The Universality Of Morality

July 24, 2020 Category: History, Religion

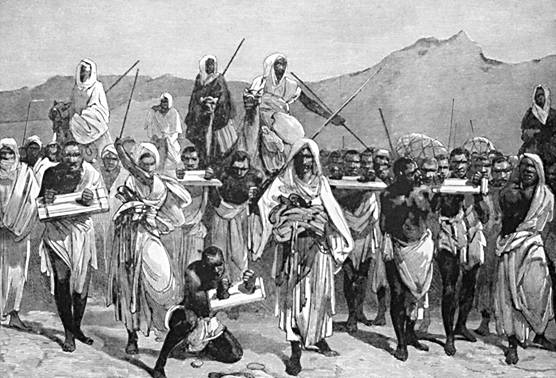

Slavery:

When it comes to the history of one group of people enslaving–or otherwise programmatically dominating / oppressing / exploiting–another group of people, we find that a pattern emerges. (Note: Here we are referring primarily to chattel slavery; but in this survey, it is worth including other forms of systematic persecution.) As it turns out, such iniquity tends to be perpetrated wherever cult activity is strongest–most notably: medieval regimes like Roman Catholic and Salafi. (Modern regimes like Nazi, Stalinist, and Maoist were concerned more with ethnic cleansing and other pogroms rather than with enslavement.) {25}

It is worth noting that this heinous practice has NOT been universal. For over THREE AND A HALF MILLENNIA (from the 20th century B.C. to their eradication by Spanish Conquistadors in the 16th century), the Mayans–and their antecedents–had no slavery. Their massive temple complexes were erected from voluntary labor; and there was little, if any, highly-concentrated wealth. That is: It was a relatively egalitarian society.

Nor was there chattel slavery in Pharaonic Egypt. Nor in Ancient Persia (though there was indentured servitude). Nor in the Kushan Empire. Nor in the Mongol Empire. And while there was a socially inequitable caste system, most of the Indian Empires (from the Magadha and Nanda Empires, through the Maurya and Gupta Empires, to the Maitraka and Chalukya Empires) did not have chattel slavery.

Barring genocide, chattel slavery represents what is probably the most egregious breach of Kant’s Categorical Imperative (discussed forthwith). And barring genocide, it is arguably the most flagrant betrayal of Marx’s “species-being” (also discussed forthwith). As it turns out, the biggest culprits have been those practicing fundamentalist versions of the three major Abrahamic traditions.

The willingness to enslave other people was sanctioned by the scriptures of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In the Torah, most notable are Exodus 21:20-21 and Leviticus 25:44-46, which actually ENCOURAGE the enslavement of those from other tribes (who are described as property). We are also told that beating slaves is fine, so long as the owner doesn’t beat them to death. As mentioned earlier, in chapter 31 of Numbers 31, Moses enjoins the taking of other tribes’ virgin girls as sex-slaves…while instructing married women to be killed. (For endorsements of slavery, also note verses 2-11 and 27-27 in Exodus chapter 21; as well as verses 10-15 in Deuteronomy chapter 20.)

Fellow Hebrews could also be enslaved. However, they were to be offered special dispensation–a caveat stipulated in Deuteronomy 15:12-13 and Leviticus 25:39-40. Thus: Don’t treat your own tribe with quite as much cruelty…in the event that you enslave THEM. {22}

In sum: Enslaving humans is fine, as long as you don’t do any work on Saturday.

When the Torah’s protagonist (Yahweh) notifies us that the most important thing we need to know about taking female slaves is that we should shave their heads before bedding them, we can be quite certain that the authors of the pentateuch (five books of Moses) were morally challenged. What the book most certainly does NOT do is proffer a compelling case for abolition.

Such moral bankruptcy continued into the New Testament. A clear endorsement of chattel slavery can be found in the Gospel of Matthew (18:25 and 24:51) and of Luke (12:47). Also notable are Saul’s letter to the Ephesians (6:5-9), to the Colossians (3:22 and 4:1), and his first letter to Timothy (6:1-3); as well as Peter’s first letter (2:18-20). That’s not all. In his letter to the Galatians, Saul wrote: “The slave might continue to serve his master; male and female shall each retain its proper role in the on-going stream of life.” (Strange how Saul was not quoted in the civil rights movement.)

If the Creator of the Universe, in all his infinite wisdom, really believed in equal rights for all mankind, one would think that he would have mentioned something–even just once, in passing–about this issue in one of his holy books. Alas. His mind was more occupied with such pressing matters as witch-craft, mixing meat with dairy, doing domestic chores on the Sabbath, and the intolerable occurrence of women speaking up in church (as expressed in Saul’s first letter to the Corinthians 14:34-35).

Hence the Vatican’s endorsement of the practice in the “Decretum of Gratiani” [Decretal of the jurist, Gratian], which was codified in the “Concordia Discordantium Canonum”: part of the Corpus Juris Canonici of the 12th century. Tellingly, the Vatican only had qualms with people (spec. with Genoese and Venetians) selling men, women, and children to MUSLIMS (spec. the Mamluks). And it is also very telling that slavery was not redacted from the Roman Catholic code of canonical law until 1917 (in the midst of the First World War).

According to the Hadith record, Mohammed of Mecca encouraged slavery: Bukhari’s Hadith no. 371, 2403, 2415, 2592, 3145, 4121, 4234, 5191, 6161, 6202, and 6603. He even proclaimed that gifting slaves was better than manumitting slaves. (Generally, whenever a man was abjured to manumit a slave, it was done as punishment to the slaver, not for the benefit of the slave.) Slaves were seen as property. This is illustrated by the declaration that there needn’t be any tax paid for either a slave or a camel (Bukhari no. 1464). And in a discussion about trading animals for animals, we find that one Arab slave was worth two black slaves (Sunan an-Nasai no. 4621; alt. 5/44/4625).

But why such glaring dereliction on such an elementary point? It is no stretch to contend that the Abrahamic deity could have easily included “Thou shalt not enslave anyone, ever, no matter who they might be” in the Mosaic Decalogue. {5} He didn’t. This is a problem. Especially considering the proscription against mixing meat and dairy seemed to have been a more pressing matter for the book’s authors.

If one is looking for a compelling case against slavery, one will wind up empty-handed when seeking it in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, or the Koran. When eating shell-fish and men laying with other men top the list of abominations, it is quite clear that the authors of the Torah had their priorities severely askew.

A typical retort to this point is: “But you see: Back then, mankind wasn’t ready to eliminate slavery.” Were the Hebrews really so dimwitted that they would not have been able to grasp such a simple proscription? We might look back to the late 3rd millennium B.C., when the code of Ur-Nammu declared that domestic servants should be allowed to own private property, to buy their freedom, and even to run their own businesses. Indeed, chattel slavery seems to have been quite rare in Sumer. Evidently, people were sufficiently insightful to recognize such problems in the Bronze Age.

So are we to suppose that the Sumerians simply more astute than the Hebrews?

But that’s not all. In the 18th century B.C., the code of Hammurabi stipulated conditions under which slaves should be freed (including when they married non-slaves). It permitted slavery under certain conditions, but had strict rules against the abuse of slaves. Moreover, slaves were always given the chance to purchase their own manumission.

And as already mentioned: While there may have been cases of indentured servitude in Pharaonic Egypt, there was no chattel slavery. Never were Hebrews–or anyone else, for that matter–enslaved in Egypt. (The pyramids at Giza were built primarily by paid laborers, who resided in their own domiciles; though there was likely indentured servitude involved.) So, yes: The vilified Pharaoh (likely Ramses II) was more enlightened on human rights than were the Hebrews he supposedly held in captivity (which, in reality, didn’t really happen).

According to Abrahamic lore, that would ALL have been before the Abrahamic deity delivered the “Aseret ha-Dibrot” / “Aseret ha-Divarim” to Moses (Yahweh’s compact with his chosen tribe: the Hebrews). So when the issue FINALLY WAS broached, what did Mosaic law stipulate? That the enslavement of human-beings was wrong? Nope. Instead, we find gems like Exodus 21:20-21 and Leviticus 25:44-46, which notify the Israelites that slaves are, indeed, their property. (Again: The former even gives permission to beat slaves to within an inch of their lives.) {5}

The supposition that Mosaic law is THE GOLD STANDARD of moral guidance is, then, not only preposterous; but mendacious.

What of the Exilic period (when the Torah was actually composed)? As it turns out, the Achaemenids–who ruled across Persia and Mesopotamia–had relatively strict taboos against enslaving populations; and seem to have forbidden chattel slavery. (The Hebrews in Babylon were not enslaved; and if the ruler, Nebuchadnezzar, would have opted to enslave ANYONE, it surely would have been them.) The Persians’ prohibition against chattel slavery continued on through the Parthians and Sassanians–as discussed in my essay on “The Long History Of Legal Codes”.

Ok. Well, then, what of Greece? In the 5th century B.C., the Athenian writer, Euripides of Salamis stated: “The slave is capable of being excellent in every way and truly equal to the free-born man.” In the 4th century B.C., the Athenian writer, Alcidamas of Elaea stated in his “Messeniakos”: “God made all men free. Nature has made no man a slave.” Of course, this was not the over-riding sentiment of the entire planet at the time; but humanist principles were percolating beneath the surface throughout Classical Antiquity. And, clearly, such Progressive thinking was based on insights that had nothing to do with the Abrahamic deity.

People everywhere were capable of seeing what the authors of the Abrahamic scriptures couldn’t. And that capability existed since time immemorial.

Ok, then. But what of the Far East? In the 3rd century B.C., Mauryan Emperor Ashoka of Pataliputra [Bihar] (a.k.a. “Ashoka the Great”) broke new ground in the governance of civil society. The Edicts of Ashoka forbade slavery across India. Ashoka’s (Buddhism-inspired) doctrine of “dhamma” [the Pali version of the Sanskrit, “dharma”] was arguably the first declaration of human rights. And it was likely the first explicit articulation of humanism–emphasizing, as it did, tolerance of others and the dignity of every human qua fellow human, irrespective of who they might be. (Again: See my essay, “The History Of Legal Codes”.) The notion of “ahimsa” (that no one has the right to harm another sentient being) actually dates back FOUR MILLENNIA–specifically in the Jain tradition.

Also in the 3rd century B.C., China’s Qin dynasty became the first government in history to (attempt to) formally abolish slavery; though the success was short-lived. Later, in the 1st century A.D., Emperor Wang Mang campaigned to abolish the slave trade…again, without long-term success.

In the 1st century B.C., the Roman Stoic philosopher, Marcus Tullius Cicero of Arpinum propounded the humane treatment of slaves, articulating this position for far better reasons that anyone would until Thomas Paine wrote his treatise against slavery in the 18th century A.D.

Indeed, the Stoics advocated for universal education–including for women, for the poor, and–yes–even for slaves. A respect for mankind means that everyone is given access to public resources, a chance to pursue excellence…and achieve eudaimonia.

In the early 1st century A.D., Lucius Annaeus Seneca of Cordoba (“Seneca the Younger”) advocated for the civil rights of slaves–holding that human rights extended to ALL humans, no matter how low their socio-economic status might happen to be. Along with fellow Stoic, Gaius Musonius Rufus of Etruria, Seneca was against ANY maltreatment of slaves–including striking them or using them for sex. Seneca had his interlocutor declaim: “He is a slave!”… to which he replied, “No, he is a human being.”

Contrast this penetrating (and heterodox) moral insight to the moral depredations of the Halakhah and Sunnah, in which slavery is assumed as a matter of course–and is thus enthusiastically endorsed by those who codified each creed (replete with ROUTINE battery, rape, and slaughter).

In the 140’s, Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius enacted legal measures to facilitate the enfranchisement of slaves. He also promoted the principle of “favor libertatis”, which gave (purportedly) manumitted slaves the benefit of the doubt when there was any doubt about the legitimacy of the claim. These laws mandated punishment of a master when he killed his slave. Meanwhile, any abused slaves could be forcibly transferred to another master (by a proconsul).

The question, then, is: Such figures took this noble stand based on WHAT? Egypt, Greece, Rome, Persia, India, and China were surely places of which the Creator of the Universe was aware. So why the hesitation with the Israelites who lived between Moses and Solomon…and thereafter with the Judeans during the Iron Age…and then with Maccabees during Hasmonean rule…and then with the Pharisees and Sadducees during the Herodian era…and then with the first Christians during Late Antiquity…and then with the Sephardim engaged in the Mediterranean slave-trade throughout the Middle Ages? (Jews were active slavers from Andalusia to Bohemia until the modern era.)

In light of all this, we find ourselves running out of possible excuses. To reiterate: The plea, “But at the time, the Hebrews were not capable of eradicating slavery” is groundless. In fact, such special pleading reeks of an inadvertent anti-Semitism–based as it is on the passive bigotry that is indicative of lower standards. Expectations for basic humanity must be universally applied. Certainly the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Persians, Indians, and Chinese were not (inherently) more astute than those dedicated to Mosaic law.

Alas, even in the advent of the Talmudic era (starting, it turns out, at the same time as Mohammed’s ministry; i.e. the early 7th century A.D.), the institution of slavery persisted. It is quite telling that, throughout the Middle Ages, the Radhanite Jews of the Maghreb who were active impresarios of the Mediterranean slave-trade…in concert with the Moorish (Islamic) corsairs. It is no coincidence that in medieval Arabic, the SAME WORDS were used for slave as for black African: “[h]Abib” / “Zanj”. “S-Da” means black: a reference to the subaltern Nubian people who were eventually enslaved. This lexeme was the basis for “Sudan”. To THIS DAY, Salafis harbor a malignant racism against Nubians; hence the recent genocide in Darfur.

Strange how–even then–those professing fealty to the Abrahamic deity had STILL not gotten the memo that there may have been some moral issues with the enslavement of humans.

As it turned out, the Muslim world would end up boasting the largest slave-trade the world had ever seen–stretching from the Barbary Coast to China. This was constituted not only of the Barbary pirates (who enslaved Europeans around the Mediterranean Sea), but of the mercantile dealings out of the city-State of Ormuz (which conducted the slave-trade between the African Horn and Swahili coast, Arabia, Persia, and into the Far East). {8}

So were there ANY moral inroads made during the Middle Ages? As it turns out: yes. Upon inaugurating the Ming dynasty in the 14th century, the (Buddhist) Hong-wu Emperor made a serious attempt to abolish slavery in China; yet his efforts were–ultimately–to no avail. Suffice to say: His laudable endeavor was not inspired by Mosaic law.

Back in Dar al-Islam, Muslims sold slaves primarily to other Muslims; though the Barbary slave-trade dealt regularly with the Sephardim of the Mediterranean basin–who were ALSO always eager to sell / purchase slaves. The Barbary pirates even sent slaves to Asia–as documented by the Chinese chronicler, Duan Cheng-shi in the 9th century. Donning the crucifix, Italian merchants (esp. the Genoese) purchased slaves from Mongols (who did not themselves enslave anyone, but were willing to hand over prisoners of war to slavers in a quid pro quo). They also purchased slaves from Kipchaks and Slavs, and sold them to the Mamluks. And as for the Radhanites? Well, they were willing to sell slaves to pretty much anyone willing to pay the right price.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Dar al-Islam hosted the planet’s most far-reaching slave-trade–vestiges of which can still be found in West Africa and on the African Horn. (To reiterate: Slavery REMAINS rampant in Islamic theocracies to the present day.) Century after century after century, slavers thrived—from the (Roman Catholic) Genoese on the Italic peninsula to the (Jewish) Radhanites on the Barbary Coast to the (Muslim) Ottoman slave markets of Kaffa on the Black Sea. During the Crusades, the (Roman Catholic) Franks engaged in the systematic enslavement of indigenous peoples. Of course, the Muslim world was arguably the most active in the slave-trade through the Middle Ages. From its inception in the 7th century, enslavement of “kuffar” (non-Muslims) had been codified in doctrine. Black slaves where referred to as “Zanj”, Turkic slaves were referred to as “mamluks”, and Slavic slaves were referred to as “saqalibi”. Starting in the 16th century, Christian Europeans would initiate the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which eventually outpaced the (waning) slave industry in Dar al-Islam.

Meanwhile, slavery was rampant in the Christendom until the 19th century. The standard rationalization for the practice was BIBLICAL. In 1453, (Portuguese) Prince Henry’s biographer, Gomes Eanes de Zurara (who was the commander of the crown’s “Military Order of Christ”) published “The Chronicle of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea”. In it, he put forth an official defense of the African slave-trade–couching claims of black inferiority in explicitly religious terms.

So to attribute the abolition of the heinous practice to Judeo-Christian “values” OR to Islam is patently absurd. Abrahamic religion was certainly not helping.

Through the Middle Ages, up to the 19th century, it was the most ardent proponents of the Abrahamic religions that were the primary culprits—first the Muslims and Radhanite Jews across the Mediterranean, then Christians with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. When the case was (finally) made against slavery, it was based on eminently SECULAR principles. In 1759, when the (secular) Scottish philosopher (and political economist), Adam Smith held that all slavery proceeds from a “tyrannical disposition” (“The Theory Of Moral Sentiments”, p. 206-207), the Church of Scotland had nothing to do with it. At the beginning of 1775, when Paine published “African Slavery In America”, religious dogma played no role in his argument for abolition.

Ok, fine. But what about William Wilberforce? After all, he was a Christian who–at the beginning of the 19th century–advocated for abolition, was he not?

Indeed, he was. This (rightfully) celebrated British Methodist may have been the primary figure–at that particular time–when it came to efforts to bring the slave trade to an end. But he did not come upon this position ex nihilo. Like the reverend, Martin Luther King Jr. would over two centuries later, Wilberforce articulated his position in the idiom of the time; but he did NOT use church doctrine as the ultimate basis for his lofty enterprise. In fact, he and his fellow abolitionist Thomas Clarkson (a liberal Anglican) BOTH had a British fore-runner to inspire them (and, for that matter, to provide the philosophical groundwork for their noble stand). That trailblazer was none other than the secularist, Thomas Paine (who penned “The Rights Of Man” in the 18th century).

The degree to which either Wilberforce or Clarkson deigned to attribute their passion to pursue this laudable endeavor to their Faith is anyone’s guess; but it most certainly did not DEPEND ON their religiosity (qua subscription to ancient dogmas). Their position was not based on scripture…because they COULDN’T base it on scripture. Indeed, it was impossible for ANYONE to make the case on religious grounds–considering the Gospels of Matthew (24:51) and Luke (12:47). Compound those passages with Saul’s letter to the Ephesians (6:5) as well as his first letter to Timothy (6:1-2), and Wilberforce had no recourse to scriptural backing. This disjuncture with doctrinal fidelity is, after all, what made him such maverick. He was an iconoclast, not a champion of piety.

Wilberforce was no Reactionary. The heterodox preacher appealed to basic decency; not to theology. He knew full well that slavery was unequivocally supported throughout the Bible; so he was only able to make his plea about “Christianity” insofar as the creed extolled compassion for the downtrodden. It is no coincidence that the vast majority of his religious allies were QUAKERS: by far the LEAST doctrinal–and consequently, the least tribalistic–of devout Christians.

The same was the case across the Atlantic. In America, the most avid NON-secular abolitionists were the Quakers. (Recall that Martin Luther King’s right-hand man, Bayard Rustin, was a Quaker.) In the event that ANY religious person advocated for abolition (or for civil rights in general), it was due to their conscience, not to their religious zeal.

Tellingly, Wilberforce’s most virulent OPPONENTS in Parliament were fellow Christians…who, sure enough, justified slavery with a panoply of religious arguments; and ample scripture to back it up. In other words, it was only when Wilberforce BUCKED his religion (while still working in the spirit of the messages propounded by JoN) that he was able to take the noble position he took.

In the end, the campaign to end slavery finally occurred not due to the existence of this or that sacred doctrine. Wilberforce took the anti-slavery position IN SPITE OF his religiosity, not because of it. If anything, the response to Wilberforce and Clarkson should have been: “It’s ABOUT TIME a Christian finally took a stand against slavery.” Alas. Christianity has very little to do with what JoN actually preached; so the fact that Christians so ardently endorsed the practice surprised absolutely no one.

Bottom line: Speaking out against slavery in England–or ANYWHERE in Europe, or in America–entailed challenging received wisdom; and bucking religious precedent. It was by rebutting institutionalized dogmatism that Christian abolitionists made their case in the United States.

To recapitulate: It is no coincidence that the majority of such Progressive-minded Christians were Quakers–again: the least dogmatic and least tribalistic of all the world’s denominations. To attribute their cause to their religiosity, then, is to completely miss the point.

Whenever headway was made in the realm of civil rights, it was always made in defiance of religious dogmas. Consequently, Jews and Christians were faced with a quandary when it came to abolishing slavery. (Many Muslims STILL ARE facing the quandary; as the Sunnah clearly endorses the practice.) For votaries professing Biblical tenets found themselves deigning to condemn something that their godhead CLEARLY thought was perfectly acceptable. This predicament was even more pronounced when it came to Islam: a Faith predicated on programatic subjugation. {4}

So what of the role of secular thought in exposing the iniquities of slavery? A good place to start is Thomas Paine–who penned “African Slavery In America” in 1775. The Marquis de Condorcet penned “Reflections On Negro Slavery” six years later (in 1781). Later, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published the abolitionist anthology, “Poems On Slavery” in 1842. What did these three men have in common? They were all non-religious, and were all castigated for speaking out for civil rights. Castigated by whom? As it turns out, mostly by RELIGIOUS people. (Recall that John Adams–arguably the most religious of the American Founders–served as an attorney FOR slave-holders.) Meanwhile, it was Paine and Benjamin Franklin (both consummate secularists) who established the first American Anti-Slavery Society (which would later enjoy a resurgence in the 1830’s). In the late 18th century, we should also note that the most important abolitionists were SECULAR.

In addition to those just mentioned, Alexander Hamilton (who might be characterized as a secular Episcopalian) was a key member of the New York Manumission Society. While John Jay was notable for attributing his participation in this society to his religiosity, this was likely a rationalization–and ingratiating justification rendered post hoc to tie his moral sense to his Faith. The evidence was overwhelming that no religious Faith was required to engage in the enterprise.

Ratios here are telling. For every (non-Quaker) Christian abolitionist, there were LEGIONS of Christian ANTI-abolitionists…and still more abolitionists who were secular.

Note that Thomas Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration of Independence (the letter addressed to King George III of England in the summer of 1776) included the following indictment:

“This king has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating the most sacred right of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, capturing them and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere to incur miserable death in their transportation. This warfare on humans is the opprobrium of infidel powers. The CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain is determined to [maintain] an open market, where men should be bought and sold” (caps in the original).

In other words: Jefferson saw Christianity as the salient feature of the monarchy’s iniquity on this score. (The passage was omitted from the final draft due the pre-established condition of unanimity. 2 of the 13 colonies–South Carolina and Georgia–dissented because they did not want the trans-Atlantic slave-trade to be listed as a grievance.

In his “Notes On The State Of Virginia”, Jefferson weighed in on the iniquities of slavery, which would regrettably continue to be practiced (for the time being): “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep for ever; that considering numbers, nature, and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune–an exchange of situation–is among possible events; that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.”

(Ancillary note: The mis-guided notion that the American Republic was FOUNDED UPON slavery is tremendously disingenuous. Not only is it historically fallacious; it imputes motives to the Founders that clearly did not exist. The contention that the revolution was done IN ORDER TO SUSTAIN slavery would have come as a surprise to Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton…who were adamantly against the practice, even as they championed the revolutionary cause; and actively took measures to vanquish the heinous practice, which they saw as a stain on the founding of the new Republic.)

Putting slavery aside, we mustn’t forget pivotal figures in the civil rights movement who were avowed secularists. Starting in the 19th century, we might recall female American icons like Harriet Tubman, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Ida B. Wells. All secular. There were also notable men like A. Philip Randolph, Robert Ingersoll, William Lloyd Garrison, and W.E.B. Du Bois. All secular. Such luminaries did not require religious dogma to make the points they made about civil rights. In fact, each of them eschewed religionism IN ORDER TO make the points they made.

Obviously, even when religionists saw the ills of slavery, they invariably expressed their advocacy in the terms they understood. Certain idioms resonated with certain communities, so those were the idioms in which the ideas were couched. It does not follow from this that the ultimate basis for abolitionism could be found in the sacred doctrine with which any given person may have been affiliated. On the contrary, it was the ability to rise above dogmatism and think for themselves that enabled people to (finally) embrace civil rights. {6}

To ascertain the degree to which we might attribute a “liberal” Christian’s Progressive views to his religiosity, we might ask: Did Martin Luther King Jr. promote civil rights, protest the war in Vietnam, and advocate for organized labor because of the tenets of BAPTISM? Of course not. Is this to say that religion was irrelevant? No. It invariably played a role in ANYTHING that occurred; as it was a significant part of social life.

The role of Christianity in America’s abolition movement illustrates this point very well. In America’s antebellum South, churches were bastions of dissent–and sanctuaries from bigotry–for virtually all African Americans. Federations of churches were even more effective than solitary congregations–demonstrating the veracity of the adage about strength in numbers. For it was THOSE institutions to which black people turned during the tragically protracted Jim Crow epoch. Hence the role of the Southern Baptist Convention and the Southern Christian Leadership Council–which proved integral to the civil right movement of the 1960’s. (Martin Luther King Jr. affiliated with both. King’s compatriot, Bayard Rustin, was a Quaker.)

Context is important here. The SBC was originally formed to protect the entitlements of slave-holders. That it eventually underwent reform, and became a vehicle for the empowerment of African Americans (as well as a mechanism for orchestrating protest), was in spite of–not thanks to–the received doctrine of its churches. It’s worth noting that other key organizations in the civil rights movement were either secular (CORE, the NAACP, the SNCC, and the ACLU) or trans-religious (as with the International Fellowship of Reconciliation; which included Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and Freethinkers).

In assaying the relevant history, it is important to recognize that the raison d’etre of these ecclesiastic federations was not the imposition of doctrine. Their prime directive was to empower their members–primarily with respect to the promulgation of civil rights. In other words, such religious organizations were primarily there for galvanizing, not for evangelizing. The black community was their base, not their target. Take away all the theological musings, and the places of worship would have served their purpose just as well…or, perhaps, even better. It was the communal aspect that was salient, not the dogmatic aspect.

Meanwhile, it’s worth asking: How many WHITE southern churches were fighting for the rights of blacks? Almost none. Clearly, being a member of a church was not the pivotal factor; it was being a member of an oppressed group. To wit: It was a matter of having recourse to only one (dependable) mechanism to pursue enfranchisement: the local church.

In the south, black churches naturally became the emotional and social engine behind what was a moral–and ultimately legal–argument about civil rights for blacks. To reiterate: This happened in churches by default. (That is to simply to say: Due to the circumstances, such venues could not have been anything other than the churches. There was no viable alternative.) The local church offered a way for blacks to support each other in trying times…when virtually any other context for a large gathering would have been prohibited by the authorities. During each service, the message was uplifting: Take heart, for deliverance is at hand. Considering all this, it would have been odd for a black southerner to NOT have participated.

And so it went: Churches served as communal centers for a marginalized group. Their power was in coming together; and, in doing so, offering a leg up to those for whom nobody else seemed to care. The local church was the only means of solace that such people had available to them at the time. And–more importantly–it was an institution that gave blacks a sense of empowerment. The local church provided a place to sing, to count one’s blessings, to congregate without drawing the suspicion of municipal officials (read: without fear of police). It was a safe haven in a hostile world: just what the doctor ordered.

So were churches valuable because of Christianity per se? No. They served as a mechanism for solidarity–and as the only dependable support network available to non-whites in the Jim Crow south. In other words, the local black church provided southern blacks with all the things that they desperately needed. Consequently, churches would inevitably play an integral role in ANY movement blacks sought to undertake.

Sacred doctrine was beside the point. The congregations’ power was in being uplifting to those who may have otherwise been lost at sea; furnishing congregants with a poignant vernacular to express grievances and aspirations. And in order to coordinate their efforts for the greater cause, such congregations THEMSELVES needed to band together. Ergo the SBC and SCLC.

As they were uniquely primed for mobilizing nascent activists, it was these ecclesiastic federations that were repurposed for the task at hand. Their mission was to promote civil rights; not to promulgate ancient dogmas. Member churches served as a heaven-send for America’s southern blacks, who were looking for one thing more than anything else: hope.

Such reassurance was much needed. In no other place could one find the crucial message: “You are not alone. And in spite of your plight, remember that god loves you.” (The Promised Land is nigh, so forge onward.) Black people had needed to look forward to a “Promised Land” since the earliest years of their enslavement; and this was just as true during the Jim Crow era.

After all, a persecuted people needed SOME “good news”; ANY “good news”. And it was possible to believe in the “Gospel” during even the most trying of times; as it involved a destination that was not of this world. It was a way to endure tribulation. In a sense, the role religion played for American blacks during the Jim Crow era informs us of the role religion ultimately plays for ANYONE. It was an illustration of the practical purposes religion serves.

The lesson here is clear. To attribute the brave civic activism of blacks who happened to identify as Christian to their CHRISTIANITY is to not give them enough credit. Moreover, it is to completely miss the point of what they were doing and why they were doing it. Their Faith imbued their cause with a shared narrative. It was a way to galvanize those who may have otherwise been distraught, discouraged, and completely disenchanted with life.

As with most things, religion is there to help make sense of things when nothing seems to make sense; to bring people together (especially those who are disaffected), and coordinate their efforts.

But there’s a catch. Religion can be used for whatever purposes one wishes. To repeat: Southern WHITE churches vociferously FOUGHT civil rights. So suggesting that it was religion PER SE that was responsible for civil rights is completely erroneous.

To conclude: In pre-civil rights America, the local black church was–logistically speaking–the optimal place for a marginalized community to effect solidarity. The particular details of this or that sacred doctrine was beside the point. For, in the end, a religion is whatever its adherents make it (according to their aspirations)–be they southern blacks fighting for emancipation or racist WASPs seeking to rationalize the oppression of other races.

Clearly, it is not Christianity per se that we should thank for the civil rights movement. It was humans coming together to stand up for what was right, regardless of what this or that scripture might have said. Any civil rights activists who happened to be religious shared the same impetus–and ultimately worked from the same precepts–as secular activists. Both proceeded from an axiom that transcended social constructs.

This common ground enabled ALL abolitionists qua abolitionists to overcome sectarian divides. In other words: The driving force of the movement existed independently of religiosity; and the underlying principles did not come from any specific book.

Tying human rights to this or that people’s creed / culture does a grave disservice to all the other peoples of the world; and risks the hyper-romanticization of the designated creed / culture. One is forced to proceed as if one’s own culture were somehow pre-ordained to be the world’s quintessential culture. The notion of a “best culture” makes absolutely no sense whatsoever; as no culture can be assessed wholesale (see the Postscript to “The Progressive Case For Cultural Appropriation”).

When it comes to the history of programatic oppression, another fact is worth noting: Over the epochs, had ANY of the world’s slavers honored one of the simplest moral axioms ever conceived, then no group would have ever felt entitled to enslave another group. It is to this “Golden Rule” that we now turn.