America’s National Origin Myth

September 10, 2019 Category: American Culture

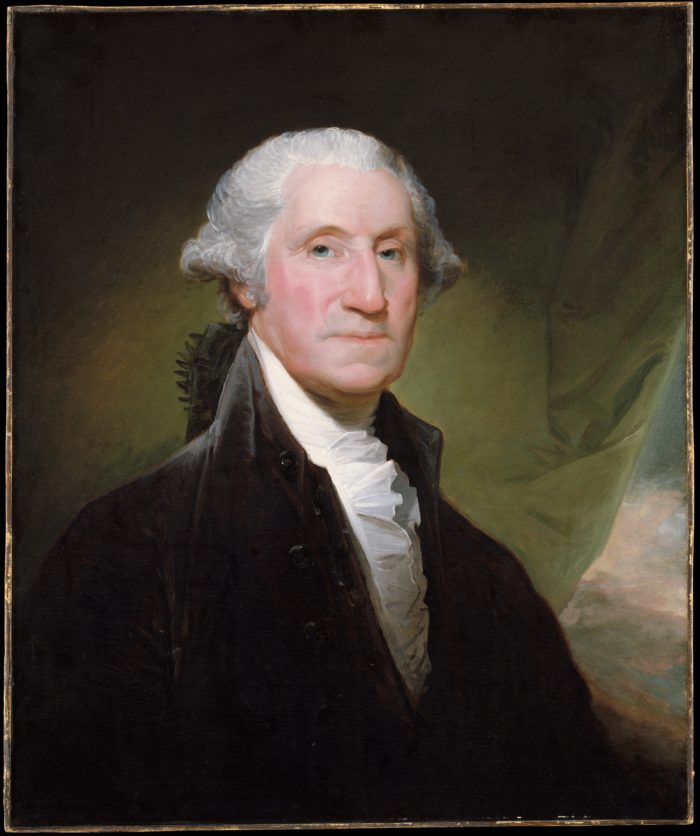

George Washington:

As colonel during the pre-Revolutionary years, Washington once averred: “Providence has directed my steps and shielded me.” When Benjamin Franklin once quipped that “god governs the affairs of men”, he was simply speaking in the argot of Providence. And when “In God We Trust” was first added to coins in 1864, it was likely intended as a way to galvanize the union–and, of course, invoke Providence–in the heat of the Civil War. When the (semiotically-charged) motto was inserted into the pledge of allegiance during the Eisenhower administration, it was not carrying out a legacy that went back to the nation’s founding. Rather, it was a way of asserting a stark geopolitical contradistinction: emphasizing the contrast between the (purported) forces of democracy and a (purportedly) godless Soviet “communism”.

Alas. It has come to pass that false impressions stem–in part–from people misconstruing idiomatic expressions as, well, something other than idiomatic. What it heaven’s name is going on here? (!) As we’ve seen, it was only natural that, during the Founding era, men of letters expressed themselves in the prevailing idiom of the time.

But the question remains: What were they REALLY getting at? George Washington provides us with a great illustration. Washington was especially fond of the locutions mentioned above (“the Creator”; “the Almighty”; “God”; etc.); and he invoked them with alacrity. Such grandiose oratory is sometimes referred to as “ceremonial Deism”. If Washington mentioned the Almighty in a public address, as he occasionally did, he was careful to refer to him not as “god” but with some non-denominational moniker like the “Great Author” or the “Almighty” or the “Creator”—a vague, Deist descriptor that had no theological baggage, nor any doctrinal connotations.

It is folly to interpret the use of such rhetorical flourishes as evidence for doctrinal fidelity or religious zeal; let alone to construe it as a sign of fealty to a specific INSTITUTION. In fact, even as he made use of such language, Washington was extremely wary of religion making incursions into politics. Just after being sworn in as the first president, he stated that “no one would be more zealous than myself to establish effectual barriers against the horrors of spiritual tyranny.” {6} In expressing this sentiment, Washington’s aim was simply to warn his fellow Americans against “religious persecution” (as he put it). His talk of barriers echoed Jefferson’s well-known use of the metaphor, “wall of separation” from three years earlier…and portended Madison’s stipulation of “the total separation of the church from the state” thirty years later.

It might be noted that this principle goes back to Tacitus’ declamation: “deorum injuriae diis curae”: leave offenses against the gods to the care of the gods. In other words, the concerns of religion are not to be treated as matters of State. This was echoed with Jesus’ admonition (in the Gospel of Matthew) to leave unto Caesar that which is Caesars; and leave unto god that which is god’s.

Washington believed that morality, not piety, was the ultimate standard by which good citizenship was determined. To reiterate: In his first speech as president, he stated: “The foundation of our national policy is laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality.” He clearly did not mean that the nation’s founding principles derived from the edicts of the Abrahamic deity (or were in any way validated by divine command theory). Instead, Washington made clear that the principles that he espoused came from the moral compass with which we are all endowed. As with Aristotle in ancient Athens, Washington tied virtue (esp. civic duty) with happiness. {5} He asserted that the “indissoluble union” between virtue and happiness stemmed from the “course of nature”. He could just as well have said that said union stemmed from “Nature’s God”; as that would have meant the same thing. {12}

Washington also noted that “religious controversies are always more productive of acrimony and irreconcilable hatreds than [disputes] which spring from any other cause.” To mitigate such controversies, Washington ordered all commanders of the Continental Army to “protect and support the free exercise…and undisturbed enjoyment of…religious matters.”

Like Benjamin Franklin, Washington’s reason for attending church services was to be involved in the community. For both Washington and Franklin, the concern was the communal, not the doctrinal. While they articulated themselves in the idiom of “god”, their approach to Faith was not dogmatic. As with virtually everyone else, he often used locutions like “thank god”, “god knows”, and “for god’s sake”; and, during the Revolutionary War, purportedly appealed for “the blessings of heaven” on the army (while having Thomas Paine read aloud his secular benediction). Never once, in his storied career, did Washington ever mention Jesus / Christ. (!) If he’d been Christian, this moniker would have eventually been used at some point—at least in passing.

We might also consider the pastors from Philadelphia who knew Washington best: James B. Abercrombie (Episcopal), Bishop William White (Episcopal), and Ashbel “Asa” Green (Presbyterian). All three made quite clear that they did not consider him a Christian. {16}

Granted, Washington seems to have been involved in FreeMasonry—a cult that was vaguely Abrahamic in some respects. (In some of his letters, he referred to the “Great Architect of the Universe”, a common Masonic moniker that had palpably Deistic undertones. He used other Masonic phrasing—as when he stated that the new nation “was under the special agency of Providence.”) When writing to fellow Mason, the Marquis de Lafayette, Washington refers to things in distinctly Masonic terms, specifying that he often “indulged” Christians. Clearly, he did not think of himself as a Christian. He was merely using the same phraseology that we encounter with other avowed Deists—from Voltaire and Montesquieu to Paine and Jefferson. All of them believed that a degree of religiosity had some practical virtues (i.e. maintaining civility in day-to-day affairs, encouraging temperance and forbearance, etc.)

In a letter written in February 1800 (about two months after Washington’s passing), Jefferson wrote in his personal journal: “Dr. [Benjamin] Rush told me (he had it from Asa [Ashbel] Green) that when the clergy addressed General Washington on his departure from government, it was observed in their consultation that he had never, on any occasion, said a word to the public which showed a belief in the Christian religion… I know that Gouverneur Morris [drafter of the U.S. Constitution] …has often told me that General Washington believed no more in [Christianity] than he did.”

It is telling that Washington refused to take communion when he attended church. When he was compelled by the clergy of Philadelphia to make a public confession of Jesus Christ, he refused to do so (see “The Writings of Thomas Jefferson” vol. I; p. 284). And he adamantly rejected the presence of clergy when he was on his death bed.