America’s National Origin Myth

September 10, 2019 Category: American Culture

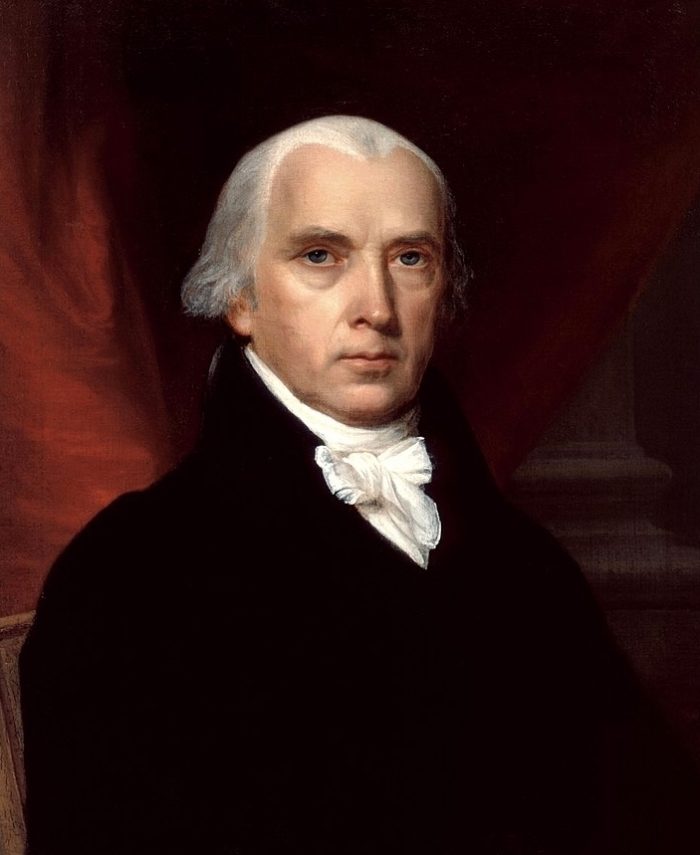

James Madison:

During the founding era, never was Christology tied into these judiciously-employed rhetorical flourishes. In a statement repudiating the desire–held by certain Christians at the time–for “an establishment of a particular form of Christianity through the United States”, Jefferson stated in a letter to Benjamin Rush: “I have sworn upon the alter of god eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” He recognized that any effort to base the governance of the nation on a particular religion entails a tyranny over the minds of its citizens. (That is: A theocratic regime borne of unbridled religionism was synonymous with despotism.) This declamation is all the more poignant because he conveyed his adamance by swearing “upon the alter of god” (like, say, swearing “on my mother’s grave”).

As if the point were not clear enough, in a letter to Major John Cartwright, Jefferson said of the (unfounded) notion that “Christianity is part of the common law” that “the proof TO THE CONTRARY…is incontrovertible.” He decisively denounced such a notion as “a conspiracy…between Church and State” that was being perpetrated by perfidious “rogues”. In sum: Jefferson’s ideals were diametrically opposed to even the slightest hint of Christian theocracy. Religiosity (in the doctrinal sense) could only ever undermine the integrity of deliberative democracy. The scourge of institutionalized dogmatism was antithetical to a vibrant demos.

James Madison echoed this sentiment when he said: “Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind; and un-fits it for every noble enterprise, every expanded prospect” (letter to William Bradford, April 1,1774). And in a letter dated 1822, Madison wrote: “Every new and successful example of a perfect separation between ecclesiastical and civil matters is of importance. And I have no doubt that every new example will succeed, as every past one has done, in showing that religion and government will both exist in greater purity the less they are mixed together.”

For Madison, it was quite clear that there must a wall separating religion from governance; and vice versa (as is the case with walls). Keeping the State out of religion entails keeping religion out of the State.

Madison recognized that doctrinal thinking was inimical to deliberative democracy. In a letter to F.L. Schaeffer (Dec 3, 1821), he stated: “The experience of the United States is a happy disproof of the error so long rooted in the unenlightened minds of well-meaning Christians, as well as in the corrupt hearts of persecuting usurpers: That without a legal incorporation of religious and civil polity, neither could be supported. A mutual independence is found most friendly to practical religion, to social harmony, and to political prosperity.”

In the eighty-five essays that make up The Federalist anthology, “god” occurs only twice—both times by Madison, who used the word in a Deistic sense. (Gore Vidal aptly noted the word was used in the “only Heaven knows” sense.) The prospect of religious groups vying for supremacy would have terrified him. Madison knew that an overly-fragmented polis—whereby the political process was governed by partisan hacks engaged in a game of one-ups-man-ship—was inimical to the democratic process.

In Federalist 10, Madison implicitly conceded that deliberative democracy is predicated on the ability of the polity to transcend partisanship; which, ironically, is why he was somewhat SYMPATHETIC to factions. (His take was that so long as the rank and file remained fragmented, it would not be equipped to pose any threat to the properties classes.) He recognized the innate human proclivity toward “faction”—by which he meant our tendency to divide ourselves into political tribes that are so inflamed with “mutual animosity” that they are “much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to cooperate for their common good.” This leads to a public square in which “the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts.”

Bottom line: A fractured demos—that is: a polity that was riven with quibbling factions jockeying for power—made deliberative democracy untenable; as it kept the demos perpetually distracted. (Social media has only exacerbated the fragmentation of the demos; partitioning us into dialectical silos. Religious fixations have also contributed to the division in U.S. politics.) Madison believed that “religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind; and unfits it for every noble enterprise.” Clearly, religiosity was NOT a boon to deliberative democracy.

Along with Jefferson, Madison recognized that in a genuine democracy, there could be no theocratic element whatsoever. After all, the point of democracy was for the State to remain categorically neutral on religious (read: personal) matters. The upshot of this was neither to advance nor to inhibit religious practice. So long as it in no way placed a burden on bystanders, practicing one’s own religion of one’s own accord needn’t be opposed to civic-minded-ness. (On your own time, on your own dime.)

Again, we see that the assurance of personal prerogative–for EVERYONE–is the essence of individual liberty. Madison’s stance on the STATE’S freedom from religion could not have been clearer: “If religion be not within cognizance of Civil Government, how can its legal establishment be said to be necessary to Civil Government?” How indeed. Religion, Madison recognized, is NOT the basis for (“within the cognizance of”) the maintenance of civil society.

Hence Madison’s advocacy for a wall of separation–harking back to Roger Williams’ aforementioned insight from the 1630’s. He recognized that when that wall is breached, democracy suffers: “What influence–in fact–have ecclesiastical establishments had on Civil Society? In some instances they have been seen to erect a spiritual tyranny on the ruins of Civil authority; in many instances they have seen the upholding of the thrones of political tyranny; in no instance have they been seen the guardians of the liberty of the people.” He noted elsewhere “a strong bias towards the old error”: the erroneous conception that “without some sort of alliance or coalition between government and religion neither can be duly supported.” He concluded: “An alliance or coalition between government and religion cannot be too carefully guarded against… [Therefore] every new and successful example of a PERFECT SEPARATION between ecclesiastical and civil matters is of importance” (letter to Edward Livingston, Jr.; 1822).

In a letter to Baptist Churches in North Carolina (June 3, 1811), Madison put it more bluntly: “Having always regarded the practical distinction between Religion and Civil Government as essential to the purity of both, and as guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States, I could not have otherwise discharged my duty on the occasion which presented itself.”

Madison also did not mince words when it came to the deleterious effects of institutionalized dogmatism. He spoke of the “almost fifteen centuries” during which Christianity had been on trial: “What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry, and persecution.”

It makes sense, then, that two years prior to the Declaration of Independence (January of 1774), in a letter to William Bradford, Jr., Madison wrote: “Ecclesiastical establishments tend to great ignorance and corruption, all of which facilitate the execution of mischievous projects.” As if that weren’t enough, Madison saw fit to conclude with a plaintive observation: “Rulers who wish to subvert the public liberty have found an established clergy convenient auxiliaries.” Meanwhile: “A just government, instituted to secure and perpetuate [liberty], needs them not.” Clerics did not comport with deliberative democracy.

Madison echoed Thomas Jefferson’s proclamation of a wall of separation between religious observance and the business of the federal government–stating in 1819: “The civil government operates with complete success by the total separation of the church from the State.” In other words, democracy abides insofar as this wall of separation is maintained. He reiterated that the U.S. Constitution forbade ANYTHING like the establishment of a “national religion”. As President, Madison elaborated on the matter:

“What influence, in fact, have ecclesiastical establishments had on society? In some instances they have been seen to erect a spiritual tyranny on the ruins of the civil authority; on many instances they have been seen upholding the thrones of political tyranny; in no instance have they been the guardians of the liberties of the people. Rulers who wish to subvert the public liberty may have found an established clergy convenient auxiliaries. A just government, instituted to secure and perpetuate it, needs them not.” He continued: “The religion, then, of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man: and that it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate.”

Madison concluded thus: “During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What has been its fruits? More or less, in all places, pride and indolence in the clergy; ignorance and servility in the laity; in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution” (A Memorial and Remonstrance; addressed to the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1785).

Later, in a Boston address in 1819, Madison noted that “the morality of the priesthood, and the devotion of the people have been manifestly increased by the TOTAL SEPARATION OF THE CHURCH FROM THE STATE.”

What of the U.S. being founded on the principles of “capitalism”? James Madison once referenced the corruption of his time, whereby “stock jobbers” (i.e. those engaged in rent-seeking; as well as the more odious forms of financial speculation) were known to collude with lackeys in the federal government. He noted that the impresarios of big business pulled the strings of those in public office; thereby undermining the popular will. The avarice of a well-positioned few, not a sincere concern for the commonweal, was the primary motivating factor.

Madison thus expressed his compunctions with capitalism-run-amok (what came to be known as corporatism); which was unconcerned with the common good. Even in the first decades of the new Republic, public policy was often held hostage by moneyed interests; and had only a tenuous relation to the public interest. Such anti-democratic machinations were later made famous by the back-room deal-making in Tammany Hall, and continue to the present day with the corporate lobbyists on K Street.

Madison foresaw the depredations of corporatism, wherein legislation was bought and sold to the highest bidder. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson (dated August 8, 1791), he confessed that “my imagination will not set bounds to the daring depravity of the times; as the stock jobbers will become the pretorian band of the government; at once its tools and its tyrant; bribed by its largesses; and overwhelming it by clamors and combinations.” The call to get money out of politics would have been endorsed not only by Madison, but by Jefferson as well. An agrarian at heart, Jefferson championed distributed power; and was well aware of the perils of concentrated wealth / power—especially plutocracy (the collusion of financial and political power). {18}

When we look to the principles on which the U.S. was founded, we find that they often do not accord with what we now know as the “Washington Consensus”. We’ve already seen how Neo-liberal support for corporatism is antithetical to early conceptions of the Republic. This was illustrated by Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that what is important in a democracy is that “those who govern do not have interests contrary to the mass of the governed; for in that case [their] virtues could become almost useless and [their] talents fatal.” {20}

In sum: A genuinely democratic government is a meta-religious institution, exercising even-handedness toward all Faiths…as well as toward a complete lack thereof. Such a (secular) State serves to minimize the negative effects of religious discord in civil society; not to mention its tendency to sabotage deliberative democracy. Just as importantly, it mitigates religion’s disruptive effects on democratic governance. Madison was well aware that importing religion into civic affairs was a recipe for disaster.