The History Of Salafism I

May 5, 2020 Category: History

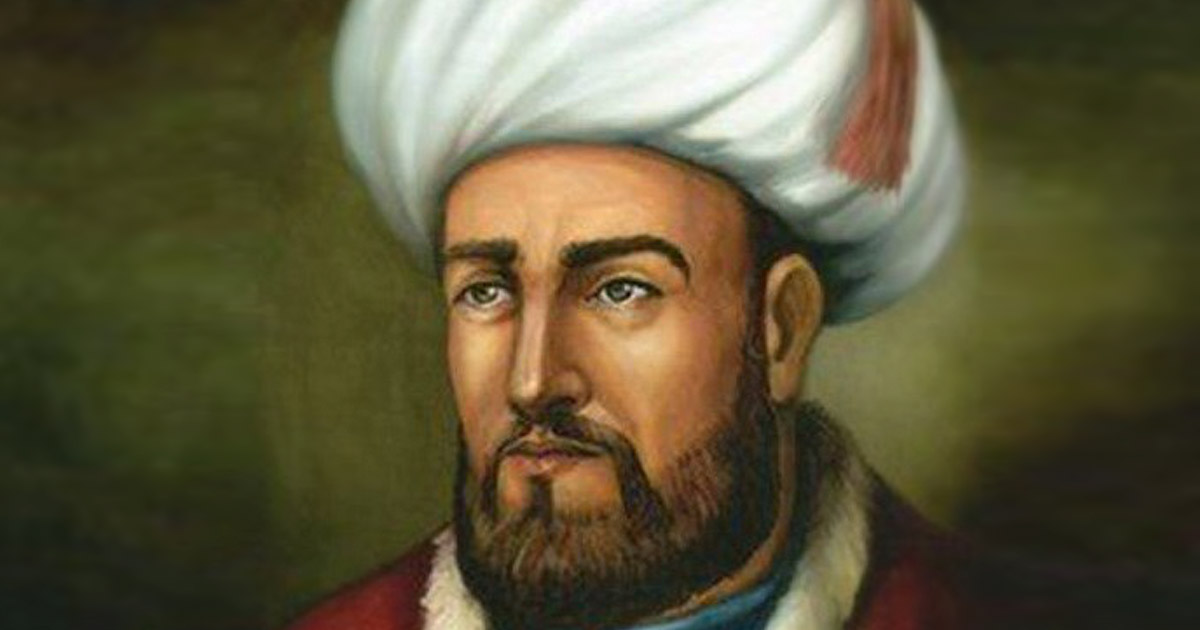

Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali is one of the most iconic Islamic fundamentalists in history; though–as we’ve seen–he was not the first to peddle a puritanical version of the Faith. But though he was not the first, he was one of the most–if not THE most–influential. He was, after all, highly skilled in the art of persuasion–an art in which any adept con-man excels. Consequently, he held tremendous sway across Dar al-Islam.

Doctrinal to his core, Al-Ghazali was hardly an innovative thinker. As with any proselytizer, his primary vocation was “balaghah” [rhetoric]. In other words: He was a sophist more than anything else. (To this day, the Islamic tradition of sophistry is referred to as “Rad al-Shubuhat”.) Being an ardent evangelist, Al-Ghazali was looking to bolster his rhetorical skills rather than to glean wisdom (in roughly the same way his contemporary, Christian theologian Peter Abelard had c. 1100 when HE devoted time to the Athenian expositors of the Axial Age.) Edification had nothing to do with it. {12}

Al-Ghazali fashioned himself a “mu-ta-kalim” [theologian] after his ultra-reactionary mentor, Al-Juwayni (an Ash’ari theologian who had carried out the legacy of Abu Said Hasan al-Sirafi). Consequently, he worked diligently to procure skills of persuasion so as to better carry out his charge; and to buoy his celebrity.

So what of this moniker, “mu-ta-kalim”? It is based on the phrase “ilm al-kalam”–commonly (and misleadingly) translated as “science of discourse”. {13} For Islamic apologists who advocate for this practice, though, the phrase is more accurately translated as “knowledge of theology”. Though even this is not precise, as “ilm” connotes something slightly different than genuine knowledge; as it pertains to a familiarity with–and embrace of–the Sunnah.

For many who touted it, “ilm al-kalam” was primarily concerned with RHETORIC (in the service of religious apologia). Only sometimes did it obliquely refer to a general incorporation of Greek philosophy into theological musings. For those who PRETENDED to value “ilm” (so-called), “ilm al-kalam” referred to the craft of pedantic rationalization. It was not a matter of erudition so much as it was procuring prodigious acumen in sophistry. (I explore the use of the buzz-term “ilm” at length in the Appendix.)

If we are to understand Al-Ghazali, it is important to recognize that he was a sophist as much as he was a religious revivalist. Yes, he read Greek texts (mostly Aristotle). However, he did so not to learn about the world, but to refine his craft–to procure a prodigious savvy in the métier of shrewd argumentation.

He employed euphuistic rhetorical tactics in service to fundamentalist Islamic apologetics; procuring a litany of platitudes that have ended up being profoundly influential to the present day. His interest in Aristotle was solely about enhancing his sermonic acumen. He was not excavating the Axial Age for erudition; he was poaching it for rhetorical ammunition. {17}

Bottom line: Almost all Salafi boilerplate can be traced back to Al-Ghazali’s derisive pontifications. {18}

To reiterate: Al-Ghazali was not engaging in anything that could be accurately characterized as critical inquiry; for his conclusions were foregone. The promulgation of (Shafi’i) ideological purity was his summum bonum. Having “ilm al-kalam” meant having the skills to effectively defend sanctified dogmas from detractors. While tremendously useful for the religious apologist, such a craft has nothing whatsoever to do with either knowledge OR science. {14}

Thus Al-Ghazali codified “fide-ism”: the theological position that pits Faith against Reason, prizing the former over the latter. The idea, then, was that critical thinking not only sews discord in Dar al-Islam (a practical concern), it is blasphemous (a theological concern).

We might also note Al-Ghazali’s unabashed misogyny–as when he declared: “The position of leader [imam] could never be given to a woman even if she possessed all the qualities of perfection and self-reliance. For how could a woman take the position of leader when she did not have the right to be a judge or a witness under most of the historical governments?” Good question.

After all, the Koran AND Hadith were overtly misogynistic in their worldview. {36} Even so, in making this (obnoxious) statement, Al-Ghazali was broadcasting his ignorance. Evidently, he was oblivious to the dozens of prominent female leaders that had arisen around the world for the previous two millennia (see part I of “The Empowerment Of Women In History”).

In many ways, Al-Ghazali was the analogue of the Roman Catholic zealot, Augustine of Hippo–who was just as contemptuous of critical / free inquiry (and of women). In this scheme, intellectual curiosity (under the aegis of “ijtihad”) was seen as heretical. (Augustine was a vehemently ant-intellectual expositor who believed in the salvation of HENS. As with Al-Ghazali, he reveled in the intoxication of his own dogmatic quagmire.)

Al-Ghazali concocted his own (demented) version of virtue-based ethics; but unlike Aristotle, he was merely using rhetorical tricks to rationalize foregone conclusions. His sole concern was to uphold the prized tenets (“aqidah”) of his favored version of Islam: Salafism.

Speaking of “virtue ethics”, it might be noted that the Classical Arabic term for “virtue” (“sawab”) can also be translated as “piety”. This semantic quirk is revealing, as it means these two things are often conflated–or even seen as synonymous–in Islamic discourse. (The nominal term for piety in Classical Arabic is “taqwa”, which carries with it the connotation: god-fearing; thereby inferring that piety is based in fear.) Hence what is often translated as “virtue” has almost nothing to do with what is normally understood as virtue. Rather it intimates that one is hewing to the designated “aqidah” [also translated as “creed”]; and thereby maintaining one’s “iman” [Faith]. Such “virtue” as obeisance goes against virtually everything Aristotle said.

This queer taxonomy is corroborated by the fact that LACK OF “ilm” is equated with IMPIETY via the term, “jahiliyya” (effectively, lack of awareness of the Sunnah). Thus “ignorance” is synonymous with failure to SUBMIT–a rather cockamamie epistemic standard.

Al-Ghazali’s material was no “Nicomachean Ethics”; it was an exercise in hyper-dogmatism. In his ardor to propound religious doctrine, his commentary did nothing to inform people about universal moral principles. The fact that he invoked Greek thought only made him more dangerous; as–for many–it made him seem erudite. {26}

Al-Ghazali and his ilk represented the antithesis of the figures who would later facilitate the Enlightenment. Unfortunately, he ended up having massive influence in determining Islamic orthodoxy. If the blame for Dar al-Islam’s intellectual bankruptcy can be placed at the foot of any one figure, Al-Ghazali is surely it. The extent of his (deleterious) influence cannot be over-emphasized. Indeed, Islam AS IT ACTUALLY CAME TO EXIST for most Muslims can be attributed to his odious legacy.

The point can’t be emphasized enough: As with Peter Abelard (who attempted to poach Classical Greek thought for his own religious purposes), Al-Ghazali’s only interest in Greek philosophy lay in serving his (atavistic) ideological agenda. And as with any theologian, he was only concerned with finding florid ways to rationalize pre-established tenets. In the event that he was unable to find a compelling rationalization for some point of doctrine, he would simply make things up–as when he put an expiration date on one’s chance to convert to Islam. (!) What might that have been? 40 years old (after which a non-Muslim was doomed to hellfire, regardless of penance). {15}

To reiterate: Al-Ghazali was the quintessential dogmatist. For him, critical inquiry was nothing short of blasphemous. Free-thought constituted “bid’ah” (that dreaded hobgoblin: innovation); and so was to be deemed haram. As far as he was concerned, piety (subservience), not intellectual curiosity, was the prime directive for mankind. Anything else was tantamount to heresy. It is thanks to Al-Ghazali’s precedent that evangelism (typically conducted under the aegis of “dawah”) remains a cottage industry (known as as “da’i”) to the present day. (I elaborate upon this point in Postscript 2.)

The puritanical mindset of the “Khawarij”, which had been on the wane, was re-invigorated in the wake of Al-Ghazali’s frenetic proselytization. {16} It should be clear, then, that Al-Ghazali was not a Reformer; he was a REVIVALIST. This was made plain by the title of one of his most popular works: the “Hya Ulum ad-Din” [alt. “Ihya’u Ulumiddin”; “Revival of Religious Way of Life”]. The tract was later re-titled “Kimiya-yi Sa’adat” [Alchemy of Happiness] for propagandistic purposes. Its main themes were salvation, damnation, and religious duties. To say that it contributed NOTHING to human understanding would be charitable. To say that it hamstrung all worthwhile discourse throughout the Muslim world for centuries would be an understatement.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Al-Ghazali was a self-proclaimed “mu-jaddid” (one who renews the Faith). In other words: he was–more than anything else–a religious revivalist. This is simply to say that he sought to BRING BACK that which had PREVIOUSLY BEEN. He succeeded in this task to a degree he could not have imagined.

Equipped with a finely-honed rhetorical acumen gleaned from Aristotle’s commentary, Al-Ghazali’s preachments ended up being influential throughout the Ummah thereafter. Rather than just a flash in the pan, he was the spark that ignited the conflagration that would eventually burgeon into Salafism as we know it today.

It is worth noting the stark contrast between Al-Ghazali (doyen of doctrinal obduracy) and estimable Muslim luminaries like Avicenna (a 10th century Progressive thinker from northeastern Persia) and Averroës (an 11th-century Progressive thinker from Andalusia). Al-Ghazali–the most celebrated commentator of the age–could be accurately characterized as the anti-pole of Avicenna and Averroës. He was, after all, the quintessential revivalist. That is to say, he was an adversary of Progress.

The so-called “Golden Age” of Islam was not as peachy-keen as some Islamic apologists often make it out to be (as I show in my essay, “Islam’s Pyrite Age”). Though Andalusia was a COMPARABLY Progressive region during the Middle Ages, it was not nearly as cosmopolitan as would sometimes seem from some of the romanticized portrayals that have become so popular.

Take 11th-century Granada. When a Jewish man (Joseph ben Samuel “ha-Nagid”) was appointed to the position of vizier by the local potentate (Badis al-Muzaffar) c. 1066, a mob of indignant Muslims stormed the palace, then lynched and crucified him. The mob then proceeded to massacre thousands of the city’s Jews. Why did they react in this manner? Per sharia, “dhimmis” are not supposed to have a position of authority over Muslims…EVER…under any circumstances. So the political appointment was seen as an outrage.

Bear in mind: This uprising occurred in one of the most liberal places in the Muslim world…during what is reputed to be its most cosmopolitan era. Medieval Andalusia was, in fact, not the utopia of pluralism some historiographers make it out to be. Christians were left to their own devices so long as they kept their heads down. Thus: Even during Dar al-Islam’s most progressive epoch, strict versions of “sharia” was seen as incontrovertible, and non-negotiable. By medieval standards (a very low bar to clear), Granada was somewhat cosmopolitan (that is: quasi-liberal). Yet according to the timeless standards of civil society, it was still palpably illiberal. It is for this reason that Islam’s “Golden Age” is more accurately described as its “Pyrite Age”.

So Al-Ghazali was hardly the ORIGIN of Islamic fundamentalism. Even if it could be shown that he was concocting this fundamentalist theological worldview from whole-cloth, we would be forced to revise the definition of “recent” to “within the past millennium” should we deign to uphold the (spurious) claim that fundamentalism is a (relatively) “recent” development in Dar al-Islam.

Al-Ghazali’s role in the history of Islam is crucial to grasp. He galvanized what was a faltering Islamic fundamentalism, thereby revitalizing the Salafi tradition that he felt was in danger of being lost. And so Islamic apologists today rhapsodize about Al-Ghazali as if he instigated the equivalent of the Copernican Revolution. At the end of the day, though, he was a revivalist, not a revolutionary. (For more on this point, see Eric Ormsby’s “Ghazali: The Revival of Islam”.)

Al-Ghazali’s perorations were such a resounding success, even some of the more naive of ostensibly-Progressive Islamic apologists have been known to celebrate him, and selectively quote him. {20} Islamic apologists often tout the fact that Al-Ghazali “studied” the philosophers of ancient Antiquity. What they neglect to mention is that this “studying” was merely a matter of cultivating his ability to debate. To recapitulate: He sought to sharpen his discursive dexterity in order to better undertake “dawa”, not to discover noble tasks to which said dexterity might be put; NOR to cultivate a thorough understanding of the natural world. All was according to god’s will: THAT was the explanation to EVERYTHING. It’s all anyone ever needed to know. Period.

And so it went that Al-Ghazali’s most popular work was entitled “Ihya Ulum al-Din” [Revival of the Principles of the (Islamic) Way of Life]. The massive corpus consisted of dozens of volumes. It was effectively a re-articulation of the Mohammedan catechism; with extensive commentary and elaboration. In other words: It was the opposite of a clarion-call for reform.

The polemic of Al-Ghazali expresses nothing but contempt for heterodoxy, derided as “bid’ah” (innovation). He was charged by his employer (Seljuk vizier, Nizam al-Mulk) to provide a rationalization for an Islamic theocracy. {16} His job was to furnish Islamic rulers with REASONS WHY those who were designated as “zindiq” by the regime [meaning “heretics”; derived from the Parsik term, “zandik”] were, indeed, heretical. Al-Ghazali was an avid careerist; and being employed as a State propagandist was a surefire way to secure fame. As a hired apparatchik, he wasted no time currying favor with those in power. (This is not to say he was a “sell-out”; it is quite likely that he genuinely believed everything he said.)

One might wonder, then: After all this “study”, what phenomenal rhetorical skills did Al-Ghazali end up procuring? His most famous syllogism is the following: “If the world had two gods, it would surely go to ruin. The world has not gone to ruin. Therefore there can’t be two gods.” (After all his brushing up, THAT was the best he could manage.)

There are various indications of Al-Ghazali’s dogmatic cast. One of his doctrinal sticking points was his insistence that resurrection on Judgement Day involved a literal (corporeal) rising from the dead. For a literalist like Al-Ghazali, nothing was to ever be taken metaphorically. (Fundamentalists are incapable of analogical thinking.)

We needn’t quibble over the pointless issue of whether or not Al-Ghazali was Sufi; and, if so, when and how and to what extent. Insofar as it could be said that–following his brother–he dabbled in one or another version of mysticism later in life (and thus tangentially affiliated himself with Sufism), he might possibly be considered Sufi-adjacent in certain respects. Even if we grant that he was in some (highly circumscribed) way inspired by some aspects of Sufism, he was still a de facto Salafist. Religious fundamentalism is religious fundamentalism, regardless of the branding. {21} I explore this point further in Postscript 2.

Al-Ghazali’s aversion to (genuine) knowledge was made evident in his attitude toward any learning done outside the bounds of strict theological study (that is: beyond the pursuit of maximal piety). With an unabashed contempt for scholars, he said: “Though you studied a hundred years and assembled a thousand books, you would not be prepared for the mercy of god except by pious works.” Elsewhere, he stated that men “should be forbidden as much as possible the perusal of philosophical writings.”

Al-Ghazali admonished people against disputation (ironically: the very thing to which he himself had devoted his life). In other words: “It’s fine when I do it; but nobody else should.” Another quote commonly attributed to him tells us everything we need to know about his agenda: “Do not dispute any matter with anyone; for much harm lies in argumentation; and its evil is greater than its benefit.” (Such hypocrisy is typical of the proselyte. The catch, though, is that the “don’t question, just accept” approach works well for oneself only when EVERYONE ELSE abides by it.) In other words: Al-Ghazali was the consummate Salafist.

Al-Ghazali is also known for saying: “The real friend is the one who, when you ask him to follow you, doesn’t ask where; but gets up and goes.” On the face of it, this abjuration sounds laudable: unconditional loyalty. But what’s really going on here? Al-Ghazali did not want people questioning the tenets he laid out, as doing so might cause dissent…thereby precipitating factionalism. So, in the hypothetical scenario, HE represented the “real friend”; and the lesson was simply: Don’t question, just follow. (Considering Koranic passages like 3:28/118, 5:51-57/80, 6:13, 9:23, 48:29, and 60:1-13 admonish Muslims not to befriend non-Muslims, the implication of “real friend” here was well-understood.)

The concern here is disrupting the established order. To make this point clear, Al-Ghazali declared: “If those who don’t have ‘ilm’ avoid scholarly discussions, then dissension will end.” (Translation: If you’re not with the program, then keep your mouth shut. Don’t get out of line. Keep your head down and so as you’re told. Otherwise, there will be problems.) What did he mean by “ilm” here? We don’t have to wonder; for he tells us explicitly: “The essence of ‘ilm’ is to know what obedience and worship [‘ibadaat’] are.”

So to translate his use of “ilm” as “knowledge” is egregiously disingenuous. If anything, Al-Ghazali meant by “ilm” something resembling supplication. PIETY was the hallmark of “ilm” (as I discuss in the Appendix). As far as he was concerned, orthodoxy took precedence over free inquiry (see Postscript 2).

One must assume that Al-Ghazali realized that if people were allowed to explore secular thought, their Faith might be shaken. He was surely aware that the dogmas he promulgated would not be able to withstand robust critical inquiry. (Free inquiry is the bugbear of institutionalized dogmatism.) It should come as no surprise, then, that he sternly discouraged people from engaging in critical inquiry: “The hypocrite looks for faults; the believer looks for excuses,” as he famously put it. The lesson: If you seek to find faults with the prescribed doctrine, you are a hypocrite (i.e. a heretic).

There’s that obsession with “takfir” again! According to this thinking, REAL Muslims only concern themselves with finding excuses for doing whatever they’ve been instructed to do. This is the epitome of the Reactionary mindset; and the hallmark of Salafism to the present day. {14}

Being vehemently anti-intellectual, Al-Ghazali was especially contemptuous of philosophy. So it should come as no surprise that his magnum opus was entitled the “Tahafut al-Falasifa” [Incoherence of the Philosophers]. In this treatise, he reserved special disdain for Avicenna and Averroës (to repeat: the quintessential representatives of Islamic Reform).

Over the course of this tendentious screed, Al-Ghazali was unabashed in his seething contempt for the pursuit of ACTUAL knowledge about the world (then known as “natural philosophy”). He wrote that the laws of nature were a devious fiction; as the very notion contravened the idea that at any given moment, it is god’s will [“hukm”] that determines what happens. Far be it from us to question WHY anything might happen. In other words, the very concept of SCIENCE ITSELF was deemed subversive.

All is explained by the provisions of the Abrahamic deity [“ahkam”]–that is: by god’s will. End of discussion.

To the very limited extent that Al-Ghazali allowed for SOME tid-bits of scientific insight here and there, it was ONLY insofar as it served his theological agenda. Thus certain scientific claims were permitted IF they could be made to comport with his own catalogue of sacrosanct dogmas.

It is no coincidence that, pursuant to Al-Ghazali’s highly-influential proselytization, the so-called “Golden Age” of Islam quickly came to an end. Though no particular person can be said to have single-handedly precipitated the demise of this (soon-to-be-doomed) epoch of open-inquiry, the mindset Al-Ghazali promulgated certainly took its toll. The irony is that resurrecting the creed of the Salaf is what led to the dissolution of Islam’s “Golden Age”.

The famed Andalusian polymath (and consummate freethinker), Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushid of Cordoba (a.k.a. “Averroës”) soon wrote an indictment of Al-Ghazali’s mendacious “Incoherence of the Philosophers”…sardonically entitled, “The Incoherence of Incoherence” [“Al-Tahafut al-Tahafut”]. Presumably, Averroës opted for this title because “Al-Ghazali Is A Bumbling Idiot” would have not been nearly as clever. {4}

Note that Averroës was not the only scholar to take exception to Al-Ghazali’s screed. Another Andalusian polymath (Abu Bakr ibn Tufayl of Granada) penned a scathing riposte as well: “Philosophus Autodidactus”. In it, Ibn Tufayl countered Al-Ghazali by championing “ijtihad” (independent thought; Reason)…though the term would later be contorted by perfidious actors into meaning quite the contrary. {5}

To recapitulate: Al-Ghazali’s disdain for critical inquiry (nay, for philosophy in general) was especially directed at metaphysics, which naggingly trespassed on his coveted theological musings. Presumably, he did not have any qualms with (what he saw as) “science”. After all, he’d not yet gotten the memo that the Earth was spherical (that is, not–as the Koran states–flat). Typical of the senescent cartography of the Dark Ages were maps where the “known world” had edges: often seen as the LITERAL edges of the world. The authors of the Koran clearly thought the world was flat. (Not a single passage in the book indicates that the author’s might have suspected the Earth was a spherical body floating through space.)

So far as Al-Ghazali saw it, the Koran WAS “science”; and all “science” could ever be was heeding whatever the Koran stated. And that’s all there was to it.

As with most theologians, Al-Ghazali fancied himself a friend of “mantiq” [logic]…so long as it served his dogmatic purposes. (What he called “mantiq” was little other than INSTRUMENTAL reasoning–the most promiscuous of didactic utilities.) Revealingly, he referred to logic as “fan” [i.e. an “ART”]. For, as far as he was concerned, the solution to those pesky metaphysical abstractions was to further indulge in the dogmatism-of-choice, employing whatever suite of rationalizations he could cobble together. He did not want to have to think for himself; and he didn’t want anyone else to think for themselves either. (If HE wasn’t going to do it; then to hell with anyone who tried.) It is no surprise, then, that Al-Ghazali despised Neo-Platonism so virulently.

So the contrast is stark: Averroës was a scholar who prized critical reflection; Al-Ghazali was a hyper-dogmatist for whom critical reflection was sacrilegious. Like any other fanatical theologian, Al-Ghazali was threatened by knowledge ITSELF…even as his pedagogical adversary, Averroës, openly recognized all that secular insights could offer.

In sum: Al-Ghazali’s ultimate nemesis was not superstition or human suffering or social injustice; it was free inquiry. More to the point: His greatest fear was the heterogeneity amongst the hoi polloi that might be precipitated by such unbridled inquiry. Heterodoxy was, for him, the ultimate nemesis of piety. Homogeneity of thought, he contended, was therefore imperative.

We should not be entirely shocked to find that no major Enlightenment philosopher lists Al-Ghazali as an influence. {6} Contrast this with Averroës, who was profoundly influential in the Enlightenment movement (in spite of the fact that he was Muslim, not because of it). Had it had been up to Averroës (or Avicenna, for that matter), the Muslim world may have undergone an Enlightenment as well. Unfortunately, in most of the Ummah, it was the thinking of Al-Ghazali and his ilk that prevailed. This tragic legacy is evident in the abiding Reactionary mindset we witness to this day throughout much of Dar al-Islam. {6}

More than his unabashed scorn for philosophy, Al-Ghazali abhorred mathematics. This can be held in contradistinction to the celebrated Persian polymath, Mohammad ibn Musa of Khwarezm (a.k.a. “Al-Khwarizmi”): lover of algorithms and a pioneer in algebra. Indeed, Al-Ghazali wrote that the manipulation of numbers–nay, the entire enterprise of mathematics–was the work of the devil. (Gadzooks!) Al-Ghazali’s rantings served as a touchstone for subsequent Salafi ideology…where any intellectual activity devoted to concerns beyond the Sunnah was disdained.

It is no coincidence that, thereafter, intellectual activity evaporated in the Muslim world.

The juxtaposition here is illustrative of the present thesis. It is important to bear in mind that Averroës and Al-Ghazali, though anti-poles intellectually, were BOTH MUSLIM. Consequently, it is incumbent upon us TODAY to ascertain what, exactly, made the former estimable and what, exactly, made the latter degenerate. Such discernment–so vital to understanding history–is untenable within a Reactionary mindset, wherein puritanical thinking narrowly constrains the parameters of mental activity. Only by assessing things according to a new paradigm can such fundamental distinctions be accurately explained.

Insofar as we remain hostage to the contents of the scriptures in question, it will be impossible to bring modern insights to bear on ancient dogmas; or to re-asses the credence of institutionalized dogmatic system. The sham that is “received wisdom” depends on this. Dogmatism–epitomized by Al-Ghazali–enables it.

Pursuant to Al-Ghazali’s grandiloquent asseverations, Muslims were encouraged to spurn the Ummah’s greatest thinkers: Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Al-Biruni, Azophi, Avicenna, Averroës, et. al. Such luminaries were all declared heretics, and their books burned. It is likely due to Al-Ghazali’s censorious agenda that we no longer have the works of the great freethinker, Ibn al-Rawandi of Khorasan (from the 9th century).

In a twist of irony verging on the Kafka-esque, the work of said heterodox Muslim thinkers was thereafter embraced by EUROPEAN intellectuals; which, in turn, helped to spur the Renaissance–and subsequent Enlightenment–in the Occident. The ingrained antipathy–nay, hostility–toward the natural sciences (and to innovative thinking in general) sealed the fate of Dar al-Islam…even as Europe awoke from the long religious delirium of the Dark Ages.

While Enlightenment thinkers emerged from the dogmatic quagmire in which Christendom has been plunged, Dar al-Islam immersed itself deeper within its own dogmatic quagmire. In hindsight, it became plain to see how it was that the Occident slipped into such intellectual blight in the first place. As the 10th-century Arab historian, Al-Masudi aptly put it (when explaining how the European Dark Ages began): “Ancient Greeks and Romans had allowed the sciences to flourish. Then they adopted Christianity. In doing so, they effaced the signs of learning, eliminated its traces, and destroyed its paths of inquiry.” Science was eclipsed by institutionalized dogmatism. Little did Al-Masudi know, the same thing would happen to Dar al-Islam; and for analogous reasons. (!)

Dogmatism doesn’t like mirrors. It’s something EVERYONE ELSE is doing. (When WE do it, it’s simply called “Faith”.)

As if it weren’t already bad enough, Al-Ghazali’s writings encouraged martyrdom. “Are you ready to cut off your head and place your foot upon it?” he once asked, conjuring a somewhat sophomoric image for his target audience. “The price of god’s love is your head, and nothing less.” (This is a double entendre if there ever was one.) When piety is put above all else, fanaticism–in all its mindless zeal–can’t help but ensue.

The point is worth emphasizing: THE most prominent Islamic theologian of the Middle Ages was reactionary to the core. Tragically, Al-Ghazali’s invidious ramblings held prodigious sway in the centuries that followed his proselytization; as subsequent theologians (esp. the reactionary ones) ACCURATELY recognized that Al-Ghazali’s pablum was most in keeping with Mohammedism. Ironically, he almost single-handedly initiated the scourge of hyper-dogmatism that lead to the demise of Islam’s so-called “Golden Age”.

Rather than the occasional luminary redefining the Ummah, estimable figures (like Avicenna and Averroës) remained felicitous aberrations in an overwhelming trend of entrenched religionism. Even the best minds can only make so much headway in an environment fraught with systematically-enforced dogmatism.

The irony is that now, fundamentalists within the Ummah contend that the demise of Dar al-Islam (the waning of its glory-days that occurred after Al-Ghazali) was due to Muslims not being religious ENOUGH. (If only they’d been MORE doctrinal!) For the Iranian Grand Ayatollahs or Arabian Wahhabis or the Pakistani / Afghani Deobandis (e.g. the Taliban), utopia lies in bringing society back to the Dark Ages (read: Dar al-Islam’s heyday). Consequently, Salafism is their panacea.

The more fundamentalist strains of Islam today reflect–and seek to revitalize–the vehemently anti-intellectual legacy of Al-Ghazali. So long as this notorious Islamic theologian is held in high esteem (rather than denounced as a blight on the history of Islam), genuine reform in the Ummah will remain untenable.

Alas, when it comes to the history of Islam, Al-Ghazali was not an anomaly. He was but another figure in an on-going legacy. Other torch-bearers of Salafism Islam soon followed. As we’ll see, they were–one and all–Reactionaries, not revolutionaries.