The History Of Salafism I

May 5, 2020 Category: History

Postscript 2:

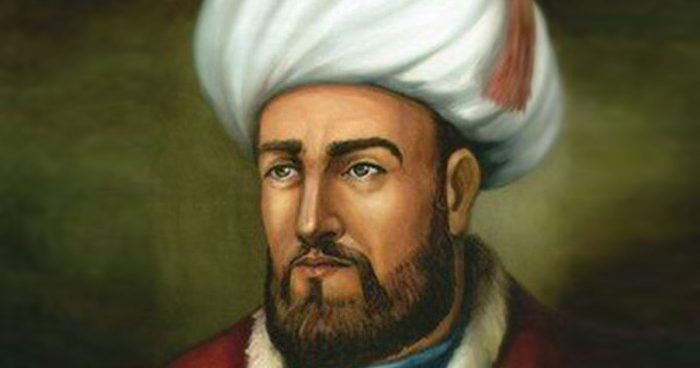

A Response To Objections To My Characterization of Al-Ghazali

In Islamic apologia, Abu Hamid al-Ghazali of Tus is portrayed as a champion of intellectual curiosity. This is asserted about a man who stated that laymen “should be forbidden–as much as possible–from perusing philosophical works.” In fact, Al-Ghazali was the consummate dogmatist who vociferously sought to stifle intellectual activity.

But how can we be so sure? In the main body of this essay, I outlined much of the evidence for this thesis. In light of objections leveled by Islamic apologists who espouse a more charitable characterization of this Muslim icon, some elaboration may be in order.

Al-Ghazali’s doctrinal mindset can be explained by the fact that his mentor in Nishapur was Dhia ad-Din Abd al-Malik ibn Yusuf of Juwayn, Khorasan (a.k.a. “Al-Juwayni”), who subscribed to the Shafi’i “madhhab” (school of jurisprudence) and the Ashari approach to Islamic theology. Al-Juwayni was hostile to ANY speculation for ANY reason. So far as he was concerned, all thinking must strictly hew to the Sunnah. Want answers? Look to scripture. Period. This is made clear in his “Irshad ila Qawati al-Adilla fi Usul al-I’tiqad” [Guide To Conclusive Proofs For Principles Of Belief].

Al-Ghazali was eventually employed by the Seljuk minister, Nizam al-Mulk in Baghdad; to be headmaster at the “Nizamiyya” (government-commissioned madrasas). The “Nizamiyya” were effectively indoctrination facilities; not universities. Al-Ghazali was unwavering in his Koranic literalism—as made clear in his screed: “Fada’ih al-Batiniya” (a virulent indictment against those who posited “batin”). As luck would have it, the powers that be had an ax to grind with “Batiniyya”—that is: those who were open to not taking Koranic text literally (spec. the Shiite sect known as the “Isma’ilis”). So, at the time, he was a natural choice for the job.

Pursuant to his endorsement of the Shafi’i “fiqh”, Al-Ghazali secured a position as advisor to the Reactionary Seljuk vizier, Nizam al-Mulk–who’s hometown, Tus, was the same as Al-Ghazali’s. In keeping with this vocation, Al-Ghazali came to be a strident opponent of the far more liberal Ishma’ili approach to Faith (primarily affiliated with the Fatimids).

In his memoire, “Deliverance From Error”, Al-Ghazali announced that his certainties were derived not from “constructing a proof or putting together an argument”; but were instead the result of “god casting light into my breast.” He concluded, that said “light is the key to knowledge.” He then scoffed at what he dismissed as “unimportant sciences”…which, he averred, “are useless in the pilgrimage to the afterlife.” Recall that he stated: “The price of god’s love is your head, and nothing less.”

Al-Ghazali conceded that, in having briefly allowed himself to engage in free inquiry, he feared displeasing god; and consequently being cast into hellfire. So he sought to adjust his thinking accordingly. While supplication became his sine qua non, free-wheeling speculation and critical reflection became verboten.

Here was a man who seemed existentially disoriented, even lost. Toward the end of his life, Al-Ghazali opted to follow his brother into Sufism, whereupon he became a vagabond / hermit for over a decade. This “tasawwuf” did not preclude his Salafism; it merely demonstrated that he was fumbling around in the dark, groping in desperation for something to hold onto.

As with many who become smitten with mystical mumbo-jumbo, Al-Ghazali managed to find meaning in esoterica. It was at that juncture in his life that his ultimate goal became–in his own words–the “ihya” [revival] of the “ulum ad-din” [principles of the Islamic way of life].

Mysticism is not mutually exclusive with fanaticism; it merely gives one’s religiosity a glossy patina of mystique. The fact that some Salafis denounce Sufism is rather beside the point. The distinction is more about branding–and stylistic choices for observance–than it is about the underlying pathology. Religious fundamentalism is religious fundamentalism. It’s not for nothing that Al-Ghazali’s teachings had a profound influence on Ibn Taymiyya: a Salafi who was NOT a Sufi.

Al-Ghazali’s seething contempt for great Muslim thinkers like Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Al-Farabi is very telling. (He expressed nothing but disdain for such luminaries in his “Incoherence Of The Philosophers”.) He is known for having said: “The ‘munafiq’ looks for faults; the ‘mumin’ looks for excuses.” * In other words: Those who are insufficiently pious try to find defects in the Sunnah, whereas supplicants use rationalizations for their beliefs. This is TRUE. The problem is that Al-Ghazali saw it as a vice for the former and a virtue for the latter (rather than the other way around).

Elsewhere, Al-Ghazali mused that “if those who do not possess ‘ilm’ were to avoid scholarly discussions, all disagreement would end.” Again, TRUE. Apparently, he saw this hypothetical eventuality as a panacea; and lamented that non-Muslims were inclined to weigh in on important matters. So WHAT OF this vaunted “ilm” of which he spoke? As it turns out, it is NOT the equivalent of what we now refer to as “knowledge”. Al-Ghazali was unequivocal on this point. He averred: “The essence of ‘ilm’ is to know what obedience and worship are.” (For more on the buzz-term, “ilm” and why it does not correlate with the post-Enlightenment sense of knowledge, see the Appendix below.)

The point is worth reiterating: Al-Ghazali did not believe in causation. His thinking was as follows: Only god brings things about; so the only things that happen, happen according to god’s will. That’s all anyone needs to know. Any other explanation is superfluous.

Al-Ghazali’s anti-intellectualism was inseparable from his illiberalism. This was exemplified by his unabashed misogyny. In his book, “Revival Of The [Islamic Way Of Life]”, he stated that a woman “should remain in the inner section of her [husband’s] house and tend to her spinning. She should not enter and exit [that section] excessively. She should speak infrequently with her neighbors and visit them only when the situation requires. She should show deference to her husband in his absence and in his presence. She should seek his satisfaction in all affairs… She should not leave his house without his permission. When she goes out, with his permission, she should conceal herself in tattered clothing…being careful that no stranger hear her voice or recognize her… She should be ready at all times for [her husband] to enjoy her whenever he wishes” (Book 12: On The Etiquette Of Marriage). The sequestration of women in the Muslim world follows this precedent…which can be traced back to the earliest days of Islam. Recall that the Koran is addressed explicitly to men (a matter I explore in Appendix 2 of my essay, “Genesis Of A Holy Book”).

We should recall that, for Al-Ghazali (as with all religious fundamentalists), piety was inextricably tied with fear (to wit: fear of god)–a conflation that is captured by the term, “taqwa”. This defective epistemology is based on neurosis rather than on erudition.

It is worth noting that not everything Al-Ghazali said was objectionable. He was against avarice–noting that the only thing that one truly owns is that which cannot be lost in a shipwreck. He was against venality–impugning those who can be paid to change their opinions. Laudable as such positions are, they are not incompatible with religious fundamentalism. After all, even the most fanatical Puritans tend to be non-materialistic. Meanwhile, there is technically no corruption in North Korea. True Believers are neither conspicuous consumers nor grifters; but that does not absolve them from the detriments of their other dysfunctions.

So how might we cultivate a thorough understanding of this oft-lauded figure?

Let’s review. In his “Tahafut al-Falasifa” [Incoherence of the Philosophers], Al-Ghazali made his case against, well, PHILOSOPHERS, by contending that since there was no unanimity in the world of philosophy, ALL those who engaged in philosophy must be wrong. Hence it was only religion (spec. Islam) that had legitimate claim on Truth. He thus took the (forced) conformity and (forced) unanimity of a religious community as a sign of its credibility. Those engaged in philosophy or science could not possibly have been on the right track, as they were always disagreeing with one another!

Tellingly, Al-Ghazali’s two biggest targets—after Plato and Aristotle—were the two greatest thinkers in the history of Islam: Ibn Sina (“Avicenna”) and Al-Farabi.

So why bother talking about him? Lamentably, the majority of Islamic apologists today—from Mark Hanson to Timothy Winter—think that Al-Ghazali was the cat’s pajamas; or at least they pretend to think so. This state of denial is de rigueur in much of the Ummah. When most Muslims inquire about Al-Ghazali, it comes as no surprise that they are often treated to gushing encomia rather than serious analysis. Rather than a Reactionary, Al-Ghazali is routinely touted as a luminary. Such pablum is typically offered by charlatans posing as “scholars”—as with Hanson and Winter. This is a reminder that religious apologia thrives in a vacuum of critical thinking.

It beggars belief the pablum with which denizens of Dar al-Islam are systematically inculcated. Such inculcation is carried out by dishonest actors who masquerade as serious thinkers. Why? The likes of Hanson and Winter (a.k.a. “Hamza Yusuf” and “Abdal Hakim Murad”) are thoroughly convinced that, in return for their unstinting piety, they will eventually be treated to a coterie of buxom, wide-eyed virgins in a celestial paradise. As a consequence of this reverie, a raft of risible fictions are routinely propounded—among them: the glowing portrayal of Al-Ghazali.

Pretending that a dogmatic thinker—who was expressly anti-philosophy—was somehow a PHILOSOPHER is absurd. Alas. When it comes to Al-Ghazali, such misapprehension is commonplace; which explains why religious fundamentalism subsists.

Though a complete dissection of every page of his works would be a pointless venture, it’s worth perusing Al-Ghazali’s oeuvre on “logic” (“mantiq”) and “knowledge” (“ilm”). There were three notable books that dealt with such matters:

- The “Ihya Ulum ad-Din” [Revival Of The Knowledge Of The (Islamic) Way Of Life] (often mis-translated as the revival of “religious sciences”, a nonsensical phrase) is his magnum opus. Book 2 of this work is helpfully entitled: “Qawa’id al-Aqa’id” [Principles Of The Creed], a far cry from principles of SCIENCE. This work is a reminder that Al-Ghazali was, above all, a “mu-jaddid”—that is: a religious REVIVALIST. (The sobriquet means “one who effects tajdid”.) As with most proselytizers, Al-Ghazali was adamantly against (genuine) philosophy; so devoted his exposition to doctrinal matters. The work was a dogmatic splurge from cover to cover. **

- In the “Mi’yar al-Ilm fi Fan al-Mantiq” [Measure Of Knowledge In The Art Of Logic], he attempted to outline the standards / conditions for “ilm”. For Al-Ghazali, the only legitimate “ilm” was theological knowledge: an ersatz “ilm” known as “ilm al-kalam” (which effectively means: familiarity with doctrine—as explicated in his “Iljam al-Awam an Ilm al-Kalam”). It makes sense, then, that in his other tract, “Al-Iqtisad fi al-I’tiqad” [The Median In Belief], he indicted Islamic rationalists (spec. the Mutazila school of thought) while arguing for a strict Ashari approach. ***

- In the “Mihak al-Nazar fi al-Mantiq” [Touchstone Of Insight Into Logic], he passes his own pseudo-logic off as the only TRUE logic. Does this offer ANY penetrating insight into the study of logic? This question can be answered by posing another: When teaching logic, is this book used in ANY curriculum on the planet? ****

These were works of religious apologetics; nothing more. Rather than anything that resembled critical analysis, such material was a splurge in specious rhetoric. As a dyed-in-the-wool religionist, Al-Ghazali saw logic (that is, REASON) as something that infected Dar al-Islam—and, by implication, the entire world. For he—accurately, it might be noted—saw that independent (rational) thinking was causing people to lose their “iman”. In fact, the one thing he got right was that science and philosophy were the enemies of religious Faith. (With more and more scientific understanding, the raft of glaring mistakes throughout the Koran became increasingly difficult to ignore—a matter I explore in “The Koran A Miracle?”)

Al-Ghazali (correctly) recognized that lots of independent thinking amongst the rabble was a dire threat to the institutionalized dogmatism that he so ardently espoused. He concluded that we should therefore never avail ourselves of our critical faculties. EVER. Instead, we should all simply memorize what we’ve been instructed to memorize; and leave it at that. After all, his great epiphany was that true knowledge came not from critical inquiry, but from MEMORIZATION (of approved material). This point is often made via a silly tale about a bandit stealing his notes, then chastising him for not having memorized everything he’d written down. (Stealing his NOTES was equated with stealing his KNOWLEDGE.) A surefire sign that one does NOT have a profound grasp of material is that one has opted to memorize it by rote. Rote thinking is inimical to critical analysis. (More often than not, memorization is a colossal waste of time.)

To be fair, Al-Ghazali expressed some reservations about “taqlid” (received wisdom); but, of course, that is precisely what he promoted—though on his own terms. His bone to pick was with CERTAIN KINDS of “taqlid”. So long as one stringently adhered to the doctrines that HE propounded…well, then, everything was hunky-dory (ref. his “Al-Qistas al-Mustaqim”). Naturally, Al-Ghazali’s concern was that supplicants would listen to the wrong sorts of people. (His compunction, then, wasn’t with conformity per se; it was with conformity to the wrong sorts of things.)

It might also be noted that Al-Ghazali’s views were based on a delusive reading of the Koran, as explicated in his “Jawahir al-Qur’an” [Jewels Of The Koran]. This explains such works as “Al-Qislas al-Mustaqim” [The Just Retribution] (in which he tries the justify the retributive justice meted out by the Koran’s protagonist) and the “Mizan al-Amal” [Balance Of Action] (in which he presents the criteria for the rightness / wrongness of any given action). Here, “mizan” can be interpreted here as “standard of measure”. Unsurprisingly, this “balance” was simply a matter of hewing to Islamic doctrine. In other words: No balance at all.

It’s worth posing the question: Did Al-Ghazali have a firm grasp on the object of his scorn (science and philosophy)? A striking occurrence gives us the answer. In May of 2021, Hamza Yusuf did a seven-part series in praise of Al-Ghazali. In the entirety of the ten-plus hours of “The Jewels Of The Qur’an”, he was unable to mention a single worthwhile insight from the famed mujaddid. This is quite remarkable. Given a platform to showcase ANYTHING that may have been laudable, the president of Zaytuna College come up empty handed.

Al-Ghazali was many things; a fount of wisdom he was not. Al-Ghazali is most accurately characterized as a revivalist. Delusive thinking cannot abide in the midst of robust, critical thinking; so he dedicated himself to quashing the latter in order to bolster the former. There is a reason that Al-Ghazali’s “Maqasid al-Falasifah” [The Goals of the Philosophers] does not appear on a syllabus in any philosophy class at any accredited institution in the world. His understanding of philosophy was, at best, worthless.

Far from a reformer (one who seeks to move things forward), Al-Ghazali was a fundamentalist (one who seeks to bring things back to the fundamentals). He is a reminder that those who are most celebrated in Islam tend to be the Reactionaries.

{* The scathing epithet, “munafiq” is typically translated as “hypocrite”. It refers to one who professes to be righteous yet does not sufficiently hew to the Sunnah. “Mumin” simply means “believer”.}

{** “Ihya” means “revival [of]”. “Ulum” is a variation on the term for knowledge: “ilm”. The meaning of “din” is “way of life”. This has religious connotations; so the word is typically translated as “religion” or “Faith”—as is the case with Al-Ghazali’s “Kitab al-Arba’in fi Usul ad-Din” (rendered “Book of The Forty Fundamentals Of The Faith” in English). When it comes to Islam, religion IS a way of life. The Sunnah is meant to address EVERYTHING—from how one should eat meals to how political systems are to be designed. A brief, easily-accessible distillation of the larger work (which was composed in medieval Arabic) is Al-Ghazali’s most popular book: the oddly-titled “Kimiya-yi Sa’adat” (Alchemy of Happiness), which—interestingly enough—was composed in Middle Persian. The latter covers four basic topics: “ebadat” (religious duties), “mu’amalat” (dealings with other people), “monjiat” (salvation), and “mohlekat” (damnation). In it, there is no material whatsoever that could be accurately described as “philosophical”.}

{*** It’s worth noting that his “Bughyah al-Murid fi Masa’il al-Tawhid” was inspired by the vehemently anti-Mutazila tract, “Kitab al-Tawhid” by the (Hanafi) Persian theologian, Abu Mansur al-Maturidi of Samarkand. Speculation—whether about “batin” or anything else—was the perennial hobgoblin of Al-Ghazali’s career. He was more in his element when he stuck to cut-and-dried juridical matters (“usul al-fiqh”). After all, he was, at heart, an Islamic jurist (“faqih”). Hence works like the “Asas al-Qiyas”, the “Shifa al-Ghalil fi al-Qiyas wa al-Ta’lil”, and “Al-Mankhul fi Ta’liqat al-Usul”.}

{**** “Nazar” indicates something having to do with vision. Suffice to say, there was little ACTUAL “nazar” in Al-Ghazali’s book. If we were to survey all the great minds that have made significant contributions to our understanding of logic, we might ask if Al-Ghazali’s material played any role. Did Gottfried von Leibniz cite “Mihak al-Nazar fi al-Mantiq” in any of his writing? How about Gottlob Frege or Bertrand Russell or Rudolf Carnap or John von Neumann? How about ANY scholar, ANYWHERE at ANY TIME, who has specialized in this field? If we were to suppose, for a moment, that Al-Ghazali offered indispensable ideas, we might wonder why no luminary in the field has ever mentioned him. This abstention has nothing to do with him having hailed from Dar al-Islam. After all, Ibn Sina (“Avicenna”) enjoys near universal praise amongst intellectuals the world over.}