Lest we forget, the narrator of these tales was a female: the fabled Persian story-teller, Scheherazade. This had nothing to do with the influence of Islam; it was a vestige of the lore’s Persian origins.

Hafsa bint Sirin al-Ansariyyah is another Muslimah known to have commented on fiqh during the era of the “Salaf” / “Tabi’een”. During the Middle Ages, a few other female names crop up in Islamic historiography. Fatima bint Abd al-Rahman (a.k.a. “al-Sufiyya”), Umm Isa bint Ibrahim, and Amah al-Wahid of Baghdad commented on fiqh during the 10th century (Shafa’i school); and have been retroactively dubbed “muftis” by some hagiographers. Thereafter, there are semi-credible accounts of:

- Thumal al-Qahraman, who worked as a clerk for a court (drafting responses to petitions) in the 10th century. It should be noted that she was not permitted to have a say in matters of sharia; as qadis could only be male.

- Fatima bint Muhammad ibn Ahmad of Samarkand, who commented on fiqh in the 12th century.

- Zaynab bint Makki ibn Ali of Damascus, who commented on fiqh in the 13th century.

- Zaynab bint Ahmad ibn Umar and Fatima bint Abbas of Damascus, who commented on fiqh in the 14th century.

These four women were essentially medieval paralegals. Yet to hear the perorations of some PIA, one would think the medieval Muslim world was flooded with a legion of Mary Elizabeth Wollstonecrafts. Such farce only seems plausible in an environment addled by dogmatism. To contend that such women were exemplars of universal enfranchisement, one is required to treat sycophants as trailblazers.

We also hear tales of the Ottoman poetess, “Lady” Mihri Hatun from the late 15th century, who was permitted to compose verse in the court of the very liberal sultan, Bayezid II. There are also dubious tales of the (Hanbali) Bedouin, Ghaliyya of the Wahhabis, who used magical powers during the war between the House of Saud and the Ottomans in the early 19th century. Treating these Muslimahs as icons of feminism is rather a stretch.

There were sporadic cases of female writers in the Muslim world–as with the 17th-century Mughal-Safavid princess, Zeb un-Nissa. But here’s the thing: She was forced to clandestinely compose her poetry under the pen-name “Makhfi” [the hidden one]. Once exposed, she was imprisoned for her writing. Court panegyrists are also not counted. We hear of Abbasid slave-girls like Inan bint Abd-ullah and Fadl al-Sha’irah of Yamama (as well as Arib al-Ma’muniyya) from the 9th century; but they were SLAVES, so hardly count as examples of female empowerment.

To reiterate: The most telling exception to the overwhelming trend (a paucity of female intellectuals in Dar al-Islam) was the 17th-century Mughal princess named Ze[e]b un-Nisa, who allegedly TRIED to write some poetry (under the pen-name, “Makhfi”; meaning “The Hidden One”). It bears worth repeating: She was consequently imprisoned by the presiding Timurid Emperor, Aurangzeb (who also happened to be her own father) for the last couple decades of her life. Needless to say: This is not an example one would use to make the case that women’s roles were prized in the medieval Muslim world.

When in 1374, Giovanni Boccaccio published his “De Claris Mulieribus” [Concerning Famous Women], the project would have been inconceivable even in Dar al-Islam’s most progressive centers.

Four other possible exceptions to the trend are worth noting:

- Sufi mystic, Rabia al-Adawiyya al-Qaysiyya of Basra [a.k.a. “Rabia Basri”] (late 8th century)

- Andalusian poetess, Hamda bint Ziyad of Granada (12th century)

- Sufi poetess, Aisha bint Yusuf al-Ba’uniyyah of Damascus–who’s (purported) poetry is now almost entirely lost (early 16th century)

- Kashmiri mystic, Habba Khatoon–known for her song, “Nightingale of Kashmir” (c. 1600)

These women were comparable to the legions of storied Christian nuns who composed specious religious tracts during the Middle Ages–none of whom I count either. Such figures do not warrant the kind of notoriety accorded to the female luminaries that have been enumerated in this essay. For their achievements were modest at best. {H}

Here the standards for qualification are consistent–and so apply irrespective of religious affiliation. I omit non-Muslim women for the same reason I omit the four Muslimahs above. We might ask, then: What of the non-Muslim counterparts to such Muslim women?

To illustrate that I am using such criteria consistently, let’s look at non-Muslims who fail to qualify as military figures. The bevy of European (Christian) mystics / theologians–men AND women–is not worth cataloging, as they do not qualify as luminaries either.

So let’s look at NON-Muslims who fail to qualify as “women of letters”; and fail to qualify for the same reasons. 27 notable examples of such European women:

- Byzantine consort and writer, Aelia Eudocia Augusta

- Greco-Roman (Georgian) missionary, Nino of Cappadocia

- Italian (Dominican) nun, Catarina di Giacomo di Benincasa of Siena

- Italian (Franciscan) nun, Chiara Offreduccio of Assisi

- French (Carthusian) mystic, Marguerite of Oingt [Beaujolais]

- French (Beguine / Dominican) mystic, Marguerite Porete of Valenciennes

- Swedish mystic, Birgitta Birgersdotter of Vadstena [Öster-göt-land] {I}

- Castilian (Cistercian) abbess, Sancha Garcia of Burgos

- Castilian (Carmelite) nun, Teresa of Avila

- Flemish (Cistercian) mystic, Beatrijs of Nazareth [Brabant] (a.k.a. “Beatrice of Nazareth”)

- Dutch mystic, Hadewijch of Antwerp [Brabant]

- Polish nun, Regina Protmann of Warsaw (founder of the Sisters of St. Catherine)

- Austrian (Beguine / Franciscan) mystic, Agnes Blannbekin

- Hungarian (Dominican) nun, Lea Raskay of Budapest

- German (Beguine / Dominican) mystic, Mechtild of Magdeburg [Saxony]

- German (Benedictine) abbess, Mechtild[is] of Edelstetten [Bavaria]

- German (Ottonian) abbess, Mathild[e] of Essen [Saxony]

- German (Ottonian) abbess, Sophia of Gandersheim [Essen; Saxony] {J}

- German (Benedictine) abbess, Gertrude of Hackeborn [Helfta; Saxony] {K}

- German (Benedictine) mystic, Gertrude of Helfta [Saxony; originally from Thuringia] (a.k.a. “Gertrude the Great”) {K}

- German (Dominican) nun, Christina Ebner of Nuremberg [Bavaria]

- Anglo-Saxon abbess, Herrad of Hoehenbourg / Landsberg [Alsace]

- Anglo-Saxon abbess, Hilda of Whitby [Yorkshire]

- Anglo-Saxon missionary, Walpurga of Devonshire (alt. “Valderburg”)

- Mercian abbess, Frithuswith of Oxfordshire (alt. “Frideswide”)

- East Anglian abbess, Withburga of Dereham [Norfolk]

- East Anglian anchoress, Julian of Norwich [Norfolk]

…none of whom made the cut in the survey. Bear in mind that such women achieved their (sometimes dubious) notoriety within the (misogynistic) climate of the (obdurately patriarchal) Roman Catholic Church. Medieval European Christendom was no panacea for female empowerment; so the bar here is quite low if we are to count every women who happened to earn clout within the system–as if isolated instances of localized prominence were an indication of burgeoning feminism.

Bear in mind that, in medieval times, the dominion of the Roman Catholic Church was grotesquely patriarchal–arguably the most patriarchal realm in human history. Even in these suffocatingly misogynistic environs, some women–obliged as they were to operate within such a suffocating system–sometimes managed to become the heads of small ecclesiastical operations. Their station was invariably assigned to them by a male-run establishment. They were allowed to conduct their affairs…so long as they knew their place in the grander patriarchal scheme. As writers, they were allowed to write only insofar as it was in the service of the church.

Such women did not make the cut (even as they were allowed to run their own local operations) for the same reasons I do not count Muslimahs who were renown for their bountiful piety (and were thus allowed to teach scripture). Excelling in evangelism is not a qualification in the present survey.

Alas, sometimes women in Christendom were celebrated merely because they toed the line–as with canonized women from the 3rd century:

- Agatha of Sicily

- Barbara of Nicomedia

- Lucia of Syracuse

Ergo piety as the basis for exaltation. This is the opposite of why women–or ANYONE, for that matter–should be revered.

And so when I omit those like Aisha bint Yusuf al-Ba’uniyyah, I do so for the same reasons I omit the women in this Endnote. As I show here, there were many women like her in Christendom; but that is NOT what we are addressing in this survey.

We might also note iconic martyrs like Georgian Queen Ketevan of Kakheti and the Georgian / Armenian saint, Shushanik.

Again: The criteria used in the present survey are the same between Muslim and non-Muslim women. In cataloging female luminaries, religious affiliation is moot. Storied Muslimahs who are often touted in Islamic apologia are disregarded for the same reasons I disregard such non-Muslim female writers found in the historical record. Sycophancy warrants no reverence.

At the risk of belaboring the point, here are a few other female authors who fail to qualify as “luminaries” in the pre-modern non-Muslim world:

- English writer, Margaret Roper; as well as the three Seymour sisters

- German writer, Katharina Schütz Zell

- French writer, Claude de Bectoz

- Swiss writer, Marie Dentière

- Italian writer, Margarita Bobba

- Japanese writers, Sei [no Kiyo-hara] “Shonagon” and Rikei no Katsunuma Nobutomo

Another example of middling notoriety is Northumbrian Queen Æthelthryth of Ely / Fenland [a.k.a. “Audrey”], who recorded some of her musings on paper–hardly an indication of a feminist awakening.

It should be clear, then, that I am consistent in applying criteria for the consideration of female luminaries–a qualification that applies irrespective of religion / culture / race.

It should be noted that pre-Mohammedan Arabian society was, in part, matrilineal in nature. While it certainly had its fair share of problems, it was a culture where women–especially mothers–were generally valued. In this respect, the only problem that the Koran / Sunnah solved was that of female infanticide–which seems to have sporadically occurred throughout the world in ancient times.

The case can even be made that Mohammedism made things WORSE for women, as it inaugurated a palpably PATRIARCHAL society in a region where matriarchy had previously been prevalent. For example, in the pre-Mohammedan Hijaz, children often lived with their mother and adopted their mother’s name (or the designation of the mother’s clan). Pursuant to the institution of the Sunnah, such a practice ceased.

In a nutshell: Prior to Islam, Bedouin culture was a mixed bag; after Islam, it was overtly patriarchal. That is to say: After MoM’s ministry, the subjugation of women only INCREASED.

In any case, the suggestion that women’s rights advocates–Muslim or non-Muslim–today should somehow base their cause on the Sunnah is nothing short of preposterous–a fact that becomes crystal clear upon simply reading the contents of the Koran. {B}

That anything based on the Koran / Hadith might be good for women is a fairy-tale. It should not be controversial to point this out; nor should it be problematic for Progressive Muslims to openly acknowledge this (incontrovertible) fact.

To conclude: It is no mystery why sharia–in ANY of its variegated forms–did not figure into the U.N. Commission On The Status Of Women when it was convened in 1946. Two years later, when the U.N. drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the document did not resemble anything found in Islam’s holy book. At all.

Nobody was surprised by this.

{A How is it that Khadijah came to be revered? Her renown as an accomplished businesswoman occurred before she’d ever met MoM; so we can’t attribute her success as a merchant to the Sunnah. (She is proof that the Sunnah did nothing to further empower women, as her thriving business is testament to the fact that women owned / operated their own enterprises PRIOR TO MoM’s ministry.) Khadijah was not alone. In 5th-century Yathrib, Salma bint Amr of the Banu Khazraj operated a successful enterprise–illustrating that in pre-Islamic Arabia, females could own and manage their own businesses. Tellingly, Khadijah has no notable accomplishment AFTER her betrothal to MoM other than encouraging him to propound his “revelations”; then supporting his ministry during its earliest years. We hear nothing of any endeavor to help OTHER women become independent business-owners. It seems that after becoming MoM’s wife, Khadijah had other priorities. For more on this matter, Appendix 2 in The Long History Of Legal Codes.}

{B If MoM had ever said something like, “Under no circumstances is it right to rape / beat a woman; no matter who she might be”, such a statement was omitted from the Hadith. In fact, such an admonition is countermanded by virtually everything else MoM actually did and said.}

{C We hear similar accounts of several other women, such as Layla al-Ghifaria and Suffiyah bint Abdul Muttalib.}

{D How many renown scholars–male or female–hailed from Medina and Mecca before the 20th century? Nil. The occasional iconoclast could not attribute her achievements to augmented piety…or to more strictly hewing to the Sunnah…or to more stringently following the directives in scripture.}

{E To review: Of the over TWO HUNDRED aforementioned female thinkers who lived during or in the millennium after MoM’s lifetime, only TWO were Muslim (while one–allegedly–later became Muslim).}

{F I should qualify this assertion. Coming up on the 14-century anniversary of MoM’s ministry, there have recently been some aspiring candidates (notably, in Indonesia). Ironically, such aspiration has not been abetted by appeals to the Sunnah; it is justified on categorically secular grounds (i.e. by appeal to fundamentally democratic principles). To attribute such headway to religiosity is to misread HOW and WHY these women accomplished what they did.}

{G Even when addressed to “you who believe”, it is clear that the Koran is referring to you MEN who believe (i.e. those who are expected to evangelize and fight). Even when referring to “nas” [mankind], humanity is conceived as a body represented by MEN (i.e. those making the decisions).}

{H In this brief catalogue of Muslimahs, I do not count Sufi mystics. Why not? For the same reason I would not accord esteem to any other mystic–male or female, Muslim or non-Muslim–at any point in history. Mystics are not thinkers. The paucity of prominent women of letters in the Ummah persisted through the emergence of renown 19th-century writer, Aisha Ismat bint Isma’il Taymur.}

{I She had such noted followers as (Swedish abbesses of Vadstena) Christina Hansadotter Brask, Anna Fickesdotter Bülow, and Margareta Clausdotter.}

{J Sophia was known as a king-maker, and was arguably more powerful in Europe than any woman had ever been anywhere in the Muslim world prior to the post-War period. Again: I did not count her in the main survey, as she does not meet the standards I set. Any accusations that I discount Muslimahs in the survey must make the case that they would qualify more than she.}

{K The two storied Gertrudes from the 13th-century mustn’t be confused. Both were Thuringian, and both plied their trade at Helfta in Saxony. The first Gertrude was an abbess. Gertrude the Great was a prolific writer in the abbey.}