America’s National Origin Myth

September 10, 2019 Category: American Culture

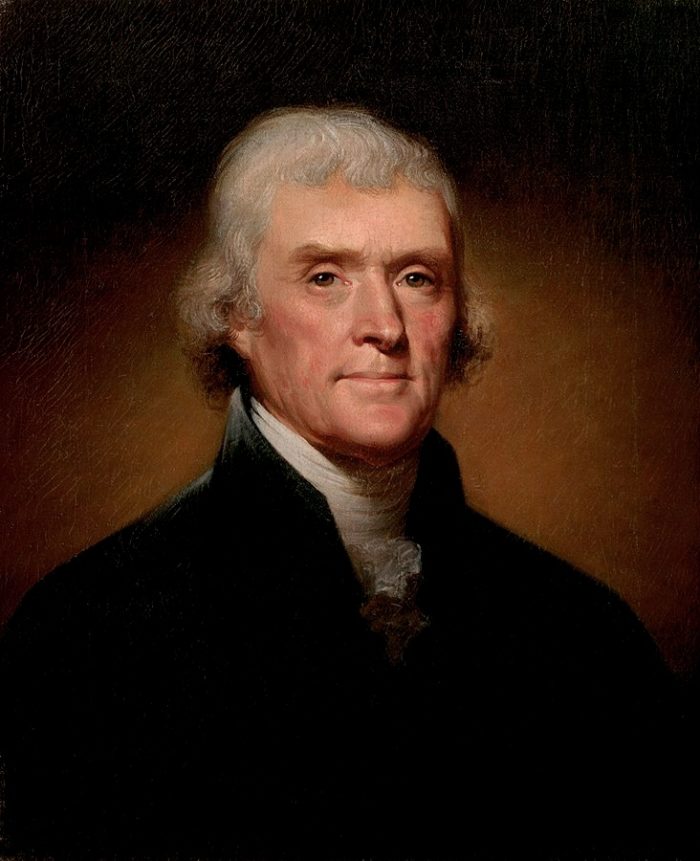

Thomas Jefferson:

What of Adams’ political rival, Thomas Jefferson? A frequent attendee of the local Anglican (i.e. Episcopalian) church who openly denied the divinity of Jesus, Jefferson was surprisingly frank about his suspicions of institutionalized dogmatism; and so was careful to avoid leaving the impression that any of the ideals he espoused were in any way grounded in doctrinal thinking. It was not for nothing that he was viciously pilloried for being a de facto atheist by his political opponents, for whom his reticence to identify as a Christian was seen as problematic.

When he drafted “A Summery View Of The Rights Of America” in 1774, Jefferson opted to quote Cicero rather than the Bible. For it was Cicero’s disquisition, not Christian scripture, that made the case for civil rights. In Jefferson’s telling, those rights were deemed “god-given” (as was the colonialists’ liberty and dignity). This was the standard conviction of a Deist. Indeed, such things could be said to have been “god-given” just as were the leopard’s spots and the zebra’s stripes and blueness of the sky.

In putting forth his case, Jefferson asserted recourse to the laws of “nature and of nature’s god”; not of the Biblical god. Just as with John Locke before him, he spoke of “natural rights” (as with, say, the freedom of conscience), which were not derived from any catechism; they could be gleaned from the natural order of things. Again: This was an echo of Renaissance Humanism. Consequently, Jefferson invoked “a decent respect for the opinions of mankind”, not for the revelation of prophets. MORALITY was the sine qua non; not religiosity.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Jefferson proudly asserted: “If ever the morals of a People could be made the basis of their own government, it is our case.” The basis for government, that is, did not proceed from divine commandments, but from our own moral faculties. Again, the appeal was to our innate moral compass, not to the diktats of this or that scripture.

In fact, the inalienable rights Jefferson enumerated could not be found anywhere in the sacred texts he had on his library. Rather, they were to be found in the exposition of Locke and Montesquieu. Jefferson had a strong case to make about democratic principles; and–most would agree–he made it as eloquently as possible. Religion had nothing to do with it. {9}

In assaying his choice of wording, we might bear in mind that Jefferson was especially known for poetic stylization–as were both Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin. (Such florid rhetoric might be contrasted to the more dry, turgid prose of the Federalist Papers.) It should come as little surprise, then, that Jefferson made use of the prevailing idiom of the time.

The point here is worth reiterating: When idiomatic expression is used to convey an idea in a maximally poignant way–as savvy writers tend to do–the astute reader is able to abstract the underlying message from the particular phraseology employed. {10} So it stands to reason that Jefferson–with the approval of Ben Franklin–opted to use the locution, “Nature’s God” in the opening statement of his letter to King George III of England in 1776, whereby he declared independence of the American colonies from the crown. After all, such an invocation was prudent when seeking to articulate one’s intentions to a royal cynosure who thought ENTIRELY in Providential terms.

Providence was, after all, part of the zeitgeist. This is why Jefferson CONCLUDED the letter to the British monarch with an invocation of “Providence”, intimating a divine imprimatur for the revolutionary cause (as people often did when employing soaring oratory). Such wording was designed to ensure maximal resonance with George III and his advisors. It had nothing whatsoever to do with Messianism.

Also in that propitious letter, Jefferson referred to “Nature’s God” as “Creator” when he posited the endowment of inalienable rights. Such wording was often used when discussing NATURAL RIGHTS in the tradition of John Locke. Deists did, after all, believe in a Creator; though no particular doctrinal points followed from that precept.

As a Deist, it was only natural for Jefferson to employ the genteel locutions of his era–as Deists often did. Along with the vehemently anti-religious Thomas Paine, Jefferson invoked “Nature’s God”…which, he was careful to point out, correlated with “the natural rights of mankind”. None of this had anything to do with any particular sacred doctrine. To ensure this was clear, the common locution “we hold these truths to be sacred”–with its theological connotations–was changed to the more naturalistic “we hold these truths to be self-evident”. After all, the idea was to appeal to REASON, not to divine ordinance.

This point is crucial to understanding how and why the “Founding Fathers” articulated themselves as they did. When Jefferson employed the Lockean locution, “Nature’s God” in his letter to king George III, he was speaking the language of the Enlightenment–a language embraced by non-religionists like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Henry Saint John of Bolingbroke. The phrase was standard in the argot of “natural law theory”, of which Jefferson was an aficionado.

In fact, considering his familiarity with Locke, it would have been surprising had he NOT used the phrase “nature’s god”. What he did NOT say was “the god of Abraham” or “the Christian god”. For–clearly–he did not have in mind the god of one or another CHURCH. This is evidenced by the fact the some of the more religious signatories to the Declaration of Independence PROTESTED such phrasing, as they deemed it sacrilegious. They were–after all–well aware that “nature’s god” had nothing whatsoever to do with their creed. (!) It was commonly understood to be non-religious terminology.

That George III–a pious man–was considered head of the Church of England meant that Jefferson was obliged to speak his language. And so he did. Thus it was a RHETORICAL strategy to phrase things in a way to which the target audience (the British monarchy) could relate. Hence Jefferson spoke of “divine providence”, and articulated things accordingly. We might bear in mind that kings / queens of England were convinced that they ruled according to divine right; so–in seeking to convey a point as poignantly as possible–Jefferson would have been remiss NOT to couch things in providential terms.

And so it went: Jefferson was–effectively–a Deist; though he eschewed that particular label, as he associated it with Judaic theology, which he saw as derelict. Tellingly, he opted to use “Nature’s God”, which was a patently Deist locution; as it was held in contra-distinction to SCRIPTURE’S god, which was supernatural and interventionist. To reiterate: Jefferson was no oddity. His contemporary mentors were all Deists–most notably: Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Henry Saint John of Bolingbroke.

In keeping with the rest of his writing, Jefferson’s tactful use of certain turns-of-phrase was largely about waxing poetic. It was only natural, then, that he included such rhetorical flourishes in this propitious letter. Obviously, such phrasing went far beyond mere colloquialisms like “Oh, my god!” The loaded wording Jefferson employed was intended to hit a nerve; and it a nerve it did. By using such super-charged locutions, there were surely connotations that would have struck a chord with the British. It should go without saying that the letter resonated with its intended audience not only because of WHAT it said, but HOW it said it.

For Jefferson, religiosity was a matter of personal prerogative. In his 1784 “Notes On Virginia”, Jefferson wrote: “The legitimate powers of government extend only to such acts as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” He recognized that a person’s freedom OF (his own) religion entailed that person’s freedom FROM (the next guy’s) religion. One freedom is, indeed, the logical corollary of the other. (In other words: One cannot have freedom OF one’s own religion without a guaranteed of freedom FROM another’s religion.) I am not infringing upon your liberties when I prevent you from infringing on my own liberties.

The matter here, then, is simply one of omni-symmetrical liberty: Freedom OF the exercise of one’s own Faith entails freedom FROM others’ exercise of their Faith. MY practice of religion must in no way encumber anyone else’s ability to do the same. For any given party, the rule of thumb amounts to: On your own time, on your own dime. {11}

Such boundary conditions are required for maintaining a condition of omni-symmetry with respect to personal prerogative. Any given person’s freedom to exercise his own Faith stops the moment it places a burden on any bystander. To recapitulate: A corollary of freedom OF religion is freedom FROM religion. One can’t have the former without the latter.

This means that genuine religious liberty cannot exist without a patently secular (read: religiously neutral) government. Protection of one person’s religious prerogative requires protection from mandates by any and all other religions. One person’s exercise of religion cannot ever be allowed to inhibit or constrain–in any way whatsoever–the next person’s ability to exercise his own religion (or, for that matter, to simply refrain from exercising ANY religion).

This means no religious favoritism on the part of the State. But for Christians who’d much prefer to enjoy favor, the best way to countermand this precedent is to pretend that the American Republic was founded as a “Christian nation”; then begrudge anyone who doesn’t play along with this ruse.

Secularism entails something quite different, as the American Founders recognized. It is not within the jurisdiction of the government to enforce piety…in ANY form; nor is it the government’s place to curtail anyone to exercise piety of their own accord (so long as it in no way infringes on anyone else’s prerogative to do the same for himself). With this in mind, Jefferson drafted Virginia’s statute for religious freedom, wherein he explicated the principle of separation of church and state.

Jefferson was crystal clear on the matter: No person should be compelled to support any religious institution with taxes; nor compelled to subsidize any religious ministry–be it evangelism or worship. (One might call this the “on your own time, on your own dime” principle.) Jefferson’s primary rational for this position was an inviolable freedom of conscience (couched in terms of an endowment by the Creator). The point wasn’t to propound this or that theological position; the point was to recognize the ENDOWMENT.

As a (purported) virtue, “religious” was used (by Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, Madison, et. al.) in the non-dogmatic sense. The key was to always treat Faith as a personal affair, never as public policy. The vision was of a polity in which each citizen participated in any given religion of his/her own accord. (I won’t burden you with my religion; you don’t burden me with yours. And we can both go about our business.)

When Thomas Jefferson drafted the Virginia statute for religious freedom in 1777, he characterized the document as having “within the mantle of its protection the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mohametan, the Hindoo and Infidel of every denomination.” For Jefferson, this landmark charter was not an enjoinder for theocracy; it was a mandate for personal prerogative. (The statute would serve as the basis for the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution twelve years later.)

Jefferson’s view on this matter was perfectly in keeping with the thinking at the time, which was loud and clear. He went so far as to cite John Locke, who—in 1689—submitted that “the church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the commonwealth [the political realm].” It was based on this “separation” that Jefferson proposed that Virginia CURTAIL all tax support for religious activity—recognizing the natural right of all people to practice their Faith of their own accord. (He honored the maxim: On your own time, on your own dime.) It’s worth recalling Jefferson’s adage that “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

His Virginia “Statute For Religious Freedom” set the precedent for the separation of church and state. {22} When it was passed by the Virginia legislature in 1786, Jefferson rejoiced that there was finally “freedom for the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and the Mohammedan, the Hindu and infidel of every denomination.” First composed in 1779, it read: “No man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burdened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.”

Historian, Joseph Ellis noted that “If [Jefferson] had been completely scrupulous, he would have described himself as a Deist who admired the ethical teachings of Jesus as a man rather than as the son of God. (In modern-day parlance, he was a secular humanist.)” Jefferson’s pride and joy, the University of Virginia, was notable among early-American seats of higher education in that it had no religious affiliation whatsoever. Jefferson even banned the teaching of theology at the school. He hoped for a day when religious dogmatism would be a thing of the past. “The day will come,” he predicted (wrongly, so far), “When the mystical generation of Jesus—by the supreme being as his father, in the womb of a virgin—will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the [mind] of Jupiter.” In keeping with this, we shouldn’t be surprised that he dismissed the Book of Revelation as “the ravings of a maniac”.

So what did Jefferson think of Christian doctrine PER SE (to wit: repentance; salvation via belief in Christ, etc.) In a letter to William Short (dated 1820), he wrote that “it is NOT to be understood that I am with [Jesus] in all his doctrines. I am a Materialist. He takes the side of Spiritualism; he preaches the efficacy of repentance toward forgiveness of sin. I require a counterpoise of good works to redeem it.” In fact, Jefferson’s thinking was heavily influenced by Cicero—the loadstar of Stoicism.

Virginia’s Statute For Religious Freedom was ratified by the state’s General Assembly in 1786, three years before the Constitutional Convention; and so would serve as precedent thereafter. In the parlance of the Founders, “religious freedom” was not about imposing one’s creed on others; it was about freedom of conscience…so long as it put no obligation / restriction on one’s neighbor. In other words: “To each his own.” It is folly to construe this as an exhortation to be “religious” in the (dogmatic, tribalistic) sense we often use it today. The notion of a certain party’s creed being used as the basis for public policy would have struck the Founders as perfidious.

Revealingly, Jefferson was sometimes strikingly straight-forward about his disdain for religious dogmatism. He once wrote to John Adams: “The day will come when the mystical generation of Jesus by the Supreme Being in the womb of a virgin will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the brain of Jupiter.” Scorned by devout Christians at the time (who derided him as an “atheist”, just as they did with Paine), Jefferson never budged when it came to his unorthodox views of Faith; and never wavered on his anti-theocratic stance. (Thomas Paine, another Deist who held religion in abeyance, was also inaccurately derided as an atheist. In reality, nobody embodied the ideals of the American Revolution more than Paine.)

When he bowdlerized the New Testament, Jefferson compared removing all the passages involving dogmatic nonsense–and accounts of the supernatural–to “extracting diamonds from a dunghill.” Hence his “The Life And Morals Of Jesus Of Nazareth”. So what, exactly, DID Jefferson cull from the Gospels after this extensive textual pruning? In treating the source-material as an allegory rather than as a chronicle, he highlighted the moral messages that were conveyed–thus abstracting from the Christological hocus-pocus in which it had been embedded. Jefferson was astute enough to recognize the DIDACTIC value of scripture; no dogmatism required, nothing supernatural involved. In other words: The moral messages could be divorced from all the soteriological musings.

As with his fellow Founders, Thomas Jefferson saw religiosity as a private affair. Consequently, so far as he was concerned, the separation of church and state was paramount. This was made clear when Virginia’s statute for religious freedom was made law. Later that same year (1786), in a letter protesting a proposed “general assessment” in Virginia (a move to levy taxes to fund certain religious activities), Jefferson expounded:

“[T]he impious presumption of legislators and rulers, civil as well as ecclesiastical, who, being themselves but fallible and uninspired men, have assumed dominion over the faith of others, setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and infallible, and as such endeavoring to impose them on others, hath established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world, and through all time; that to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves, is sinful and tyrannical.” In sum: Any move to use public funds to subsidize the promotion of religion was antithetical to democracy.

In the same letter, Jefferson was careful to point out that “our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions.” That is to say: participatory democracy does not depend on religiosity. Quite the contrary: Democracy is predicated on a clearly-demarcated boundary separating matters of Faith from matters of civic life. This is precisely why Jefferson saw fit—in a letter to Baptist leaders in Connecticut on New Year’s day, 1802—to make it crystal clear that there must be an un-breach-able “wall of separation” between the State and any church. His point: The State should no more meddle in a congregation’s affairs than the followers of a certain doctrine should meddle in the affairs of the State. The Christians in Danbury wholeheartedly concurred. (!)

Was this position inimical to the Founders’ vision? Of course not. Jefferson even went so far as to claim that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is what BUILT this wall of separation; and pointed out that this was perfectly in keeping with “natural rights”…which were themselves consummate with civic responsibility (“social duties”, as he put it). Jefferson concluded the letter by reciprocating the congregation’s “kind prayers for the protection and blessing of the common Father and Creator of man.” Why phrase it that way? Well, why not?

In his letter to the Danbury Baptists, Jefferson clearly saw the 1st Amendment as “building a wall of separation between church and state.” {19} For most, this was interpreted as an integral part of the intent of the Amendment—a fact that was affirmed by Reynolds v. United States in 1878. Jefferson saw religion as a personal matter “which lies solely between man and his god.” The prospect that anyone might have the audacity to use personal Faith as a justification for public policy was beyond the pale.

It is plain, then, that the 1st Amendment was an explicit repudiation of the Puritan mini-theocracy established in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the two centuries leading up to the American Revolution (not to mention the explicitly Catholic colony established in Mary-Land). The point of the Revolution—as envisioned by Thomas Paine—was to emancipate the people from religious control, not to alter the brand of that control. It was obvious to (almost) everyone involved that freedom OF religion meant freedom FROM religion. That is: To each his own. This entailed something quite straight-forward: No party’s exercise of Faith could in any way impost burdens / obligations on any other party.

Jefferson was adamant that religiosity and governance were to remain in their appropriate purviews. He saw how important it was that each mode of human activity be relegated to its own (delimited) domain. And that was perfectly fine for the Faithful. For Jefferson insisted that–in the end–the truth will out (that is, so long as free inquiry was allowed to run its course). In the same letter, he reminded his fellow Virginians that “truth is great and will prevail if left to herself, that she is the proper and sufficient antagonist to error.” He added that truth “has nothing to fear from the conflict, unless by human interposition disarmed of her natural weapons, free argument and debate–errors ceasing to be dangerous when it is permitted freely to contradict them.” In sum: Jefferson recognized that the only TRUE democracy was DELIBERATIVE democracy. Hewing to the edicts of ancient texts was NOT the basis for this process.

Critical thinking (that is: independent thought) always trumped the dogmatic tendencies of religion in its fundamentalist form. Jefferson was emphatic in a letter to Peter Carr in 1787: “Question with boldness the existence of god. Because if there be one, he must more approve of the homage to reason than that of blindfolded fear.” {10} It is indubitable that the author of the “Declaration of Independence” did not predicate his vision for the new Republic on religious doctrine…let alone prescribe doctrinal fealty as a condition for democracy.

One of the most fundamental elements of civil society is freedom of conscience. It was for this reason that–in his famous letter to the Danbury Baptist Association–Thomas Jefferson emphasized that “religion is at all times and places a matter between god and individuals.” {19} Public policy has no place in such affairs—just as such affairs have no place in public policy.

To reiterate: Thomas Jefferson was wary of the dogmatic tendencies of religionism. This was made especially clear when he wrote: “The caliber of people who serve [the Christian god]…are always of two classes: fools and hypocrites.” Elsewhere, he wrote: “Religions are all alike: founded upon fables and mythologies.” To top it all off, he conceded: “I do not find in orthodox Christianity one redeeming feature.”

Jefferson was also careful to point out that morality and doctrinal fealty often did not coincide; and that we conflate the two at our own peril. In a letter to Unitarian minister, Richard Price in October of 1788, he wrote: “There has been in almost all religions a melancholy separation of religion from morality.” For him, as for the other major Founders, morality trumped religiosity. And the glaring disjuncture between morality (as propounded by Jesus of Nazareth via parable) and the institution known as the Christian church was important to recognize.

In that same letter, Jefferson went on to list all the formal rituals of Roman Catholicism (“Popery” as he called it), including “getting to heaven by penances, bodily mortifications, pilgrimages, saying masses, believing mysterious doctrines, burning heretics, aggrandizing Priests”. He also rebuked Protestantism, what with its “fastings and sacraments” and other fatuous rigamarole. Regarding all those liturgical shenanigans, he then asked: “Would not society be better without such religions?”

Such pontification was no anomaly. In a letter to James Fishback in September of 1809, Jefferson noted the myriad sects “in their particular dogmas all differ, no two professing the same…[consisting as they do of different] vestments, ceremonies, physical opinions, and metaphysical speculations.” He pointed out that all this Tom-foolery–pompous and mawkish–existed independently of moral precepts (which are, he noted, what REALLY matter).

As he put it in a letter to Patrick Henry in October of 1776: “The care of every man’s soul belongs to himself. But what if he neglect the care of it? Well what if he neglect the care of his health or estate, which more nearly relate to the state? Will the magistrates make a law that he shall not be poor or sick? Laws provide against injury from others; but not from ourselves. God himself will not save men against their wills.” Thus freedom of conscience is paramount in a genuinely democratic society. Faith was a matter of personal prerogative, not public policy. Again: “On your own time, on your own dime.”

Jefferson left no doubt that dogmatism was inimical to deliberative democracy; and that religiosity was a personal affair. As if this point were not already clear enough, Jefferson once wrote: “I have always thought religion a concern purely between our god and our consciences, for which we were accountable to him and not to the priests. For it is in our lives, and not from our words, that our religion must be read. But this does not satisfy the priesthood. For they must have a declared assent to all their interested absurdities. My opinion is that there would never have been an infidel if there had never been a priest.” Then, in a letter to Thomas Law in June 1814, he stated that “our moral duties…are generally divided into duties to god and duties to man.” The former was a private spiritual matter; the latter was a public matter.

This distinction made perfect sense, as the Faith Jefferson espoused was categorically “natural” (in contradistinction to institutional). We might recall that “natural religion” was the sense of “religion” touted in David Hume’s “Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion”. This conceptualization was patently secular in nature (Hume was an atheist). {9} That is to say, “natural religion” was only “religion” in the sense of the (non-dogmatic) Faith espoused by Deists like Denis Diderot and Thomas Paine; and, later, by Johan von Goethe, John Stuart Mill, and William James. At the time, the most notable exemplar of “natural religion” was Immanuel Kant, who explicated how “religion” might exist “within the bounds of reason”; and in no way rested on dogmatism. {3}

Here’s the key: For Jefferson, “NATURAL religion” (as opposed to institutionalized religion) was synonymous with morality. For he recognized that religion QUA INSTITUTION (sectarian, dogmatic, and prone to clericalism) often led to dysfunction. This fundamental distinction has been espoused by all the great Deists of history–from Spinoza to Einstein.

Jefferson’s position should not come as a surprise. It was widely recognized at the time that sanctified dogmatism had often been the skein of civil society. To make the point clear, in June of 1822, the elderly statesman wrote in a letter to the reverend, Thomas Whittemore: “I have never permitted myself to mediate a specified creed. These formulas have been the bane and ruin of the Christian church, its own fatal invention which through so many ages made Christendom a slaughter house, and to this day divides it into [sects] of inextinguishable hatred of one another.”

Elsewhere, Jefferson averred: “I have examined all the known superstitions of the world; and I do not find in our particular superstition of Christianity one redeeming feature. They are all alike founded on fables and mythology.”

Jefferson evinced contempt for religion in the institutional sense even as he harbored respect for a liberalized notion of “religion” in the non-institutional sense. Faith was a private matter; and was only sullied when institutionalized. Other liberal thinkers would concur on this point–from William Sloane Coffin Jr. to Martin Luther King Jr. to Johan Rawls.

Governance, then, must never be at the mercy of religious doctrine. Jefferson was crystal clear on this point: “The legitimate power of civil government extends no further than to punish the man who does ill toward his neighbor.” In other words, it was not the government’s place to enforce any given group’s sacred doctrine, nor to enact policies designed to promote this or that religious dogma. The State’s sole role was to attend explicitly to jurisprudential matters in the SECULAR domain.

This conviction informed Jefferson’s view of the U.S. Constitution. Being as it is a historical artifact, made by man in all his fallibilities, no document is unimpeachable. Even the best national charters must evolve with society—taking into account new developments, new insights. The notion of a “living constitution” means that political systems are a work in progress. It is important to keep this in mind when referring back to a dated national charter—as all eventually become.

In a letter to Samuel Kercheval, Thomas Jefferson lamented that “some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched.” This, he recognized, was not a good thing. Democracy was an on-going experiment that was subject to modification as the need arose (as circumstances evolved; as new information came to light), so long as it adhered to its foundational principles. In sum: Democracy is a process, not a destination. {21}

In the letter, Jefferson went on to note that “laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths disclosed, and manners and opinions change with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times.” {23}

The principle of separation of church and state was first posited EXPLICITLY by the progressive pastor, Roger Williams (founder of Rhode Island) in the 1630’s. (For earlier instantiations of this tenet, see my essay on the history of legal codes.) Williams noted that no worthwhile religion seeks collusion with the State, let alone demands State support.

As we’ll see shortly, Benjamin Franklin also recognized this basic fact. Franklin stated: “When a religion is good, I conceive that it will support itself; and when it cannot support itself, and god does not take care to support it, so that its professors are obliged to seek the support of the civil power, it is a sign…of its being a bad one.”

Of course, leaving religion out of politics goes back to Jesus himself, who abjured to “leave unto Caesar that which is Caesar,” where the Roman Imperium represented the affairs of State. The point of democracy, of course, is that authority is accorded–and thus derives its legitimacy–from the bottom up; NOT from the top down. In other words: There is no imperium–theocratic or otherwise.

Along with Franklin, Jefferson recognized that keeping religion in its appropriate place poses no problems for a genuinely democratic society. Indeed, civil society is not a function of any particular theology. In his Bill For Religious Freedom, Jefferson articulated this position–even as he opted to use the familiar idiom, “Almighty God”. But WHAT OF this “Almighty God”? Jefferson is clear: “[He] hath created the mind free, and manifested his supreme will that free it shall remain.” How is this possible? Jefferson specified: “By making [each person’s mind] altogether insusceptible of restraint.” These are the words of a Deist, not of a religionist. {10}

Regarding Jefferson’s auspicious letter to King George III, it is difficult to take every word seriously AS IT WAS–considering the exigencies of the time. This is–after all–the same document that proclaims that “all men are created equal” even though it meant ONLY males, and did NOT mean anyone who wasn’t white. If all humans qua humans were truly endowed (by their Creator; a.k.a. “nature’s god”) with certain inalienable rights, then surely such an assertion encompassed women…and African Americans. (We’re ALL supposedly made in the image of god, are we not?) That “all men” actually entailed “only white, land-owning men” rather than “mankind” is rather disheartening; as Jefferson surely had “mankind” as his ideal. Alas, in practice, “The People” referred to landed gentry…even as it may have referred to all civilians IN PRINCIPLE.

The point here is that the phrasing of even the most vaunted historical documents must be taken with a rather hefty grain of salt; and the exposition’s deeper meaning considered in terms of its historical context. Surely, Jefferson was fully aware that the SPIRIT OF his letter was the thesis that all of mankind–rich and poor, male and female, black and white–was entitled to enfranchisement. Consequently, he would have conceded that the vision of the groundbreaking Declaration could not be fully realized at the time (the LITERAL reading of what he wrote notwithstanding). So for those who are hung up on the locution “our Creator”, it suffices to say that they are completely missing the point. To fixate on this as a tacit declaration of Christian fealty is to be heedless of how exposition works in the real world. In considering the underlying message that Jefferson was trying to convey, this locution is rather beside the point.

For us to now fixate on Jefferson’s use of “our Creator” in articulating his point is to miss the entire forest for a single fig-leaf. {4}

It should also be noted that whenever the buzz-term, “religion” / “religious” was used, it was typically coupled with “morality” / “moral”, as devout-ness was typically associated with self-discipline and noble character. {12} Common-folk could relate to such terms; so those were the terms savvy orators tended to use. Up until the late 20th century, to be described as a “religious” man in the American vernacular was equivalent to being called an upstanding member of the community. The plaudit had nothing to do with hewing to a particular doctrine.